Formerly known as the Rio Vista Bracero Reception Center, this newly recognized landmark used to be a processing center for large numbers of immigrants from Mexico.

In December 2023, former Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland designated an old farm in the city of Socorro, Texas, as a National Historic Landmark (NHL). On a list chock full of historic churches, former homes of presidents, and examples of grand architecture, the 14-acre farm with its dilapidated adobe-brick outbuildings stood out. Nonetheless, the National Park System and Haaland agreed that the property merited inclusion on the government’s official list of sites deemed historically significant.

That’s because Socorro’s Rio Vista Farm was formerly the Rio Vista Bracero Reception Center, a processing center through which tens of thousands of Mexican migrant farmworkers entered the U.S. in the mid-20th century as part of a temporary labor program. The arriving Mexican workers were known as braceros from the Spanish word for arm, brazo, roughly translating to “one who swings his arms.”

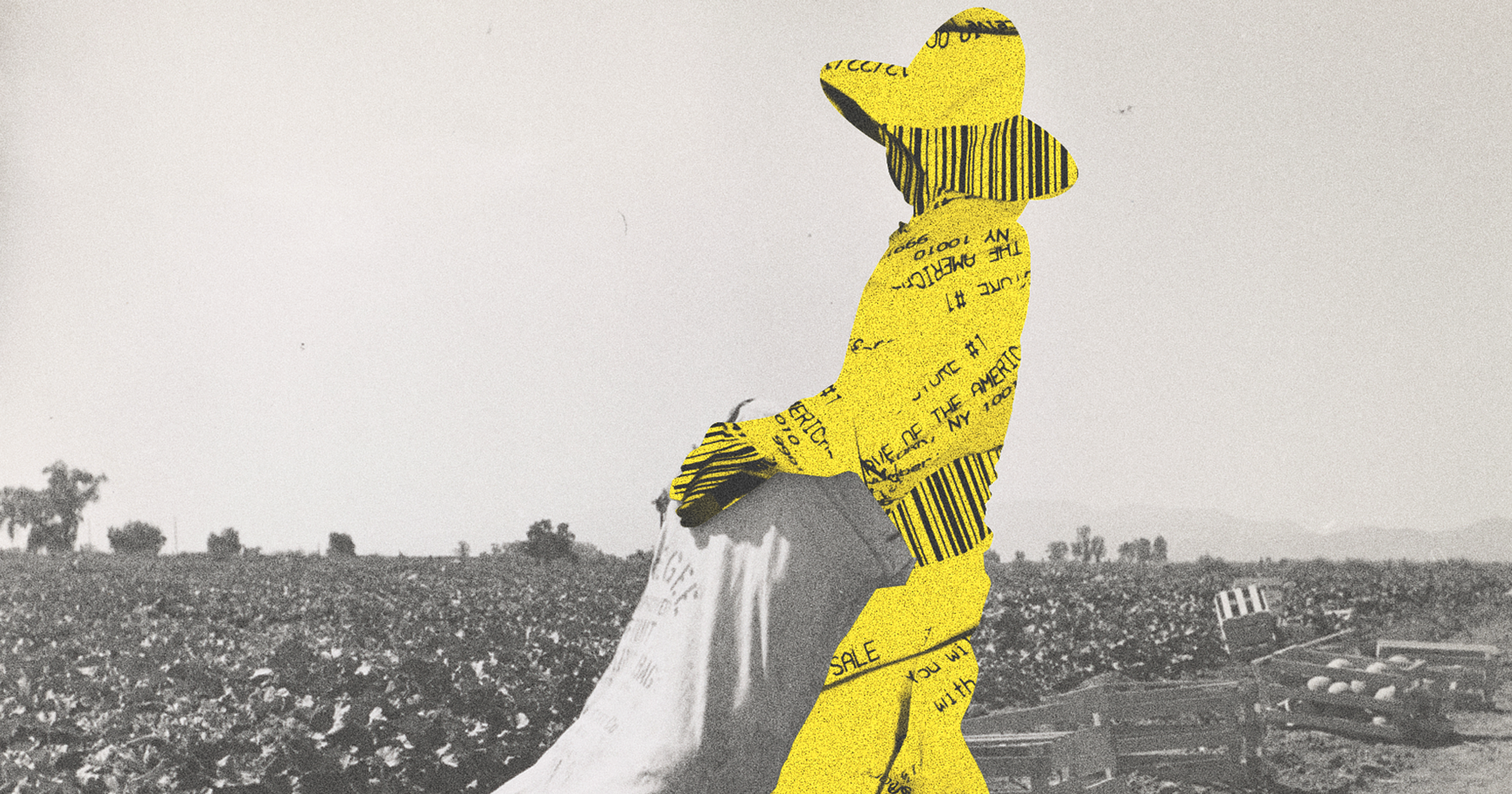

“One of the most incredible aspects about this story is that often in the United States, we think about food, but we don’t think about how our food is grown or who is enduring that extreme labor to bring us that food,” said Sehila Mota Casper, executive director of Latinos in Heritage Conservation (LHC). “The story behind Rio Vista is so important because of its association with agriculture and farm laborers.”

Rio Vista Farm’s journey to national recognition began in 2015, when Casper identified the site while working at the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The organization soon partnered with the City of Socorro and began working to secure funding for architectural studies, historical research, and interpretation, as well as critical stabilization and preservation work on the farm’s crumbling buildings.

Through archival work and interviews with former braceros, researchers pieced together Rio Vista Farm’s past and its role in the Bracero Program. The program, which ran from 1941 to 1964, was designed to recruit skilled agricultural laborers from Mexico to mitigate labor shortages in the United States resulting from American farmworkers enlisting during World War II and, later, the Korean War. Shortages were magnified during World War II when the government incarcerated tens of thousands of Japanese Americans, many of whom were farmworkers.

The young men who applied for the Bracero Program at intake stations across Mexico made significant sacrifices in pursuit of economic opportunities in the U.S. Many hoped that higher wages across the border would allow them to provide for those they left behind. “These are not just farmworkers, these are fathers [and] husbands who left behind their wives, their children, and also their culture and language,” explained Casper.

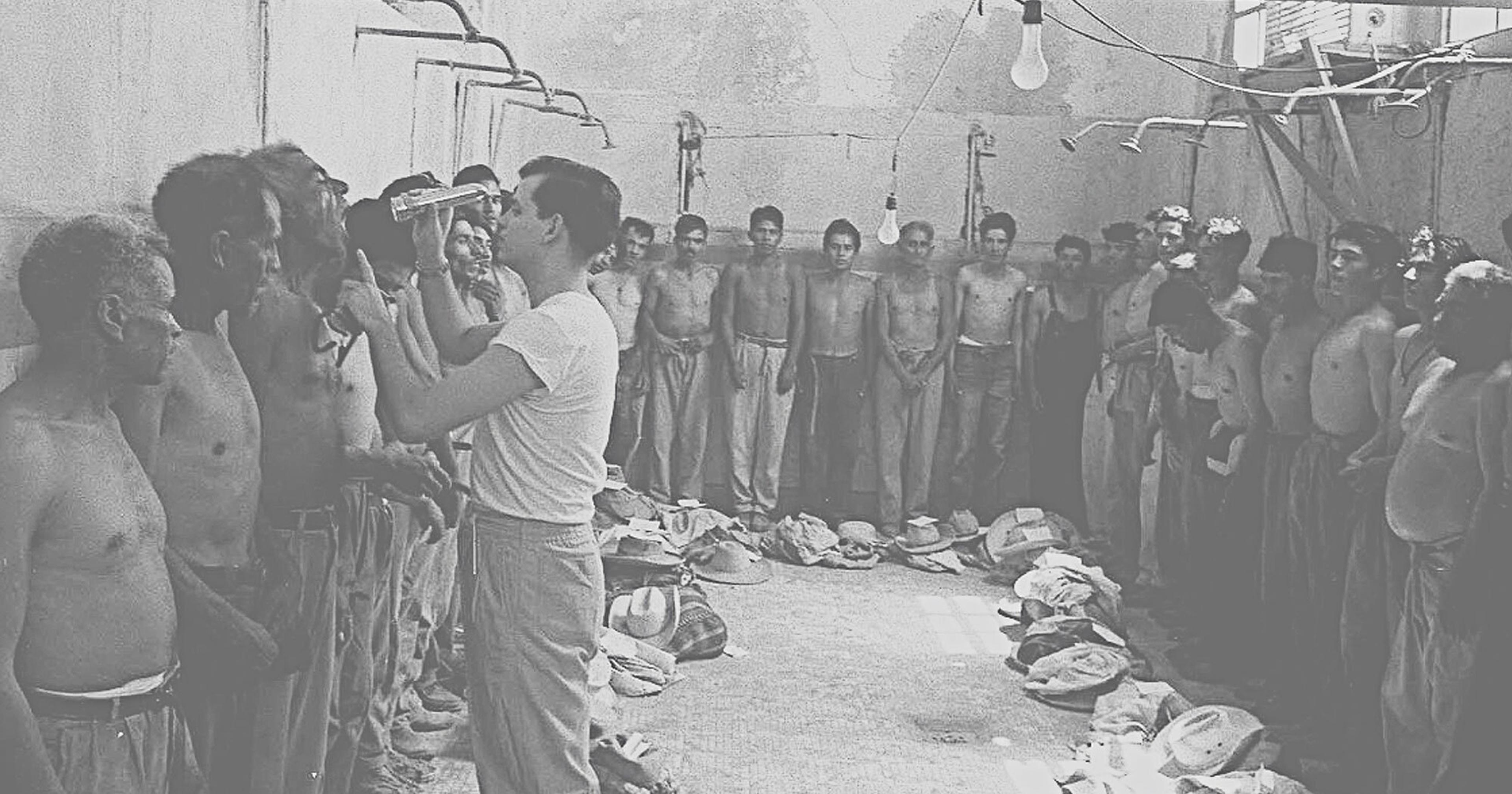

Applicants underwent humiliating medical and psychological examinations and delousing with dangerous chemicals such as DDT, before being invited to make the trip northward through Mexico and across the border, often in cargo trains without seats, windows, or water stops along the way. Mel Escobar, a former LHC graduate student fellow who researched bracero migration, said many “expressed pride in their role, despite enduring hardships such as racial tensions, low wages, humiliation, and navigating an unfamiliar culture.”

Federal official inspecting a bracero's teeth with a flashlight

·Library of Congress

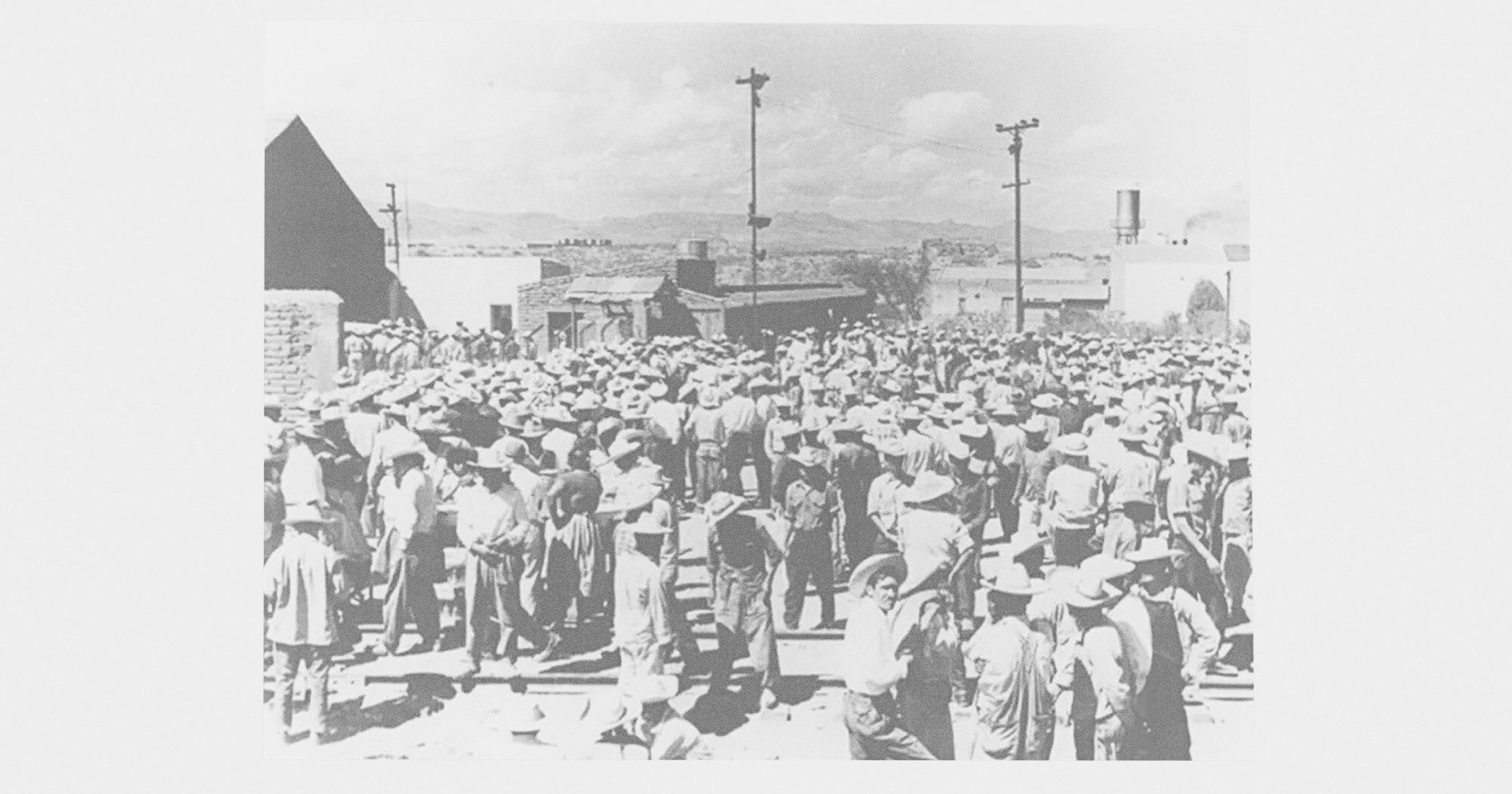

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the barracks on Socorro’s Rio Vista Farm served as dormitories, offices, and a mess hall to house and process the more than 80,000 braceros who passed through each year. It was one of five long-term bracero reception centers in California, Arizona, and Texas. At these sites, workers signed short-term contracts and boarded buses to farms in 30 participating states, going on to pick fruit in Michigan or trim tomato plants in California. Over the lifespan of the Bracero Program, more than 4.6 million contracts were issued.

After the Bracero Program ended in 1964, many of Rio Vista Farm’s buildings fell into disrepair, and its former use slipped from popular memory. According to Victor Reta, historic preservation officer at the City of Socorro, for decades before its recent revival, Rio Vista Farm had been “a mystery, like people knew that it was there, but didn’t really know what the barracks were for or anything of that nature.”

When Casper and Reta set out to preserve the old farm, 13 of the site’s remaining 18 buildings were empty and unmaintained. One that had been built for the Bracero Program was at risk of imminent collapse. The others had been repurposed as a community center and administrative offices for the City of Socorro.

“We talked about what the big dream was with the buildings, and we talked through what the community needed,” said Casper. Early on, the team made plans to nominate the site for NHL status. “We always knew the history was so significant that it should be a National Historic Landmark,” she said.

Braceros congregating at Rio Vista

·Library of Congress

Before Rio Vista Farm became an NHL in December 2023, the City of Socorro received grant funding from the Mellon Foundation to pursue another of the team’s early plans: establishing the nation’s first Bracero Museum and Cultural Center at the site. A project to rehabilitate and renovate one of the existing barracks for the museum is currently underway. Slated to open in 2026, the museum will feature an exhibition about the Bracero Program curated by historians from the University of Texas at El Paso.

While the museum has yet to open, other efforts to help the public connect with Rio Vista Farm have already launched, including an award-winning online exhibition about the Bracero Program created by LHC based on Escobar’s research. A ribbon-cutting in May 2024 to honor the site’s NHL designation and its being home to the nation’s first bilingual Spanish and English landmark plaque drew dozens of interested locals. “We’re seeing more and more visitation to the site as the story has become better known,” Reta said. “It’s been a really great project to connect people to their history.”

Casper said the task of honoring and educating the public about Rio Vista Farm’s past has begun to feel even more urgent since President Donald Trump took office again in January 2025. Trump has issued executive orders to change historical interpretation at National Park Service (NPS) sites in ways that obscure the contributions of working people and communities of color. Seemingly as part of these efforts, NPS removed Rio Vista Bracero Reception Center from its website earlier this year. “These actions send a chilling message about whose history is valued and whose can be thrown away,” wrote Casper in a press release.

The Trump Administration has also launched a crackdown on immigrants, sparking fear in farmworker communities nationwide. While the Bracero Program ended in 1964, the nation’s agricultural sector remains dependent on immigrant workers from Mexico. Almost two-thirds of crop workers interviewed as part of the Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 were born there. Another 6 percent were born elsewhere in Central America. Typically, 90 percent of those with H-2A visas, issued to foreign laborers to work agricultural jobs on a temporary basis, are from Mexico.

As Reta said, “The story that began at [Rio Vista Farm] and helped create America is still going on today.”

Editor’s note: The author of this piece writes for the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Saving Places.