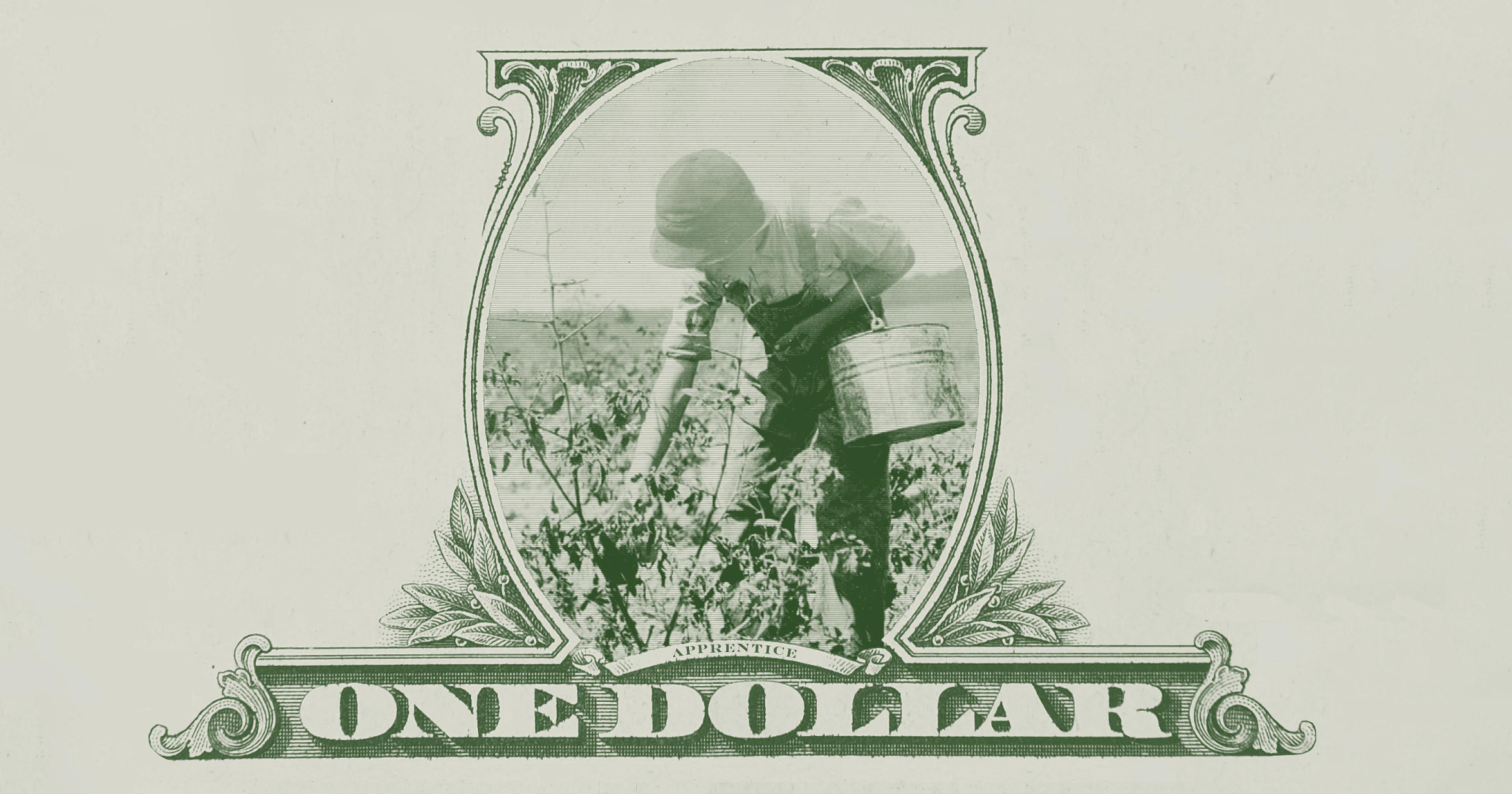

An emergent crop of labels aims to guarantee fair and humane farmworker treatment — but are they actually protecting workers as they claim they are?

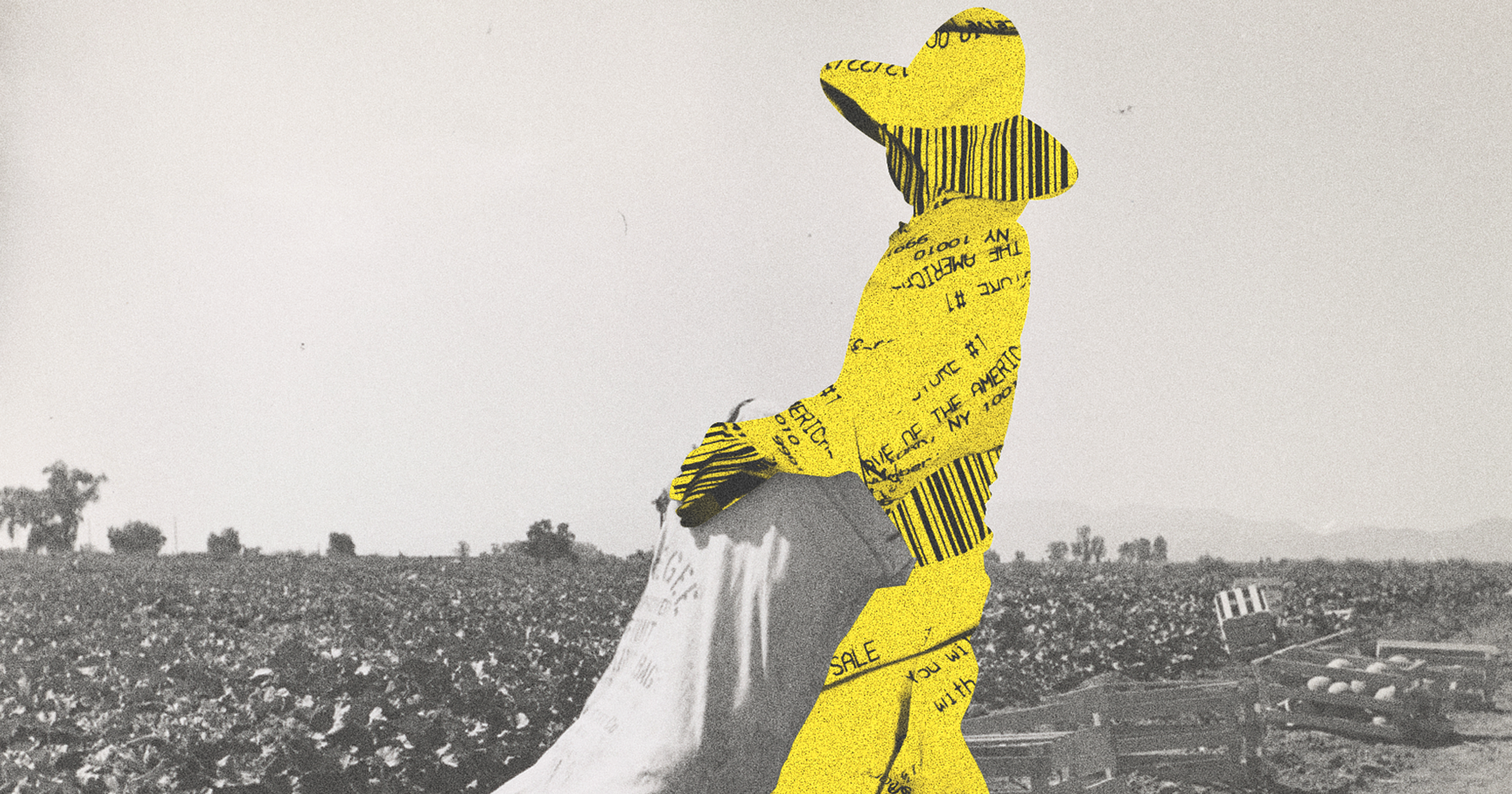

In 2017, two farmworkers hid in the trunk of a car to escape a forced labor camp in Pahokee, Florida.

The workers, who were brought to the United States on temporary agricultural visas, were coerced into insurmountable debts, isolated on labor camps fenced in by barbed wire, and threatened with arrest and deportation if they tried to leave. Five years after their escape, the farm labor contractor responsible for the abuses was sentenced to 118 months in prison and $175,000 in restitution by a federal judge.

The details of the case may sound shocking, but this sort of modern day-slavery is far too common in agriculture. Many of these abuse scenarios, however, fly under the radar — surveys by worker-based human rights organization Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) show pervasive coercion throughout the agriculture sector.

For consumers, it’s hard to know whether the produce they’re buying has been picked by workers who are subject to these kinds of labor abuses — the watermelons in the Pahokee case were sold on Walmart, Kroger, and Sam’s Club shelves.

Now, a growing slew of farmworker-friendly food labels aim to help grocery store customers navigate the issue, but they aren’t all created equally. Additionally, consumers are increasingly grappling with “compassion fatigue” — can more food labels actually grab their attention?

CIW’s Fair Food Label combines worker rights education with rigorous auditing, 24/7 complaint resolution, market-based enforcement mechanisms, and bonuses paid to farmworkers through a retailer premium. The Agricultural Justice Program’s (AJP) Food Justice Certified label ensures fair contracts for farmers, fair wages and working conditions for workers, and comprehensive environmental stewardship on the small- to mid-sized farms it certifies via third-party audits. The Equitable Food Initiative (EFI) Responsibly Grown, Farmworker Assured label focuses on social and food safety criteria and reduced pesticide use through certified auditors, as well as worker bonuses from a premium paid by retailers. Finally, Fair Trade USA’s Fair Trade certified label is meant to indicate fair working conditions, pricing, and eco-friendly cultivation.

Collectively these programs cover ample ground. CIW estimates it impacts 35,000 workers. EFI affects 60,000 workers under its active leadership teams. The AJP currently certifies four family and community farms and, in 2022, provided social justice funding to another five (three of which are BIPOC-led) to seek Food Justice Certification.

Though the reach of these programs is growing, currently consumers seem more focused on issues like pesticides, food safety, and animal welfare than fair treatment of workers.

According to a survey from EFI, 51% of consumers are concerned with unfair or poor working conditions for workers when purchasing fresh produce, while 64% are concerned with pesticide use and 63% worry about food recalls and illnesses. Meanwhile, a 2018 survey of 1,000 US consumers found 70% paid attention to animal welfare labels and 78% believed an objective third party should be ensuring farm animal welfare.

“I don’t think people in general know [about mistreatment of farmworkers] and I don’t think it’s high on their priority list of things to consider,” said Cheryl Queen, former Compass Group vice president of communication and corporate affairs, who helped usher agreements between CIW and Compass, one of the largest foodservice providers in the world. “But I think it’s a powerful story to tell and one that really resonates.”

An Effective Coalition

The Coalition has been at the frontlines of telling these tales since the early 1990s. Its Fair Food Program, which launched in 2011, was one of the earlier food justice schemes to forge partnerships among farmers, farmworkers, and retail food companies to ensure humane working conditions and better wages via legally binding agreements. To be part of CIW’s program, retailers must agree to only purchase produce from growers who have implemented its human rights-based Code of Conduct and pay an extra penny per pound for tomatoes (and varied prices for other crops) that gets passed down directly to workers in the form of a paycheck bonus. Since the program was implemented, it has paid $42 million in premiums to workers.

In 2014, CIW rolled out the Fair Food Label, which indicates that a certain crop was picked on partnered farms, with a large-scale marketing campaign in grocery stores like Whole Foods, Giant, and Stop & Shop, to help make consumers more aware of farmworker human rights abuses. Their labels now cover peppers in Florida, tomatoes in Tennessee, peaches and corn in Colorado, cut flowers in Virginia, California, South Africa, and Chile, and more. While the income bonus is a big part of the program, it also ensures its code of conduct is being followed by growers with audits — including more than 30,000 interviews with farmworkers in the fields — and a 24/7 complaint resolution line that addresses issues like sexual harassment, lack of heat protections, and stolen wages. The program has recovered $587,718 in stolen wages since its inception.

This complaint resolution hotline aims to eliminate retaliation from supervisors, covering everything from unpaid wages to sexual abuse and slavery; it has resolved more than 3,500 complaints to date. Every complaint is investigated by the Fair Food Standards Council human rights investigator. If it is a code violation — like 35% of the complaints filed between November 2011 and October 2020 were — the council works with the growers to find a resolution. If a grower is unwilling to address one of its three zero-tolerance code violations, which include forced labor, sexual assault, or child labor, it can no longer sell to the large-scale buyers (like Taco Bell, McDonald’s, and Trader Joes) which participate in the program.

Lupe Gonzalo, who worked in the fields for decades but now works directly for CIW, has seen first-hand what a difference the hotline and subsquent investigations have made, especially in terms of sexual harassment — one of the most common abuses in agriculture. A Human Rights Watch report found that nearly every one of the 47 female farmworkers interviewed had personally experienced sexual violence or harassment, or knew of another worker who had.

In one particularly memorable case, a supervisor at one of the farms where Gonzalo worked had been harassing female farmworkers for years. A worker reported the behavior to the Fair Food Standard Council, which brought it to the farm’s attention. If the farm chose to let the supervisor stay, it would lose its ability to sell to buyers in the Fair Food Program. After decades of harassment, the supervisor was finally fired.

This complaint resolution process paired with market-backed enforcement of standards is what CIW says makes its program more effective than others.

Murkier Standards

Fair World Project’s 2016 Justice in the Field report concluded that Fair Trade USA is a program “to approach with caution as [it has] some strong standards but weaknesses in enforcement and governance.”

The U.S.-focused labeling initiative for Fair Trade International, which independently certifies that producers and businesses have met internationally agreed upon social, economic, and environmental standards like living wages and safe working conditions, was not recommended in the report.

Equitable Food Initiative’s label, which is available in Costco and Whole Foods, received a recommendation with qualifications because “there is less emphasis on democratic organization of workers and on wages than some other programs.” Like CIW, EFI also charges a premium to retailers that gets returned to workers on participating farms. Since it began in 2015, $21 million in premiums have been collected through the program, of which $18.6 million has gone directly to workers.

Farmworker organizations including United Farm Workers were involved in the formation of EFI, along with growers and retailers, to create a multi-stakeholder approach to addressing food safety and fair working conditions. One of EFI’s main tenets is its extensively trained leadership teams, which are built to represent the diversity of the farm by including women, Indigenous workers, and contract laborers, to help create a safe outlet for workers to voice their concerns. Once a leadership team is in place on a farm, they work toward implementing EFI standards, before calling for a third-party audit of the operation.

To ensure farms continue living up to its standards, EFI performs yearly audits, 50% of which consist of farmworker interviews that are picked at random. The organization includes non-retaliation guidelines in its standards that call for additional worker and leadership team interviews along with document reviews if retaliation is suspected on a farm.

While Fair World Project’s report was mostly commendatory of EFI, it cited the lack of worker representatives present during interviews as an “area in need of urgent improvement.”

In another report published late last year, cultural anthropologist James Daria accused EFI and Fair Trade USA of “fairwashing”, due to allegations of involuntary overtime without overtime pay and fear of retaliation at Rancho Nuevo, a EFI-certified berry farm in Mexico that sells to Costco. One anonymous farmworker said, “The representatives of the EFI group are people close to the bosses or the foremen.”

EFI representatives said auditors increased the number of interviews at Rancho Nuevo after Daria’s report. In July 2022, 36 workers (7%) of the 512-person workforce were interviewed. In 2023, auditors spoke to 28 workers (4%) out of 699. The organization said it has found no evidence to back up Daria’s claims.

Peter O’Driscoll, EFI’s executive director, said the report is related to a recent interunion struggle between farmworker organizations in Baja California; he questions motives of the individuals interviewed, along with the overall findings. “EFI has never proposed to anybody that EFI certification is a guarantee of perfection,” said O’Driscoll. “But we try to establish a structure in our worker-manager leadership teams where workers can feel safe bringing their concerns.”

EFI’s stated goal is to build trust and create a collaborative environment between workers and management on the farm. Say there’s an issue — like a need for better access to water or shade in the fields, not enough toilet paper in the bathroom, or fallen produce creating slippery conditions — workers are advised to voice their concerns to EFI-trained leadership team members. If workers are not comfortable approaching those team members, they could go to someone at HR (or its equivalent) at any one of the 55 farms it certifies. If that doesn’t feel safe they can send a direct complaint to EFI.

A Third Way

The Agricultural Justice Project’s formal grievance process goes a step further by incorporating immigrant workers’ rights organization, Farmworkers’ Support Committee (CATA), into the fold. The New Jersey-based organization, which was founded in 1979, has a long history addressing issues like wage theft, discrimination, unfair firings, unsafe working conditions, and collective bargaining protections. When a formal complaint is filed with AJP, CATA representatives review it and assign investigators.

It is the only worker-led program other than CIW’s Fair Food that the Fair World Project highly recommended in its report. While it’s geared toward smaller family and community farms, some have hailed the certification as the “gold standard” in fair farmworker labels due to its strict environmental and health protections and its farmworker representatives that are involved in governance and on-farm monitoring and enforcement.

It’s hard to scale up when your standards are high, which is why so few farms have been certified by AJP. Its farms and food businesses must offer workman’s comp, disability, unemployment coverage, Social Security, unpaid sick leave, maternity/paternity leave, and high environmental standards — with USDA Organic certification at a minimum.

The Farmworker Association of Florida got involved with AJP shortly after it launched its worker-justice-focused certification and labeling back in 2011. “We believe in it because it also includes organic,” said Jeannie Economos, pesticide safety and environmental health project coordinator for the Farmworker Association of Florida. “We believe you can have the best fair labor standard label you want, but if they’re still using pesticides it’s still a big problem, because farmworkers are exposed to those pesticides.”

As many as 20,000 farmworkers are affected by acute pesticide poisoning (direct exposure resulting in immediate symptoms like headache, vomiting, or rash) in the United States each year. Numerous studies have shown that this exposure leads to higher rates of birth defects, developmental delays, leukemia, and brain cancer among farmworker children.

Obviously, there are numerous aspects of farm work that urgently need to be addressed. While there is still plenty of room to grow in terms of access, these worker-led programs have been paving the way for better labor conditions on participating farms. The two farmworkers that escaped enslavement in Pahokee did not work under any of these programs, all of which existed at the time of their exploitation.

As one UC Berkeley study found, these “market based initiatives can be a promising mechanism for improving farm labor conditions” when implemented well. That said, the most important component of ensuring their long-term success — and better working conditions for more North American farmworkers — will be getting consumers to understand what they mean and why they exist.

There’s not a lot of research documenting how much consumers care about the treatment of farmworkers when purchasing fresh products. But studies have shown that the more familiar consumers are with a certification, the more likely they are to trust the label.

Those involved in farmworker justice initiatives are hopeful that recent attention on farm laborers and the struggles they face will help guide grocery store shoppers to start considering social justice labels in their purchases. “I think that’s, dare I say, one good thing out of the pandemic, farmworkers became visible as essential workers,” said Economos. “Will it stay that way? We’ll have to see.”