A curious effect of climate change exacerbates extreme working conditions in cornfields.

If you’ve ever walked into a cornfield on a summer day and felt like you were entering a much stuffier world than the one you just left, you’ve probably experienced what is sometimes called “corn sweat.” And while that increased heat and humidity might result in perspiration beading up on your upper lip or rolling down your back, it’s not your sweat that gives the phenomenon its name — it’s the corn’s.

Corn sweat refers to the way these plants and the soil they’re planted in release moisture into the atmosphere. The scientific term for this is “evapotranspiration,” a combination of water evaporating from the ground surface and transpiring from the leaves of the plant itself.

While evapotranspiration is a normal part of plant growth, the increase in corn sweat is a muggy side effect of climate change — and it means hotter, more humid conditions in cornfields, which can have dangerous implications for farmers and workers.

Hazardous Harvests

The United States grows more corn than any other crop, which means it has an outsized effect on the agricultural industry. And while it doesn’t require as much labor as many other crops, humans are still involved in the harvest. That can be unfortunate for anyone working in those fields, given that it can feel 15 degrees hotter in a cornfield than outside it. According to professor Suat Irmak, head of agricultural and biological engineering at Penn State, if you’re working in a cornfield, “You are going to sweat a lot, and sometimes you might feel like it’s difficult to breathe because it’s so humid, so hot, and there’s a closed canopy.”

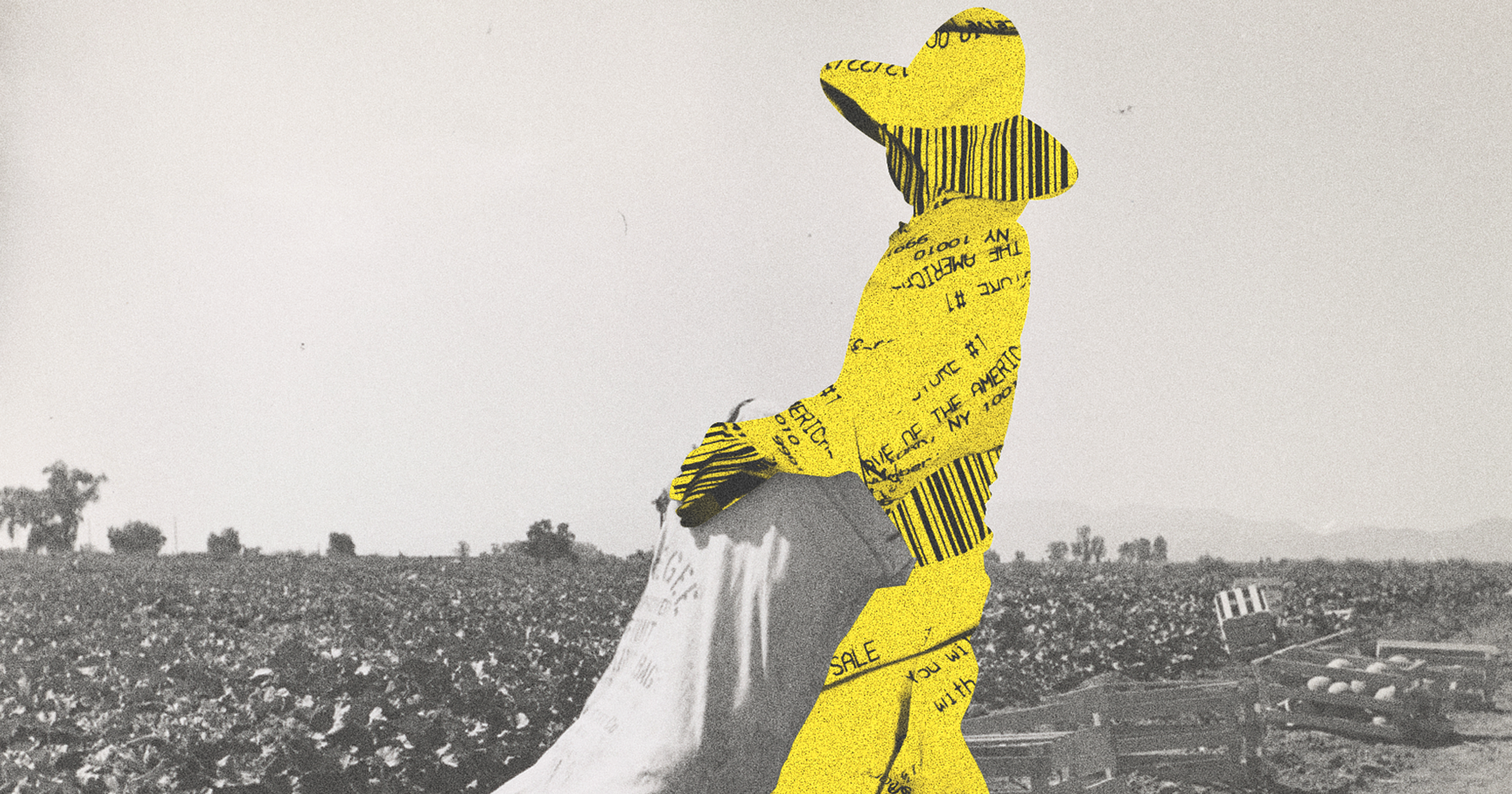

That may not have too big of an impact on a farmer driving a combine from an air-conditioned cab. But when maintenance, detasseling, hand-picking sweet corn, or other work requires spending time on the ground, that heat index difference can add up to significant — and potentially fatal — health risks for farm laborers.

That was the case for Cruz Urias Beltran, who died tragically from heat stroke while working in a Nebraska cornfield in 2018. Beltran is just one of hundreds of farmworkers who have died from heat-related issues in the U.S. over the last decade, where federal protections for farmworkers have lagged behind the rate at which growing seasons are getting hotter.

“As temperatures continue to rise, farmworkers are already working in the fields through record-breaking heat and in dangerous temperatures. This is a major factor in agriculture being one of the deadliest industries for workers in the United States today,” said Antonio De Loera-Brust, director of communications for the United Farm Workers (UFW).

“We have seen a notable increase in growing season temperatures across the U.S. In Illinois, all seasons have warmed over the last hundred years,” noted Illinois state climatologist Trenton Wayne Ford. “With that increase in temperature generally comes an increase in evaporation. Everything else being equal, under higher temperatures, the corn is going to sweat a little bit more.”

There are other non-climate factors contributing to increased corn sweat, too, like the fact that there’s been an increase in total acres planted — USDA estimates that U.S. farmers plant about 90 million acres of corn per year, the majority of which is used in livestock feed or ethanol production. More corn means more total corn sweat, regardless of temperature.

“In some cases, we’re talking about 3,000 to 4,000 gallons of water per acre that’s going into the air every day.”

Clearly, health-threatening heat isn’t a problem caused or perpetuated exclusively by corn sweat. Climate change means temperatures are rising, and warmer air holds onto more moisture, making it harder for peoples’ sweat to cool them off — regardless of whether there’s any corn around. Still, corn sweat can amplify other heat stress-causing factors.

“A cornfield provides an environment that may elevate heat index values more than where those heat index values are actually measured,” said Ford. In other words, there may be a significant difference between what a “producer sees on the [weather app on their] phone, and what they experience in the cornfields.”

Because heat indexes are often measured at airports, he noted, they don’t reflect how stifling a cornfield can be. “Every single leaf in existence” releases water vapor thanks to photosynthesis and transpiration, said Irmak. But corn’s high water output, and the overwhelming amount of it now being grown, have combined to give the crop a unique reputation in this regard.

“When corn is actively growing and at its peak, it’s probably taking out anywhere from about a quarter of an inch to maybe a third of an inch of water [from the ground] on a daily basis,” said Illinois state master naturalist and climate change specialist Duane Friend. “So it’s pumping a lot of moisture into the air. In some cases, we’re talking about 3,000 to 4,000 gallons of water per acre that’s going into the air every day.”

Sweat Solutions

Ultimately, evapotranspiration is a natural part of a corn plant’s life cycle, and not something that can — or should — be halted. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways to mitigate its negative repercussions for farmers and farm laborers.

Irmak suggests investing in soil moisture monitoring and evapotranspiration measurement technology when possible. This can help farmers minimize water usage — and even determine how far apart to place individual plants for maximum growing efficiency.

Though transpiration itself can’t necessarily be slowed, evaporation — the other half of the corn sweat equation — can be. Irmak recommends reducing tillage, and leaving corn stalks and residue to sit on the ground after the harvest is finished. The following spring, planting can happen without removing the debris. (The side benefit of this method, he noted, is that leaving the prior year’s residue in the field also helps with weed suppression.)

“When you don’t disturb the soil, and you maintain a great amount of residue on the soil surface, it minimizes evaporation losses,” he said.

Ultimately, corn sweat isn’t going anywhere.

When it comes to worker health and safety, “guaranteed access to shade, water, and breaks” are crucial, noted De Loera-Brust. “As farmworkers continue to do their essential work while on the frontline of climate change, we need strong, enforceable heat protections in the workplace.”

While UFW continues to fight for federal policy that will protect such rights for workers, growers can start integrating these practices on their own right away, regardless of federal law.

Part of what can help growers make responsible choices regarding worker safety — not to mention their own — is better heat index monitoring, which might start to shrink the gap between what the forecast says and what it actually feels like in the field. Friend and Ford are currently collaborating on initiatives that could help move that forward in Illinois.

“We’re hoping we can put in more evapotranspiration monitoring in the state, so that we can maybe give a few days advance notice in certain situations,” Friend said. “It’s mainly a matter of looking at what people are doing outdoors, and then being aware of what’s coming down the road and being prepared to take whatever action is necessary to protect themselves or to protect those workers.”

Ultimately, corn sweat isn’t going anywhere. But learning to manage it, and prioritize worker health and safety in the midst of it, is possible, said De Loera-Brust. “The workers who feed us deserve nothing less, regardless of the crop being planted, tended, or harvested.”