New research reveals that climate change is leading to more “rain-on-snow” events, which means more soil erosion, pollution, and toxic algal blooms.

A few years ago, an unusual weather event struck the Midwest: intense, late-winter rainfall. When heavy rains accumulated on snow, the subsequent early melt resulted in the Midwestern Floods of 2019, devastating 14 million people and crops across the heartland. The likely lost revenue from corn sales alone was more than $6 billion.

“I would say 50% of the farmers in our area will not recover from this,” Iowa grain farmer Dustin Sheldon told CNN at the time.

Though rain-on-snow used to be a relative rarity for Midwestern farmers, 2019’s floods are the result of an increasingly common winter weather event. Now, researchers at four state schools in different parts of the United States have collaborated on a new body of research around the increased winter run-off brought about by a warming climate. And what they found wasn’t just more water — there was also concentrated pollution at much higher levels than what results from more typical rainfall.

“We found that winter weather events are carrying a lot more nitrogen and phosphorus and other nutrients downstream than during the growing season,” said Carol Adair, associate professor in the environmental sciences program at University of Vermont, and one of the researchers working on the study.

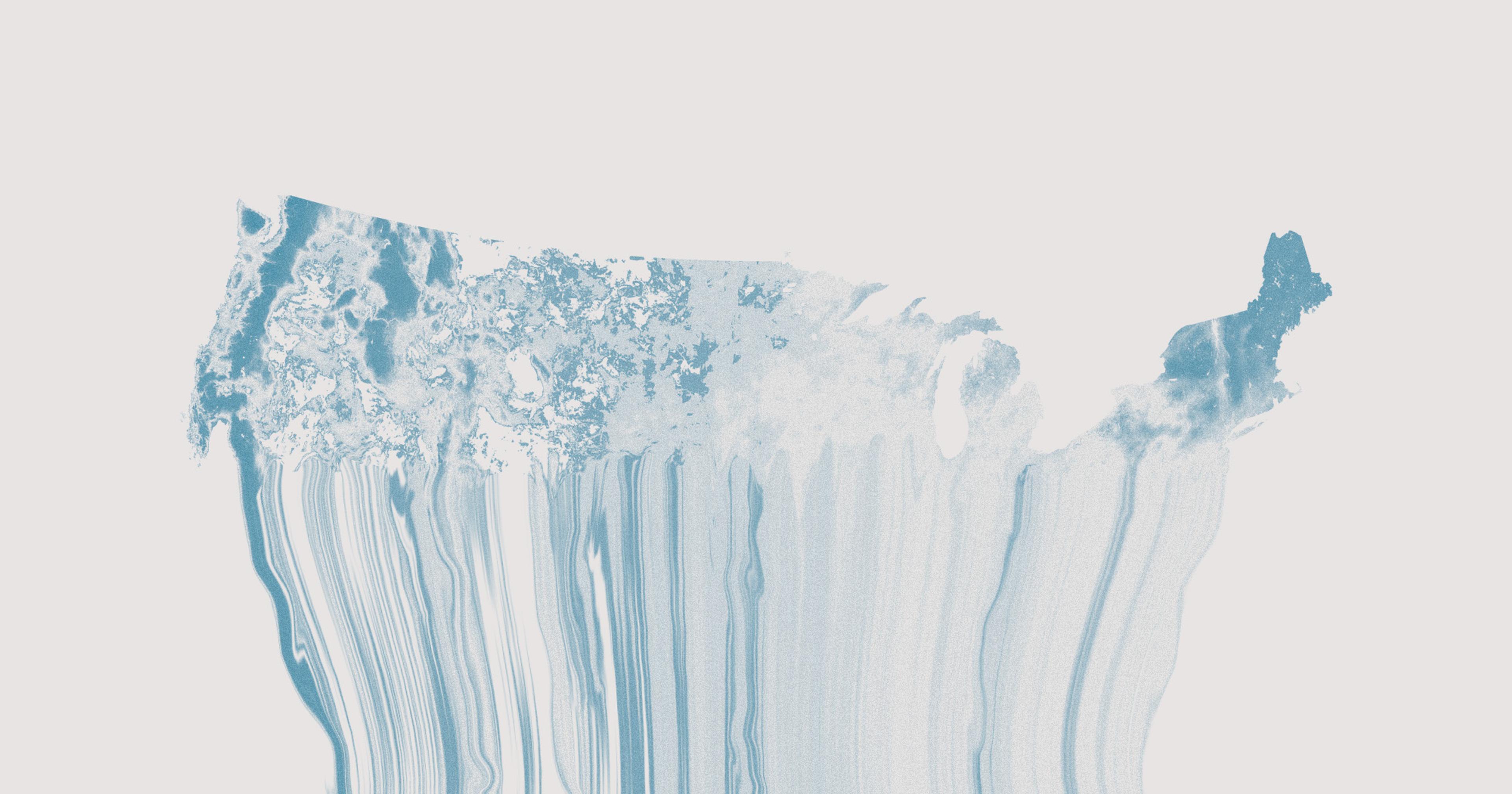

Nitrogen and phosphorus are, of course, key components commonly used in farm fertilizers. So Adair, along with researchers from University of Colorado, University of Kansas, and University of Michigan, used geospatial datasets to look at the rising impacts of rain-on-snow events on parts of the U.S. with higher concentrations of these nutrients, which tend to be agricultural areas. They found that winter runoff from farms is putting water supply at risk in more than 40 states.

The team’s research started in Vermont, where Adair said winter snowmelt and rainfall was occurring at much higher frequencies but that “no one was measuring it” — or its impacts. They went on to look at public data from those great Midwestern Floods of 2019, which confirmed a suspicion — that the flooded Mississippi River carried a level of nutrient pollution that was significantly higher than similar events during the growing season. This pollution was a major factor in the creation of the Gulf of Mexico’s eighth-largest dead zone on record.

Farmland fertilizer runoff has garnered headlines in recent years for its contributions to water issues like algal blooms, fish die-offs, and contaminated drinking water, which can be particularly harmful to infants. What’s novel about the new research is the seasonality and the scope: A full 40% of land across the contiguous United States is at risk of nutrient pollution from rain-on-snow events.

There are multiple potential reasons why winter rains may be more damaging than, say, April showers. Erin Seybold, an assistant scientist and hydrogeochemist at the University of Kansas and lead researcher on the study, said that vegetation — whether in the form of crops or wild plants — is obviously more prevalent during the warmer months. “Plants, as well as microorganisms or microbes in the soil, are important ‘sinks’ for nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil, retaining the nutrients that are now being transported downstream,” said Seybold.

Researchers believe that pinpointing this problem could help us develop greater monitoring in parts of the U.S. where rain-on-snow events and chemical concentrations are highest.

So, plants keep more nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil. They also happen to function as an actual physical barrier, helping to prevent moving water from running downstream so quickly that it causes damage.

When there’s nothing standing in its way, water doesn’t just carry nutrients with it; it also carries along loose dirt. Adair pointed out that these winter weather events speed up soil erosion — another agriculture issue of pressing concern. During typical winters of the past, snow insulated the soil through the season, keeping it stabilized and immobile. “If the soils freeze and thaw a lot that can cause more erosion and soil loss. Now we’re breaking up the soil … and everything gets very waterlogged,” said Adair. “Then runoff just carries the soil away.” This kind of soil erosion is harmful for natural ecosystems and farmers alike.

The study isn’t all bad news: The researchers believe that pinpointing this problem could help us develop greater monitoring in parts of the U.S. where rain-on-snow events and chemical concentrations are highest.

“If we can implement different land management practices that minimize negative effects and help to promote good water quality year round … that’s a really important area to direct resources and policies that can help farmers manage these impacts,” said Seybold. “Hopefully our research can encourage thinking about that and in collecting data to help inform those conversations.”

Those conversations can’t come too soon, as the patterns indicate winter weather events will continue to become more frequent in the coming years. “In addition to winters being the fastest warming season in the U.S., the longest cold snaps are becoming shorter, and the number of days with temperatures below 32°F is expected to continue to decline across the country,” according to a statement from the researchers. Not to mention that this new study was primarily focused on only one type of precipitation.

“I would say that our analysis is actually a fairly conservative estimate, because there are really three kinds of increasing winter weather events leading to dangerous runoff: there’s straight rainfall, snowmelt, and then rain-on-snow,” said Adair. “We were just looking at rain-on-snow, and the other two are going to increase over time throughout the U.S.”