Every year we read about numerous outbreaks of foodborne illness from leafy greens and other produce. The industry has gotten more vigilant, but significant challenges remain.

The crunchy green leaves on a head of romaine lettuce are a breeding ground for dangerous strains of E. coli that can make people sick. So is the tender skin of an onion, before it’s sliced and placed between the buns of a McDonald’s hamburger. From broccoli to carrots, Americans experience new outbreaks of tainted produce with a not-quite-comforting regularity.

Still, produce safety is only one priority among many for the farmers that produce these crops, who contend with financial challenges, hiring woes, and problems securing land, along with the day-to-day vagaries of weather and pests. That’s how it was for Joan Olson, who owns a 33-acre diversified vegetable farm with her husband Nick in Litchfield, Minnesota.

In 2018, she attended a training at the University of Minnesota that covered how to handle food after harvesting. Though she didn’t follow “bad practices” before, Olson learned how crops can become contaminated with bacteria like E. coli, and how simple fixes like having a firm cleaning schedule for their produce storage bins could make a big difference in keeping customers safe.

“I thought, woah, I want to make a lot of changes on our farm,” Olson said. “There were so many areas for improvement.”

Farmers like Olson are taking a proactive approach to keeping their products from harming the people who eat them. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimate that each year, 48 million people get sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die from foodborne illnesses. Last year, the number of hospitalizations and deaths from contaminated food doubled from the year before.

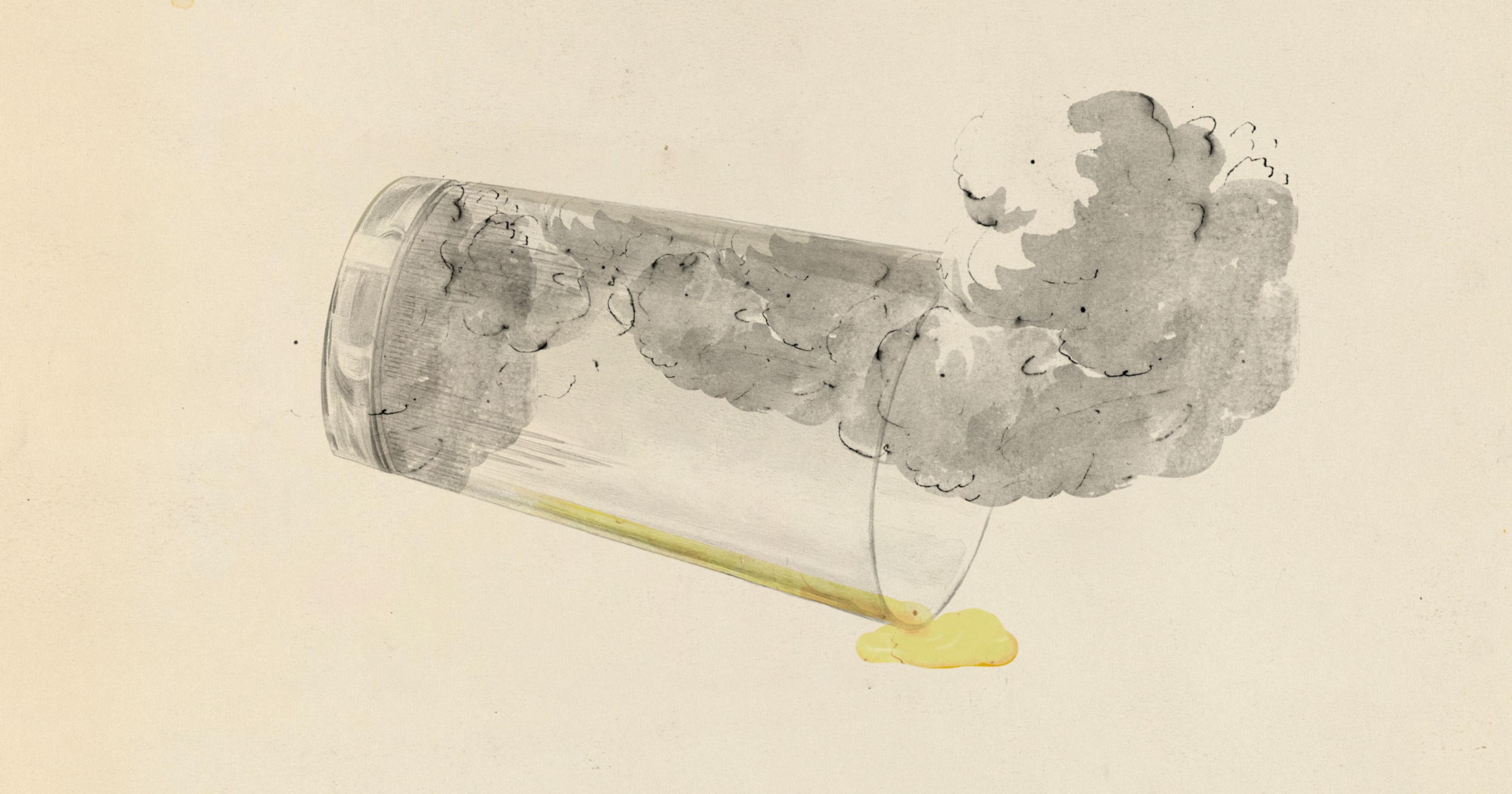

The main cause is poop — both animal and human. Manure runoff can contaminate water sources that are then used to irrigate crops, depositing bacteria like E. coli on produce. And agricultural workers can spread germs to the food they harvest by not washing their hands after using the bathroom.

Up until recently, growers large and small were trusted to deal with this problem on their own. “It’s a way to improve marketability,” said Don Stoeckel, environmental microbiologist and food safety educator with the Produce Safety Alliance, a partnership between Cornell University and two federal agencies. “Building consumer confidence starts with not having produce safety issues.”

But a series of E. coli outbreaks in the early 2000s — including one traced to spinach that sickened at least 276 people and caused three deaths in 2006 — led to calls for more stringent regulations, rather than voluntary guidelines. In 2010, Congress passed the Food Safety Modernization Act, which gave the federal Food & Drug Administration new powers to regulate the way foods are grown, harvested, and processed.

At first, the FDA required farmers to regularly test their “pre-harvest” water sources for bacteria and other sources of disease. This process, though, was considered overly burdensome by many growers, and it didn’t always work; irrigation water could be clear of contaminants at the point where it was sampled but then pick up new ones before reaching produce in the field. So last year, the agency made a change. Instead of making farmers submit samples of their water, they would instead have to conduct an annual assessment to identify any hazards, and come up with a plan to mitigate risks.

“American consumers by and large go to the grocery store expecting their produce is going to be safe, and they always have.”

That strategy, although more holistic, is also more confusing to many farmers, Stoeckel said. “Conceptually, this is a very good thing, because it sets up a system where a farm owner would understand the risk factors that might affect the quality of the water,” he said. “Better understanding leads to better outcomes, hypothetically.” But many farmers aren’t equipped to think through the complex ways contaminants could reach irrigation water and produce, Stoeckel added, making the process difficult and painful.

Farmers have to think about the location and nature of their water sources; a closed source like a well, for example, would be much less susceptible to contamination than an open one like a stream. They also have to identify possible hazards, like any nearby farms or concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) that could introduce fecal matter into their water supply (although some industry groups already require a buffer zone between CAFOs and leafy greens). And they should factor in the type of produce they grow; water might roll off of a watermelon but stick to the skin of a cantaloupe, while droplets can penetrate deep into a head of romaine lettuce but not a cabbage.

Growers that identify risks are obligated under the law to take steps to mitigate them, said Phillip Tocco, food safety educator with Michigan State University’s agricultural extension service. That means strategies like changing the way they irrigate, such as by using drip irrigation rather than sprinklers to minimize the amount of water that comes into contact with produce. Another strategy involves lengthening the time from irrigation to harvest, or the amount of time the food is stored before it’s packaged and sold, which allows bacteria in the water to die naturally.

Testing is still recommended, Tocco said, as a way to double-check that the measures farmers implement are working — but it shouldn’t be used as a pass/fail measure. To help them work through all of these complexities, he and Stoeckel, along with Annalisa Hultberg, a food safety educator from the University of Minnesota, came up with a risk prioritization tool that instructs growers on how to weigh the potential hazards to their water, and suggests ways to combat them. “There’s no such thing as zero risk,” Tocco said, but there are ways to get it relatively low.

Tools like this will be needed more and more as farms start to adjust to the new rules, said Elizabeth Bihn, director of Cornell’s Produce Safety Alliance (PSA); large operations have to start complying by April, while small and medium farms have a few more years to get ready. (Though with President Donald Trump slashing regulations and making deep cuts at the FDA, it remains to be seen how strictly these new standards will be enforced). The PSA hosts trainings for farmers all around the country, and since the new regulations were introduced last year, Bihn said she’s seen an outpouring of questions and requests from growers to help them understand the government’s expectations.

“It can be hard as a farmer to hear all the things you’re supposed to be doing and think, well how?”

Even without these regulations, though, Bihn said that the produce industry has vastly improved its food safety practices over the last few decades; farms now almost universally provide their workers with hand-washing stations, for example. Public health agencies have also gotten better at tracing the spread of foodborne illnesses and issuing recalls when needed — a factor that she said could make it seem like outbreaks are happening more frequently, when in reality we’re just detecting them more. And hearing about these events can lead consumers to put more pressure on the companies that produce their food, leading to further improvements.

“American consumers by and large go to the grocery store expecting their produce is going to be safe, and they always have,” Bihn said.

Growers like Olson are exempt from the new rules because they mainly sell directly to consumers through CSAs, and her water comes from a well, putting it at minimal risk of contamination; she tests regularly anyway out of caution. That came in handy one winter when a ruptured wellhead exposed the water to the elements, causing it to test positive for E. coli; Olson was able to catch the problem and sanitize her well before the water reached any crops.

Practices like testing and regular cleaning, she believes, not only improve food safety but also lead to better products that last longer on the shelf. And grants from federal and state agencies can offset any costs that come up, making it easier to adjust.

“It can be hard as a farmer to hear all the things you’re supposed to be doing and think, well how?” Olson said. “As a beginning grower, you have so many other things to think about. But when you convey the information with stories and share what other farms have done … people think, ‘I can go back and implement this on my farm.’”