Florida breeders are building spuds that can beat the heat, for an overlooked part of the tuber supply chain.

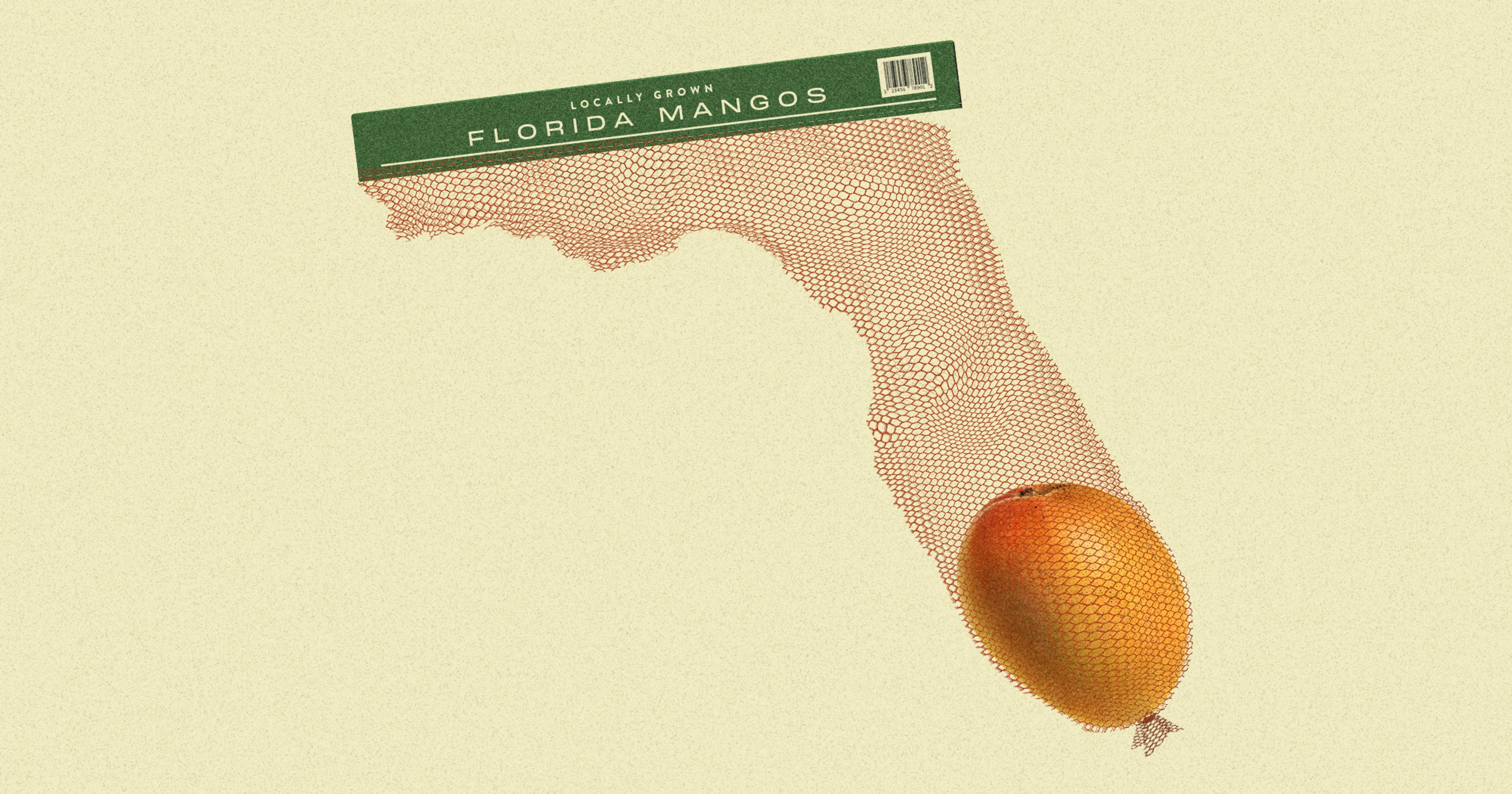

Only one community in the U.S. goes by the name of Spuds. As one might expect, it’s a potato-growing hotspot, nestled among nearly 20,000 tuber-bearing acres. Trains known as “Potato Specials” once hauled its produce to markets across the country — after heading past palm trees and ocean breezes.

While its name might suggest Idaho, Spuds is squarely Floridian, located about 15 miles from the Atlantic coast, 50 miles south of Jacksonville. For over 100 years, this corner of the Sunshine State has played a surprisingly large role in the domestic potato industry.

The Northeastern and Midwestern states that dominate U.S. potato production mostly plant during the spring and harvest in the fall, leaving a supply gap for the early months of the year. Florida producers are happy to fill that need by harvesting spuds planted over their subtropical winter. From about 2 percent of the country’s potato acreage, they meet roughly a third of U.S. demand from February through June. It’s a lucrative market: Florida potatoes sold at a premium of more than 60 percent over the U.S. average in 2023.

Yet Floridian farmers are working to fill that niche with a plant that was originally domesticated under very different circumstances — the highlands of the Andes Mountains in Peru and Bolivia. Those climatic roots make potatoes a natural fit for places like Idaho, and efforts to improve the crop by breeding have focused on varieties for cooler, drier conditions.

A recently launched effort at the University of Florida is working to make sure these potato growers aren’t stuck with the proverbial crumbs at the bottom of the chip bag. In 2021, researchers at the UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences established the state’s first public breeding program specifically aimed at developing Florida-adapted tubers.

Marcio Resende, who runs the program together with UF colleagues Lincoln Zotarelli and Leo Hoffmann, noted that the university has been evaluating potato varieties developed elsewhere and advising growers about which perform best in Florida since the 1930s. But the cultivars that went into their Southern trial fields, he said, inevitably reflected the biases of Northern breeding programs.

“Breeders would first select varieties that were good for them, then those best selections would come to Florida,” Resende explained. “The risk is that, if something wasn’t as good in Maine or Michigan, potentially it would never come to Florida, and maybe we would lose the ability to screen more diversity and identify materials that could be better here.”

Florida’s main red potato variety, Red LaSoda, was originally developed in 1953; its most popular chipping potato, Atlantic, was released in 1978. These older genetics, not optimized for the Florida environment, contribute to per-acre potato yields that trail the national average by about a third.

“We usually just get the leftovers. We find something that’ll work here, and that’s it,”

Now, the Florida breeders are making new potato varieties of their own, creating roughly 15,000 new genetic combinations every year and growing them over 15 acres in a combination of greenhouses, small plots, and replicated trials. Most of the crosses start between previously improved cultivars, which earlier generations of breeders have selected for characteristics like yield, disease resistance, and specific gravity (a measure of the tuber’s dry matter, particularly important for potato chip makers).

There’s still a lot of untapped potential in those varieties. Potatoes are a tetraploid crop, meaning they have four copies of each chromosome instead of the usual two — and thus more chances for genetic variation that a breeder can tease apart and recombine in useful ways.

Resende recalls a rainbow of potatoes growing from the field in seemingly every shade between crimson and white. “The amount of variability that you see in the progeny is exemplified in the colors, but you see it for everything: shape, size, yield. It’s just amazing,” he said.

Such diversity can be challenging to work with, admitted Resende, because breeders must be mindful of variation in more traits than usual when selecting potatoes. But it also provides more opportunities for a unique combination of genetics to come together that will meet Florida’s unique demands.

Resende said growers want early-maturing varieties that can provide respectable tubers before the state’s summer rains make harvesting difficult. Heat tolerance is also critical, especially for chip potatoes, which often develop a browning defect called internal heat necrosis that makes them unsuitable for processing.

Given the potato’s mountain origins, said Jiwan Palta, heat tolerance generally hasn’t been a breeding focus. He’s a professor emeritus of plant and agroecosystem sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, with over 40 years of experience researching stress in potatoes and other crops.

“I always tell my students that potatoes love what we like: about 70 degrees Fahrenheit is the ideal temperature.”

“I always tell my students that potatoes love what we like: About 70 degrees Fahrenheit is the ideal temperature,” Palta said. “Once you get above that, they can survive for a short time, but they don’t do well in terms of production.”

Yet breeders are paying more attention to heat in potatoes, Palta continued, as climate change ratchets up temperatures even in historically cooler growing areas. He and others have identified traits, such as antioxidant production and the ability to use calcium, that protect against heat stress. And there are reasons to be hopeful that the crop has the needed diversity: Some wild potatoes that grow near the coasts of Argentina and Brazil, he pointed out, can keep growing strong under 100-degree conditions.

The genetic complexity of heat tolerance, added Palta, means that there’s likely no quick-fix molecular engineering option for the trait. He believes potato breeders will be best served by a deliberate, traditional program of crossing and selection, as Resende and his colleagues are doing.

The Florida team estimates that their program’s first variety will be ready for release in seven to 10 years. Resende said that, beyond the state, that new potato is likely to find an eager audience across the Southeast and possibly beyond if heat and humidity become greater problems throughout the crop’s range.

Among the growers awaiting the program’s results is Daniel Corey of DeLee Produce, just down the road from Spuds in St. Augustine. Corey said he raises about 400 acres of red, yellow, and white potatoes for fresh consumption, selling direct to large grocery chains like Publix, Aldi, and Costco that want a premium product in otherwise lean months.

Potatoes better adapted to Florida, he believes, will translate directly into an economic boost for farms like his.

“We usually just get the leftovers. We find something that’ll work here, and that’s it,” Corey said of existing varieties. “Now, we’re focusing time and effort right into breeding for Southeast growers, so I think it’s going to be great.”