Unhealthy sagebrush habitats threaten ranching and endangered species, while fueling more frequent and intense wildfires. Incarcerated people in five Western states are helping restore these habitats.

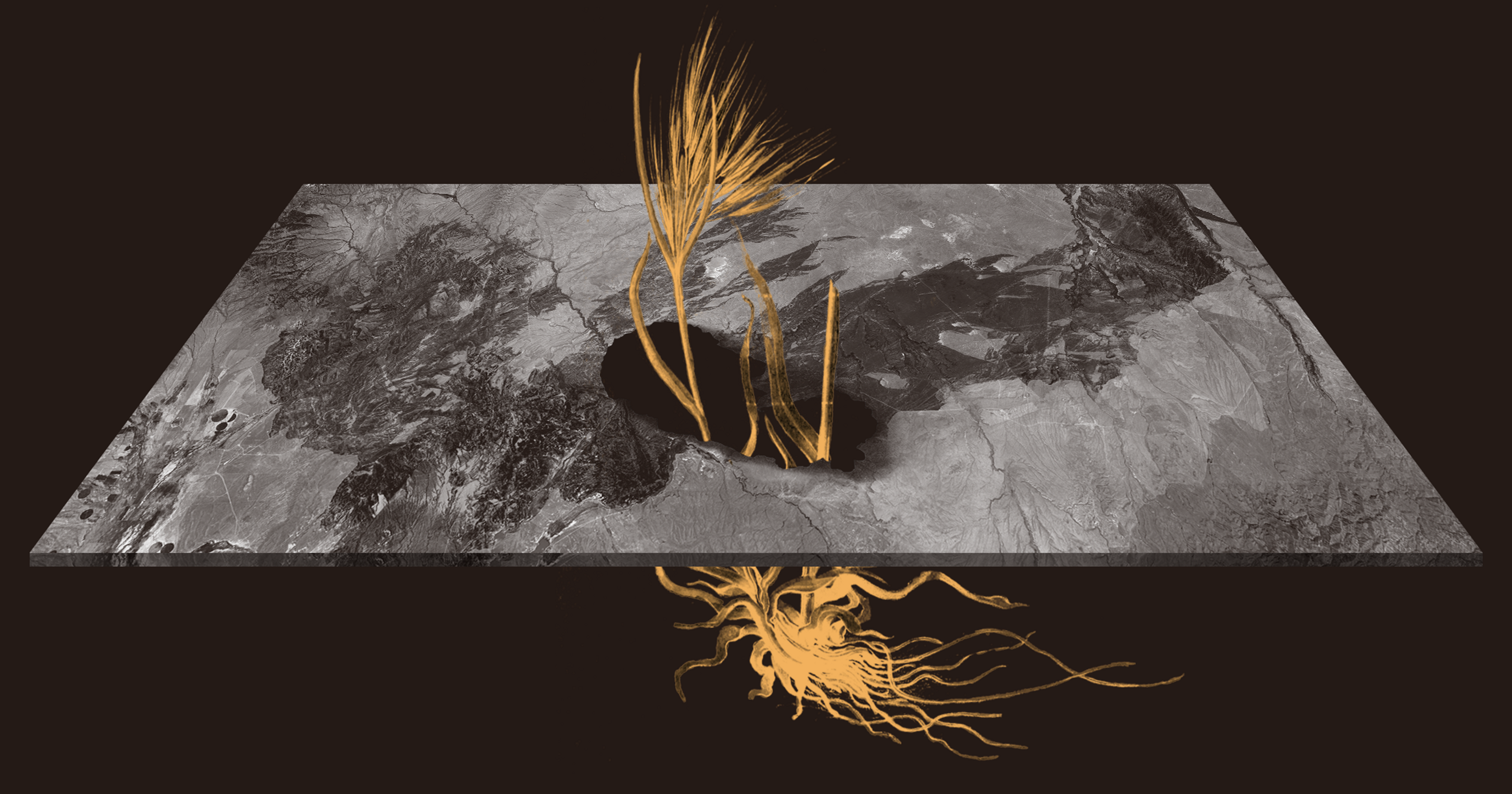

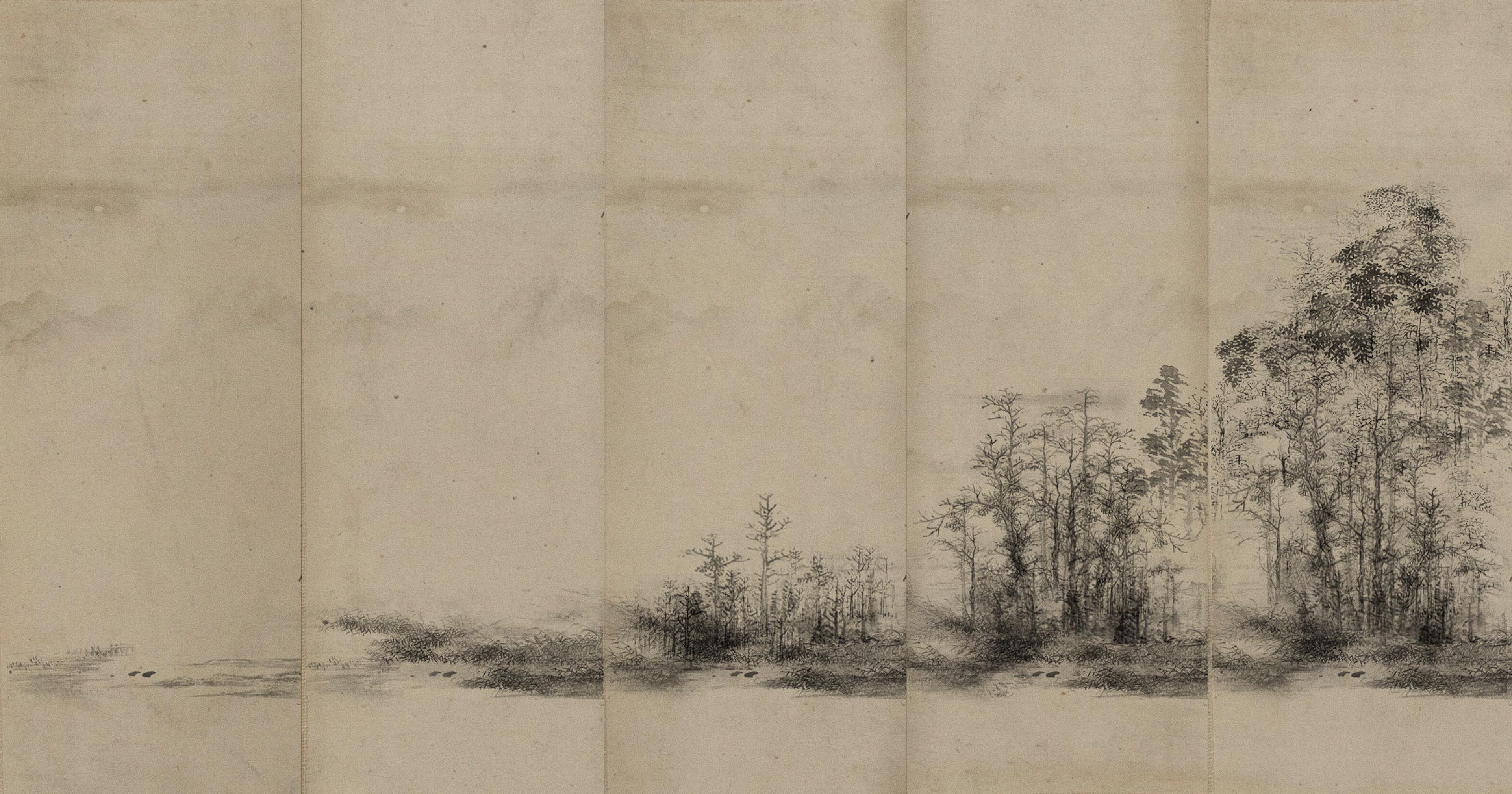

Restoring sagebrush ecosystems across the Great Basin is a critical tool for curbing the spread of wildfire-prone invasive grasses, protecting threatened species, and supporting grazing animals like cattle and sheep that have long been emblems of the American West.

“Sagebrush is an ecological and cultural keystone species,” said Karen Hall, ecological education program director with the Institute for Applied Ecology. “If we lost all of the sagebrush habitat in the world today, ecosystems and human systems wouldn’t function — it would mean the loss of hundreds of species and the loss of livelihoods for people in those habitats and beyond.”

To supplement what’s been lacking in the commercial native seed market, a recent crop of prison projects have stepped in to offer unique ecosystem restoration solutions. Hundreds of incarcerated people across Western rangelands are growing difficult-to-cultivate sagebrush plugs that are improving the ecosystem while building valuable skills.

The Sagebrush in Prisons Project is active in nine prisons across five different states that span the Great Basin. Incarcerated crew members sprout local sagebrush varieties from seed and care for the delicate plants by watering, weeding, thinning, and fertilizing throughout the spring and summer months. Come fall, those seedlings are boxed up and sent to various Bureau of Land Management restoration sites. These areas were previously scorched by massive wildfires, including the Martin Fire in Nevada, Paisley Fire in Oregon, Gas Hills in Wyoming, and Soda Fire along the Idaho-Oregon border.

The issue of restoring these rangelands is so critical, it’s brought together a diverse coalition of interests — ranchers, environmentalists, hunters, governmental agencies, and others — who don’t typically see eye-to-eye on public land issues.

Working together to sow this aromatic shrub across the sagebrush steppe seems like an easy win, but there’s just one major hitch. Finding the seeds and plugs to replant has been extremely difficult. That’s where these prison projects come in.

“I’ve never been more excited to be part of something more far reaching than myself than when I volunteered to participate in this sagebrush project,” wrote Lynn Huffman, a sagebrush program participant at Lovelock Correctional Facility in Nevada, in an open letter. “I am truly grateful to those beyond the prison for bringing this stage of the project to the inside.”

After wildfires, the lack of native flora opens the door to invasive cheatgrass and other pernicious, fast-growing weeds that quickly fill in the vast sea of bare land left in the wake of these infernos. These fine, flashy fuels dry out much earlier in the wildfire season than native sagebrush, helping to spur more intense fires more often, creating a vicious cycle that leads to even more loss of sagebrush and healthy rangelands.

“It’s not a sea of sagebrush anymore. We are losing it. It is going away and it’s really depressing.”

“It’s not a sea of sagebrush anymore. We are losing it. It is going away and it’s really depressing,” Caleb McAdoo, a biologist with the Nevada Department of Wildlife, told NPR.

The sagebrush seedlings reared in these prison programs help the ecosystem to recover more quickly after the blazes, thereby preventing (or at least limiting) future wildfires. These young plants also help to provide critical habitat for threatened sage-grouse, an umbrella species that acts a barometer for the health of the rangelands. Ensuring the health of sagebrush rangelands is important for local ranchers, too, because the plant increases water retention in the soil, protects grasses and forbs from overgrazing, and helps to maintain forage production for cattle and sheep.

This is why ranchers across the sagebrush steppe have been increasingly working on conservation measures to preserve the precious plant and overall ecosystem of their grazing lands. “It doesn’t happen overnight,” said cattleman John O’Keefe of Adel, Oregon, at a public meeting several years back. “But [ranchers] see what happens, you know — if they look over the fence and see these junipers going away and seeing this rangeland opened up — and the benefits you get from doing these things, and it kind of sells itself.”

There are multiple species of sagebrush, so each of the prisons working on this project cultivates varieties that are indigenous to the specific microregion. For example, at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, the program focuses on growing sagebrush from Central Washington that’s adapted to an elevation of somewhere between 1,000 and 3,000 feet.

Last year, incarcerated program technicians and SPP staff grew 35,000 plugs that have been sown densely in the area that surrounds Ellensburg. The hope is that these plants will spread out to expand its habitat and curb the spread of cheatgrass. This year, the organization is on track to produce around 50,000 plants for the region. “The state is focusing on this range and a couple others because of frequent wildfires,” said Carl Elliott, conservation nursery manager for Sustainability in Prisons Project, which partners with the Insititute for Applied Ecology on the Sagebrush in Prisons Project.

Across the West, the Institute for Applied Ecology’s programs have been growing roughly half a million sagebrush plugs per year, adding up to around 3.5 million since its inception. The benefits go far beyond ecosystem restoration.

“They have real knowledge to be able to work with plants in the future.”

The crew members who are involved in these programs get paid for their work. It’s a paltry fee — $1 per hour in Washington — that’s dictated according to state guidelines. But these sorts of voluntary programs are not about cheap labor, say the people involved. The organizations running them want to bring the benefits of education, training, and other positive impacts. These benefits include reducing idleness, which has been associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety, and giving them the ability to make decisions in an environment that strips away basic freedoms. Having some sense of agency in prison has been shown to boost self-esteem and improve psychological outcomes. “I hear they come out to work on our crews because it’s a space where they can have some autonomy,” said Hall. “They live in an environment where all variables are controlled.”

Studies have also shown that correctional education programs improve outcomes for incarcerated people once they are released. A report by RAND Corporation found that incarcerated individuals who participate in vocational skills and education training had a 43% lower chance of recidivating than those who did not.

Plus, the crew members involved in the Washington state efforts, which are overseen by The Evergreen State College’s Sustainability in Prisons Project, can receive up to 18 college credits at no expense to the student. The Institute for Applied Ecology is currently working toward establishing college credits for its crew members across the states (outside of Washington) in which it offers programs.

This sort of training could potentially lead to careers in farming or nursery work post-release — if formerly incarcerated people are actually given the chance. “Our students receive extensive nursery education and training like integrated pest management, proper watering and fertilizing, and introduction to ecology of shrub steppe ecosystems,” said Kelli Bush, co-director of the Sustainability in Prisons Project. “Ecological horticulture is the basis, so they have real knowledge to be able to work with plants in the future.”

So far these organizations haven’t had much opportunity to maintain contact with sagebrush crew members after their release (though they have been able to stay in touch with crew members from some of their other ecological restoration programs). Representatives from both organizations say they’re working toward making that easier. But Hall recently learned that one 82-year-old formerly incarcerated individual who worked at Warner Creek Correctional Facility’s program went on to start a sagebrush farm after completing his sentence.

Stories like that are a win for these ecosystem restoration efforts and all the people who have dedicated their lives to these programs. “We don’t expect that all crew members will be released from prison and then walk into a job in the horticulture industry,” said Hall. “But when it happens, it feels good.”