Nearly 20% of U.S. farms have no access to the internet, limiting their ability to embrace precision agriculture, boost crop yields, and implement more sustainable practices.

In Conrad, Montana, grain farmer Ken Johnson relies on a range of technology-driven equipment to oversee operations on his 4,500-acre farm — much of which relies on a steady connection to the internet.

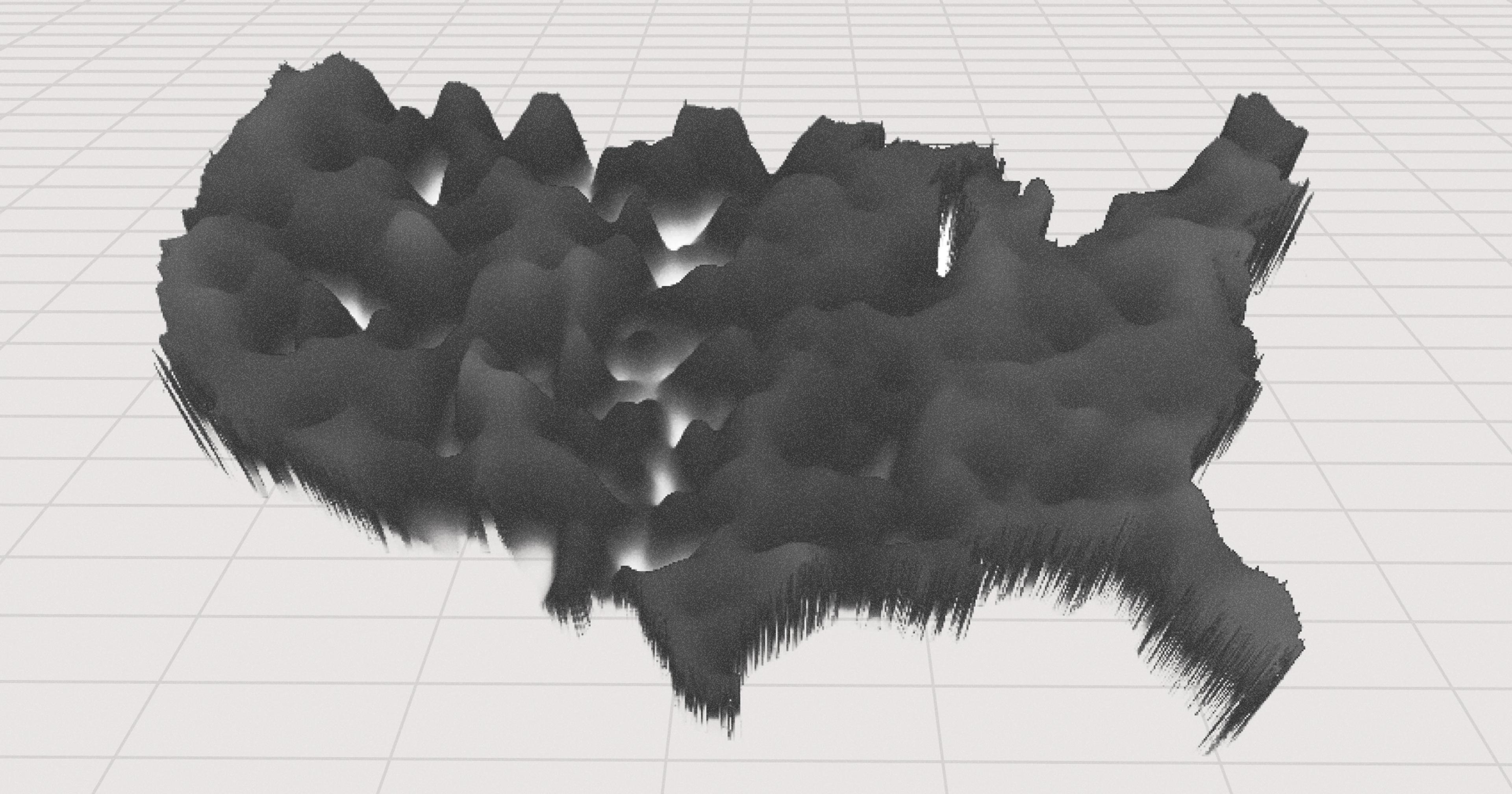

Located 23 miles away from what he calls “a huge town of 2,600,” Johnson is lucky to have fiber-optic internet service in his home. But not every farm in the area — or across the country — is served as well. In fact, Montana has some of the country’s poorest internet in both coverage — 69.2% — and download speed — 20.3 megabits per second (Mbps). (For comparison, the state with the best internet, New Jersey, clocks speeds of 52.0 Mbps.) Other low-ranking states include Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma and Wyoming — a fair representation of America’s rural broadband internet problem.

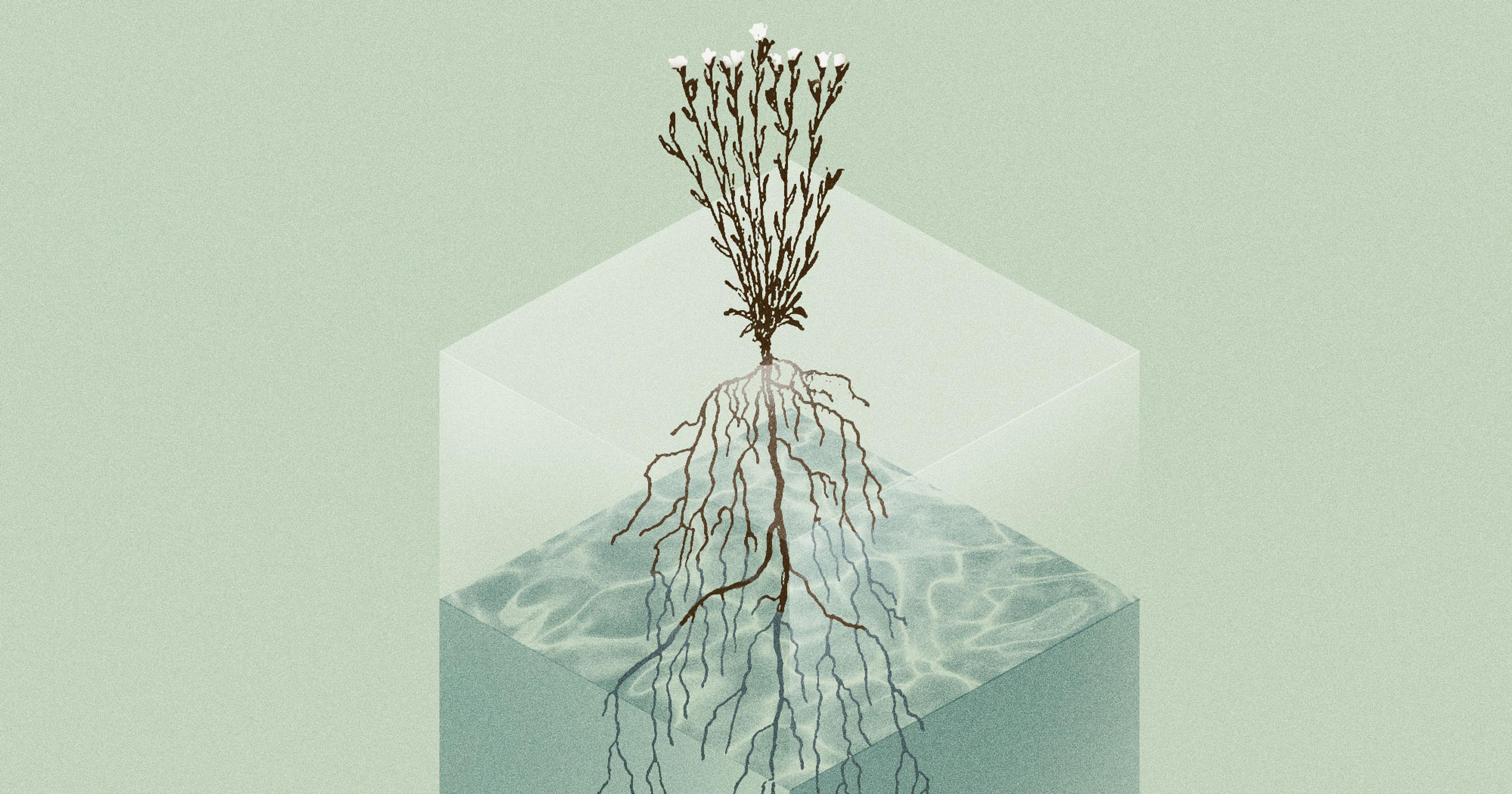

Lack of reliable internet access has a trickle-down effect on farmers. Without connectivity, producers can’t conduct basic tasks that come with running a modern business. In an increasingly online world, producers rely on the ability to search online for the best input prices to help boost profit margins, shop for replacement parts for their equipment, apply for funding, and run platforms that rely on direct-to-consumer (DTC) marketing. In the field, improved connectivity at high-speed thresholds has been shown to correlate with higher crop yields — but that all depends on the robust upload and download speeds that modern farm equipment relies on to function efficiently.

“Things are moving more and more towards technology to drive the decisions that we make. The more data the better,” said Johnson, referencing everything from soil sensors to smart tractors to online accounting systems. “Everything is moving to the cloud, and you need internet access for that.”

According to the most recent Farm Computer Usage and Ownership report, published every other year by the USDA, 18% of farms have no access to the internet at all. Further, only half of internet-connected farmers access broadband (DSL, cable, fiber optic) to connect to the internet, with others relying on cellular or satellite connections to conduct their operations.

And as innovations continue to sprout up in the agricultural sector — autonomous tractors, laser-weeding robots, wireless temperature and soil moisture probes — connectivity is more important than ever. The rise of precision agriculture has the potential to boost yields and profit margins, while lessening reliance on fertilizer and other inputs, among other benefits. But none of that is possible if farmers can’t access the new equipment’s programs through the internet.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines broadband as having download speeds of a minimum of 25 Mbps and upload speeds of at least 3 Mbps, and can include everything from WiFi and satellite to fiber-optic cables. As the industry shifts to autonomous machinery, it’s estimated that farmers will need 300 Mbps download and upload speeds for the technology to function as intended.

In agriculture, producers are generally less concerned with download speeds; the speed of uploading data to the cloud is more vital. A farmer might have many sensors and devices installed across their fields, all of which need to transmit the real-time aggregated data to the cloud. That’s a lot of information moving in one direction.

A host of programs and initiatives aimed at improving rural America’s internet deficits have launched in recent years. Passed in 2021, President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) dedicated $65 billion for broadband funding and other activities that close the digital divide through four programs. This included funding for the Internet for All initiative, which allocated $45 billion into providing affordable and reliable high-speed internet for everyone in America by 2030. The monies were provided to states and tribal communities, which were left to determine how to allocate the funding.

Earlier this year, the Biden-Harris administration announced an additional $502 million in loans and grants to bring high-speed internet development to rural and remote areas across 20 states, including to tribal lands and people in socially vulnerable communities. Since its inception in 2018, the USDA’s ReConnect Program has also provided nearly $2 billion in funding for the construction and improvement of broadband service in rural areas.

“Some of the the underserved areas don’t get the money because [internet providers are not going to make any money there for a very long period of time.”

But some say those funds haven’t been distributed fairly. “Part of the problem we see with rural broadband is a lot of times they’ll throw money at a state. And they’ll service the already serviced areas … whereas some of the the underserved areas don’t get the money because [internet providers] are not going to make any money there for a very long period of time,” said Johnson, who’s also the former Montana Farm Bureau District 8 director. “So it’s kind of frustrating to watch the really underserved areas not get the money that should have been spent there.”

In Indiana, Dennis Buckmaster, hobby farmer and professor in agricultural and biological engineering at Purdue University, is also frustrated by the rollout of broadband funding programs. “[The lack of connectivity] needs to be solved; it shouldn’t be ignored. The funding shouldn’t still go to places that already have [internet] while there’s still a place that doesn’t have anything,” said Buckmaster, who spoke to me over a Zoom call using a WiFi hotspot, which requires a personal cell phone signal booster to amplify an otherwise weak signal, because he doesn’t get internet access in his home.

In order to determine which areas are unserved or underserved, and thus who receives funding, a lot of these programs rely on detailed broadband maps provided by the FCC, the latest update of which was released on November 18.

However, not everybody is pleased with the maps, which provide a picture of where broadband internet is available based on fixed locations, such as homes and businesses, but overlook the acres and acres of fields in which farmers rely on connectivity to conduct and improve their work.

The importance of expanding connectivity “goes beyond bingeing on Netflix.”

It turns out the broadband maps may not be entirely accurate, either. When Kenny Sherin, broadband access and education coordinator for NC State Extension, looked up the home address for his parent’s farm on the map, he found a glaring inaccuracy. “They have farm buildings around the property, including an old chicken house that we now use for storage. Their residential location dot for their address was on that chicken house. Their home did not have any dot on it,” said Sherin. “In FCC land, their home doesn’t matter because it’s not a dot on their page.” So he filed a location challenge on the map, and implores others to check the map for accuracy and file a complaint if they notice any discrepancies.

“In the farmer residence, where the farmer lives, it’s important to have coverage,” said Sherin. “But their farm office might not be in their house, it might be in their shop, which needs to be indicated with a dot on the map, too.”

Getting broadband internet to all Americans is an ambitious endeavor, but the livelihood and businesses of farmers across the country relies on it. The importance of expanding connectivity “goes beyond bingeing on Netflix,” said Sherin. “We’re talking about how do we increase our earnings? How do we learn something new? How do we connect to telehealth resources? How do we earn, learn and be well through digital resources?”

For Buckmaster, efforts to improve broadband in rural areas won’t be a complete success until the entire map is covered. “It can’t just be to the house or the office or the barn. It’s got to cover the landscape,” said Buckmaster. “Do you have connectivity to every field in that township in that county? If you don’t, you haven’t provided broadband connectivity to agriculture — not until essentially it’s in every field in every township in every county in every state.”