The low-rent app helped millions of city residents discover foraging — long before the pandemic opened the floodgates.

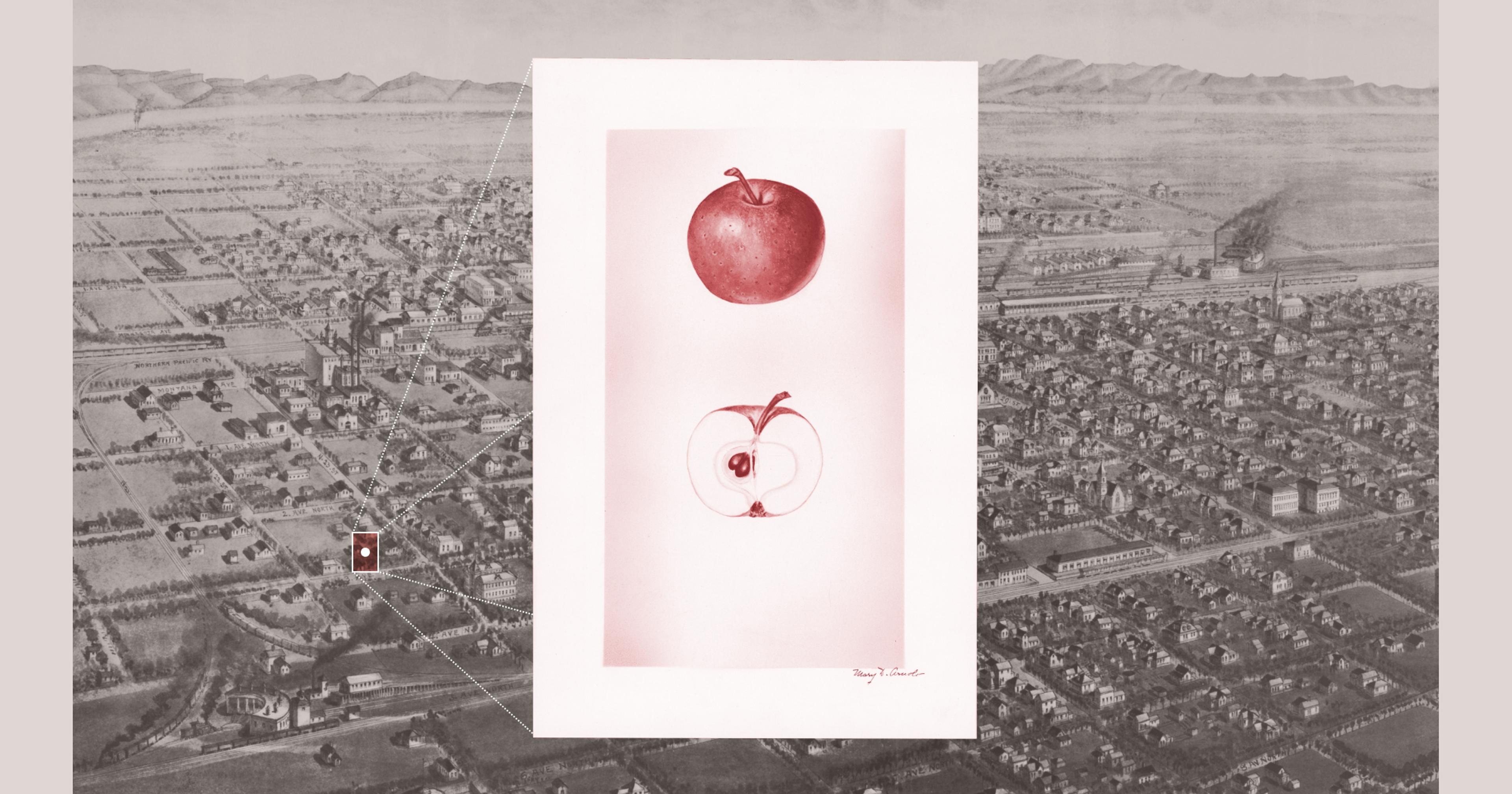

In 2018 Billings, Montana, had a couple of divergent problems on its hands.

In the quickly growing city, nearly 20 percent of its residents have been labeled as “food insecure.” Many of those people were clustered in the South Side neighborhood, where nearly half of the area’s population lives below the federal poverty line.

At the same time, there was an embarrassment of crabapple trees dropping fruit, making a mess of its public parks and sidewalks.

Those two conflicting issues, sitting at very different ends of the importance spectrum, came together at the tip of a robust movement to connect communities with the wild foods in their own backyards. What if the city’s underused fruit trees could be used as a resource for local residents who lacked access to fresh foods?

In 2018, Billings’ municipal government began identifying fruit trees within its park system and mapping them on FallingFruit.Org, arguably the largest database of edible plant locations in the world.

Launched by avid foragers Ethan Welty and Caleb Philips in 2013, FallingFruit’s interactive map has become one of the easiest access points for city dwellers who want to dig into the world of foraging — a movement that took off during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic. A decade into the groundbreaking site’s existence, foraging has moved from the periphery toward the mainstream, inspiring forward-looking municipalities to embrace its benefits.

Here’s how it works: Users either type an address in the app’s search bar or zoom in to a neighborhood on a map. There you’ll see an array of dots; each one names a variety of fruiting bush or tree that’s been pinned. Click on one and a box pops up with a fuller description that tells you the best month to harvest the produce, whether it’s entirely or partly on public land, and, in some cases, offer harvest reviews. It also links to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s species profile. One newer feature allows users to narrow their search to invasive species that are available for the picking.

During the height of pandemic lockdowns, internet traffic on foraging skyrocketed by up to 500 percent in the United States. FallingFruit’s traffic jumped roughly 40 percent from 2019 to 2020 due to this surge. “It’s complicated to forage,” said Welty. “[FallingFruit] is a way of communicating how much food one can find in their city — it’s a way of reframing the city.”

More than two million users in 214 countries have viewed FallingFruit’s free website and 99-cent mobile app that pins fruit trees, berry bushes, and other plants. For freegans, it also highlights diveable dumpsters, which can be illegal to glean from but nevertheless follow the site’s guidelines of urban harvesting. It boasts more than 1.5 million locations, at least 60,000 of which have been added organically by users.

“I think that’s the reason this program has survived 10 years without funding to be honest,” said Welty, who moderates the site in between child care and his full-time career in glaciology. He hopes to launch a harvest calendar and other useful features in the near future. “It’s really, really being used by people.”

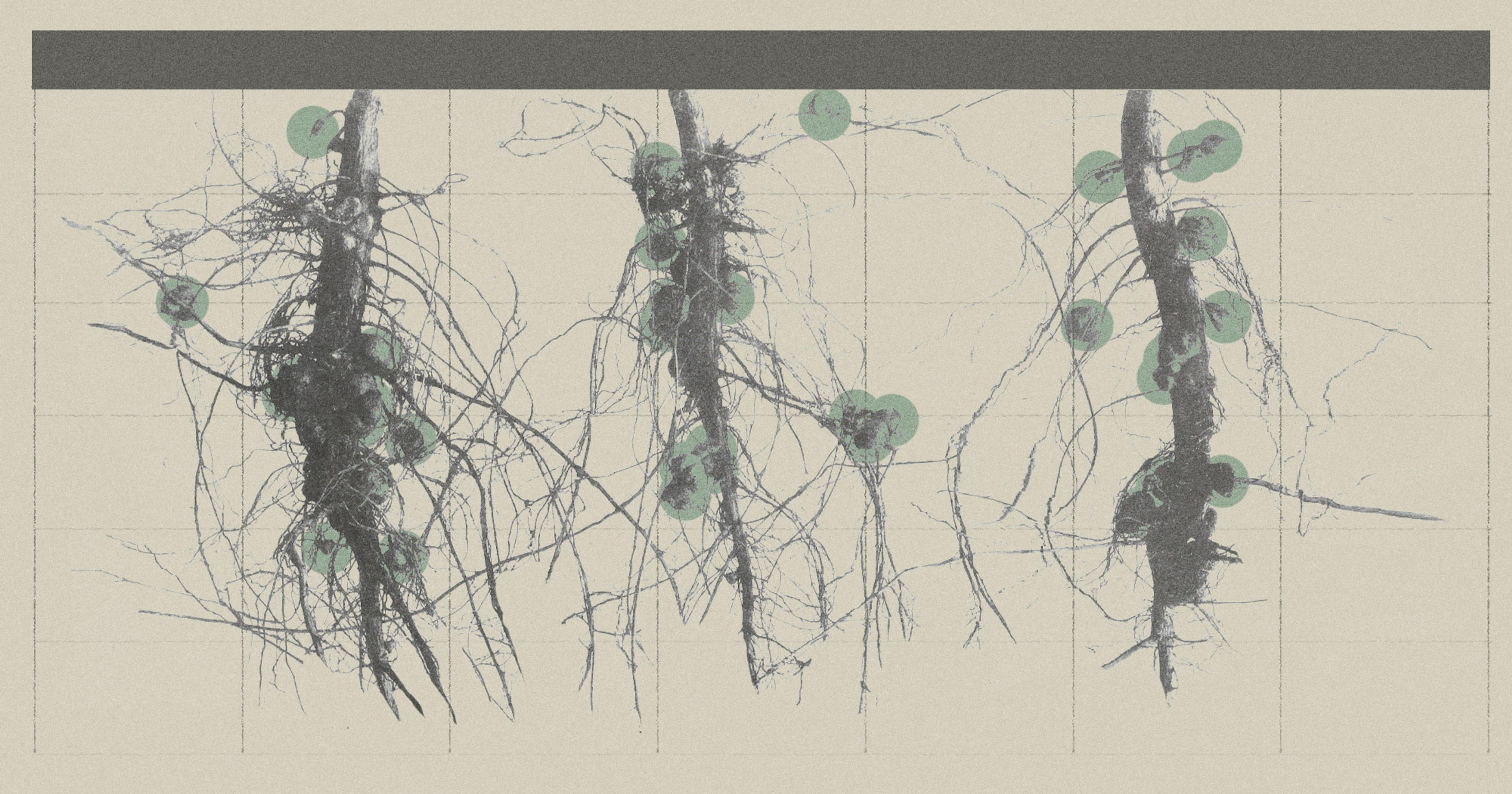

The site has incorporated nearly 1.5 million pins of municipal data from around 50 cities, but Welty is currently trying to figure out an easy way to add tree inventories from 1,000 more.

“It’s bringing more of a neighborhood feel, so they feel like more of a community.”

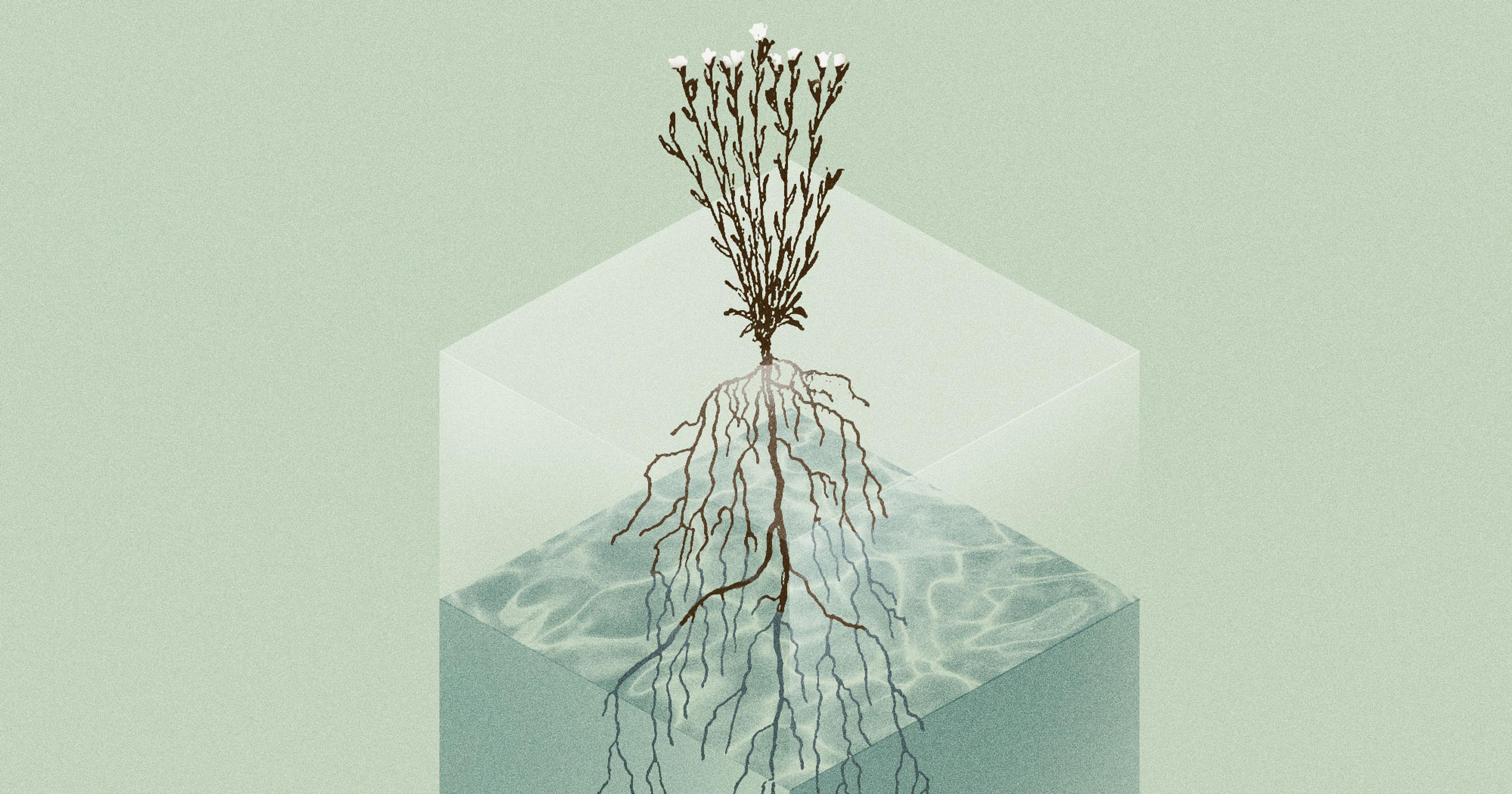

Some city governments, like in Austin, Texas, and Billings, have directly sent their data to FallingFruit in an attempt to encourage residents to take advantage. These partnerships show shifting perceptions in how cities can provide food assistance, a concept that urban planners are starting to realize may provide numerous benefits. Studies have shown that urban foraging boosts social-ecological resilience — the complex dynamic between humans and their environment, especially in reaction to climate, economic, and disease disruptions like Covid-19.

Though increasing access to fresh foods is an important component of Billings’ Parkland Gleaning Project, another goal has been to get the community to spend more time together in nature. Anyone can pick fruit from approximately 100 trees, which includes apples, pears, plums, and cherries, all of which are pinned on FallingFruit’s map. “It gets people to come to the parks who normally wouldn’t come,” said Mike Pigg, director of Billings Parks and Recreation. “It’s bringing more of a neighborhood feel, so they feel like more of a community.”

Officials are still working toward identifying additional spaces to expand access to the program. “We will definitely plant more fruit trees and have more gleaning spaces,” added Pigg.

Some organizations, like The Berkeley Food Institute, have voiced support for these kinds of municipal projects and actions. In a 2017 policy brief, it found “foraging could provide a supplementary food source within the urban and peri-urban landscape as part of a multi-pronged strategy to help address socioeconomic inequities in access to nutritious foods. ”

“She really believes in eating in a way that’s not only connected to the earth but also is really nutrient-dense and better for you. It’s like an ancestral form of eating.”

Even before the current uptick in interest, foraging has long provided supplementary nutrition for many people, especially in some immigrant communities.

Food writer Dakota Kim has written about her experience growing up poor in rural central Illinois, and feeling ashamed by her mom’s foraging traditions. She remembers pulling stalks of asparagus from plants her mother found on the side of the railroad tracks. “I did not think it was cool,” she said. “It was embarrassing to me because I felt like none of the other kids at school were doing this.”

As foraging has become more popular, she developed a deeper appreciation for her mother teaching her these ancient traditions. During the pandemic, the pair regularly went out searching for wild foods in Kim’s upscale Southern California neighborhood, picking up ingredients like gingko nuts and acorns for traditional dishes like jook and acorn jelly. “She really believes in eating in a way that’s not only connected to the earth but also is really nutrient-dense and better for you,” says Kim. “It’s like an ancestral form of eating.”

The mother-daughter duo have also found and dried persimmons and loquats in South Pasadena for tea, to the envy of some. “It’s definitely seen as very cool now in some circles,” said Kim.

“There’s also been a lot of unease about someone using that space for sustenance — it feels inappropriate to a lot of people.”

Still, not everyone gets it or understands the laws on urban gleaning. While Kim likes to use FallingFruit anytime she’s strolling a new neighborhood, she is always careful to follow local rules. She follows a foraging code of conduct to not take anymore than is needed (or ⅓ to ¼ of what’s available, depending on the forager being asked) and, to avoid potential racial confrontations, dresses nicely and avoids foraging anything from private property if there is no one to ask permission. Public property, however, is fair game. “My mom knows this too,” said Kim. “It’s okay as long as it’s hanging over a public area.”

Access and understanding the gray area between public and private lands are the two areas that stir the most controversy when it comes to urban foraging. As FallingFruit continues to spread — half of its users and locations are now outside the U.S. — advocates like Welty hope that larger adoption will help suspicious neighbors to reconsider what is considered edible. Welty considers the addition of dumpsters to dive, edible fruit grafting projects, and invasive plant initiatives as important milestones for the site.

“Ten years ago, urban foraging felt fringe,” he said. “I had a lot of personal experiences where people were often amazed and interested in stumbling along someone foraging, but there’s also been a lot of unease about someone using that space for sustenance — it feels inappropriate to a lot of people.”

In Billings, there’s still a long way to go in educating locals about the free food sources located within its city parks. But Pigg has seen firsthand how locals react when they do realize the abundance of fresh fruit that dots their city landscape — an initiative that has been strongly influenced by the widespread adoption and technology-driven data of FallingFruit. “Once they start to realize, they get excited about it,” he said.