The agriculture specialists at Customs and Border Protection toe a tough line against America’s enemies — pests and diseases that could decimate our domestic food supply.

There’s a modest room inside Cargo Build- ing 79 at John F. Kennedy International Airport, a dizzyingly massive hub for American Airlines’ cargo shipments. It’s a windowless little space, quite plain save for an oversized American flag, a row of stainless steel tables, and a desk.

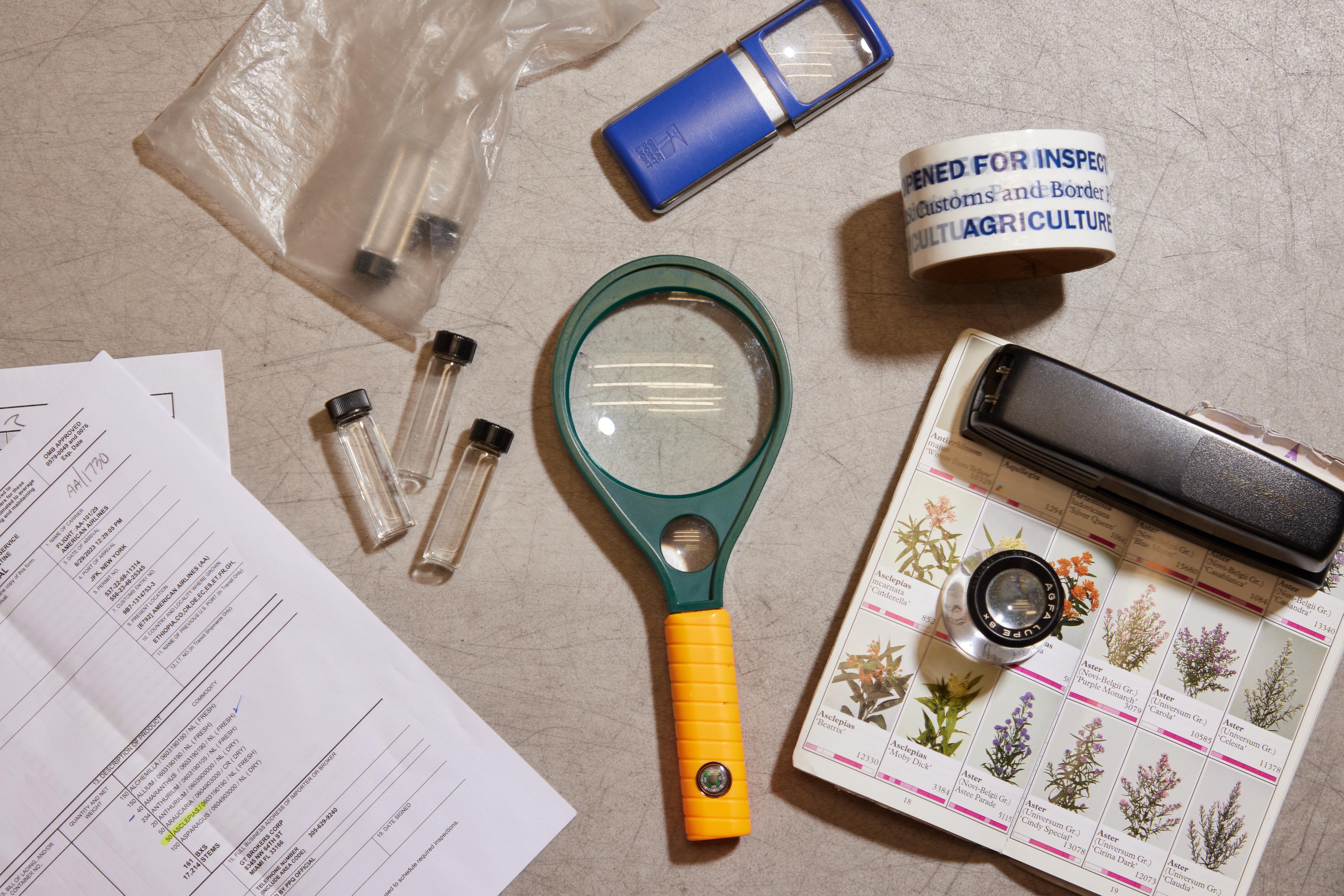

Tools of the trade.

Inside the desk is an array of old-timey accouterments that Wes Anderson might choose to give a private detective in one of his films: magnifying glasses, vials, tweezers, faded field guides to botany. But these are no props, and if they seem a bit worn it’s not from neglect — it’s from daily use. This is the toolbox of the agriculture specialists at Customs and Border Protection (CBP), tasked with the sacrosanct duty of keeping invasive pests and diseases from entering the United States.

“One bug, just one or two millimeters long, can hold up tens of thousands of dollars worth of product,” said CBP supervisory ag specialist Ralph Johnson, while eyeballing an array of high-end peonies, fresh off a flight from the Netherlands.

It’s not surgery, but inspecting high-end flowers does demand a certain degree of delicacy.

Johnson and his cohort do not carry guns; street drugs and immigration are not in their purview. Rather, these agents serve as frontline protection from pests and pathogens with the potential to all-but-decimate the American food supply. Take hoof and mouth disease, that infamous livestock malady which could cost the U.S. more than $200 billion if we see another outbreak, according to the USDA. Or massive African land snails, which likely entered the U.S. in Miami and have since been merrily destroying Florida’s croplands.

At JFK, the ag specialists work on two fronts, passenger and cargo. Inspecting the latter has business impacts that can frustrate shippers and wholesalers, but comes with the territory. But when a CBP agent confiscates some passenger’s precious lemons, picked from a grandmother’s tree in Sicily for a family celebration thousands of miles away, that’s when it gets personal.

While many confiscated items are no more interesting than a tangerine, there are also ostrich eggs and sheep horns and giant snails. (Pictured: Branch chief Rose Andretta)

“Taking people’s food is very intimate,” said Ginger Perrone, a CBP agriculture supervisor on JFK’s passenger side. “They often don’t understand why we’re doing it ... there’s been a lot of tears.”

Perrone’s team destroys huge batches of edible contraband every day: prosciutto and peppers, pork buns and pineapples. They know their mission is vital, though it can be hard to steward such waste. “People think we take home all the food we confiscate,” said Rose Andretta, agriculture passenger branch chief at JFK. “It’s actually just sad to throw it all away, but we are the first line of defense in protecting our nation against harmful pests and diseases.”

Branch chief Andretta chops up charcuterie and fruit before washing it down a huge garbage disposal.

Back in the inspection room in Cargo Build- ing 79, Johnson’s colleague Peter Pramberger has just finished thrashing bunches of purple larkspur, scouring for unwanted hitchhikers as a shower of petals drifts to the floor. It’s meticulous, repetitive work, using eyeballs, knowledge of botany and entomology, and a set of crude, analog tools. But Pramberger loves it.

Purple rain: Ag specialist Pramberger looks for hitchhik- ers as petals drift slowly to the ground.

“The work we do is so important,” he said, “but I also just love smelling these flowers.”

This article first appeared in the Ambrook Research Journal V. 01, a limited-edition print publication.