Deep in Missouri caves, millions of pounds of cheese reveal how federal dairy policies shaped our diets, food aid, and ideas of government waste.

This is an op-ed. It does not represent the perspectives of Ambrook or this publication.

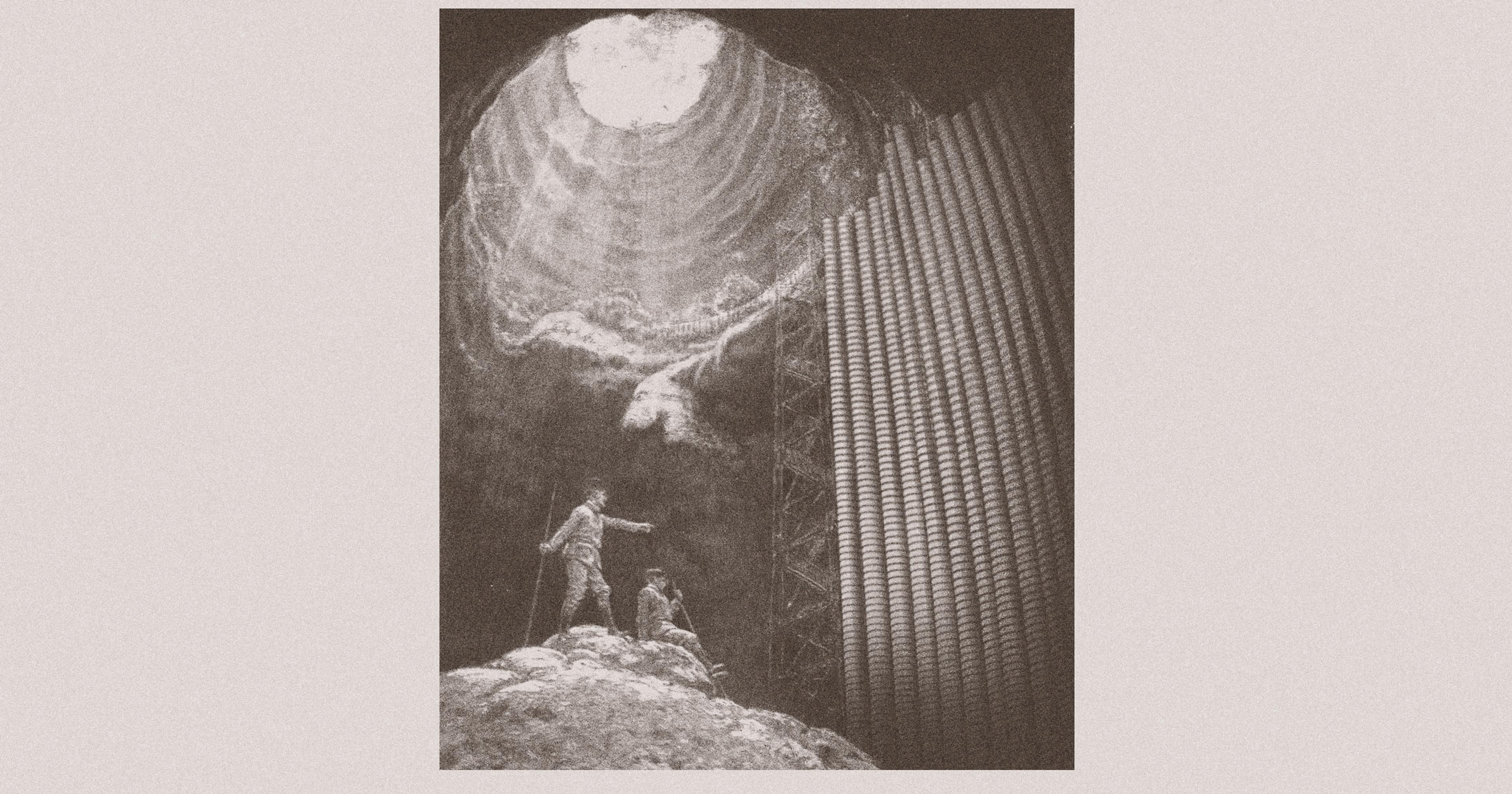

More than one hundred feet beneath the ground in Springfield, Missouri, there are expansive, dimly lit limestone caves. These caves are not filled with either iridescent hanging stalactites nor emerging, rocky stalagmites. Instead, the football-field-sized caverns are stuffed to the brim with American made cheese: cheddar, Swiss, provolone, and even a room dedicated to Wisconsin curds. The original owner of these infamous cheese caves? The United States government.

For decades, it was official American policy to purchase and store massive amounts of cheese in Missouri, Wisconsin, and Kansas. In the intervening decades, a company called Springfield Underground has taken over operations. While the USDA itself no longer actively stockpiles cheese in the caves, their use for storing immense amounts of dairy products continues, a quiet testament to the persistent overproduction baked into federal dairy policy.

The story of how the government came to store millions of pounds of cheese underground begins with the Great Depression. As prices for agricultural products collapsed in the 1930s, dairy farmers across the country faced financial ruin. Despite their pleas, distributors refused to raise their prices, convinced Americans would not pay a premium for a pantry staple. Infuriated, farmers took to the streets, sabotaging milkmen on their delivery routes and pouring gallons of milk on the ground to make their point.

They won: Franklin Delano Roosevelt offered subsidies to farmers who agreed to reduce their production in order to raise milk prices. While FDR’s policies planted the seeds of federal agricultural intervention, they would pale in comparison to what came later.

Throughout World War II, the American government touted dairy production as a vital contribution to the national war effort. They shipped dried milk to soldiers overseas, and new research about milk’s ability to build muscle mass made it the ideal beverage for the nation’s virile self-image. “If you read the literature from the 1940s, there’s an almost religious feel to the discussions of dairies‘ powers,” said Andrew Novakovic, E.V. Baker Professor of Agricultural Economics Emeritus at Cornell University. (A glowing pamphlet from the era described cheese as ”a food no one should live without.“) Soon, this belief became law. In 1946, Congress signed the 1946 National School Lunch Act, which required every meal served in schools to include milk.

But milk presented a logistical challenge. It was easily perishable, costly to transport, and difficult to store. For many dairy farmers, the precarity of their product necessitated a consistent, stable consumer. To promote production, Congress passed the Agricultural Act of 1949, which included the Milk Price Support Program (MPSP). The program guaranteed a minimum price for milk and authorized the USDA to buy the surplus when prices dipped below the support level. With the government as a buyer of last resort, production among dairy farmers soared. With their newfound certainty, they raced to churn out as much milk and cheese as possible.

That trend intensified under President Jimmy Carter. A peanut farmer from Georgia with deep ties to rural America, Carter viewed price support as a lifeline for struggling farmers, many of whom were being crushed by inflation and rising input costs in the 1970s. While running for president, he promised to raise the price of support for vulnerable dairy farmers and when elected, followed through. The result was a dramatic oversupply of dairy. Since it spoils quickly, the U.S. government encouraged producers to transform their milk into cheese, and the USDA began stockpiling the surplus in warehouses across the country, including deep underground in Springfield, Missouri. At its peak, the government spent over $2 billion a year to store the excess, much of it entombed beneath the Midwest.

For many dairy farmers, the precarity of their product necessitated a consistent, stable consumer.

When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981 promising to slash federal spending, the cheese stockpile became a symbol of a bloated government. In an infamous press conference, Reagan’s Secretary of Agriculture, John R. Block, held up a five-pound brick of processed cheese and declared, “We’ve got 60 million of these that the government owns. It’s moldy, it’s deteriorating ... we can’t find a market for it, we can’t sell it, and we’re looking to give it away.” Some critics proposed dumping it in the ocean. Instead, amid rising hunger and a recession, the Reagan administration created a solution: Give it away. The USDA began distributing the surplus through food banks, churches, and welfare offices. This marked the beginning of what became known — often mockingly, sometimes gratefully — as “government cheese.” (Not to be confused with the new TV show of the same name.)

To many, the image of government cheese embodied the contradictions of federal policy. A symbol of waste born from overproduction and bureaucratic miscalculations yet also a lifeline for millions of food-insecure Americans. The dense, salty cheese was emblematic of the era’s social safety net: essential, flawed, and stigmatized. These contradictions were used to justify sweeping changes. Under Reagan, the federal government began scaling back and privatizing key food assistance programs, leading to a major reduction in SNAP. The public image of food aid shifted from a social right to a begrudging handout.

Today, the former government cheese caves are still operational, but the Department of Agriculture is no longer their primary tenant. The Springfield Underground complex has been transformed into a vast industrial logistics hub, with over 3 million square feet of temperature-controlled storage leased to corporations like Kraft Heinz, PepsiCo, and Nestlé. Some of the same companies that benefited from USDA dairy surplus purchases during the program’s heyday now rent space in the very caverns once used to house that surplus. These artificial caves maintain a steady 58 degrees year-round, making them ideal for storing perishable goods including cheese, which is still housed there, albeit now as private inventory.

“We’ve got 60 million of these [blocks of cheese] that the government owns. It’s moldy, it’s deteriorating ... we can’t find a market for it, we can’t sell it, and we’re looking to give it away.”

While the U.S. government no longer actively stockpiles cheese, the surplus problem hasn’t entirely disappeared. In 2022, the USDA reported that commercial inventories of American cheese topped 1.5 billion pounds, the highest level since the 1980s. Though most of that cheese is now stored above ground in refrigerated warehouses, the symbolism of the caves persists and is often invoked during debates over agricultural subsidies and food aid.

Dozens of viral TikTok videos continue to show the Springfield cheese caves with a mix of befuddlement and pride. “This is where our taxes go?!” writes one user; “God Bless America,” says another. Despite privatization, the caves remain a subterranean monument to the country’s ongoing struggle to balance food security, farm economics, and public perception. Government cheese, once a symbol of abundance and attempts to help small farmers, has continued to be a symbol of government dysfunction — a stigma that persists to this day.

In President Trump’s “one big beautiful bill,” which passed the U.S. House of Representatives last week, federal funding for SNAP would decrease by more than $267 billion over 10 years. The impact of that cut would be enormous: More than 40 million Americans rely on SNAP, including one in five families with children. Like in the 1980s, accusations of government waste have fueled calls to reduce the social safety net. Once again, dairy is at the center of the story — but this time, the industry could face a major loss.

According to Mother Jones, the dairy industry still receives nearly $1 billion a year in subsidies. Perhaps the largest, least visible subsidy flows through federal food programs like SNAP, WIC, and school lunches. A prime example: Every federally reimbursed school meal must still include a carton of milk regardless of whether or not students want it, need it, or can even digest it. Some students have even protested and won lawsuits over the fact that they need a doctor’s note to receive soy milk.

“Every dairy producer I work with is aware of this connection [with the federal government] and many are frustrated by it.”

This creates an enormous, federally subsidized market for dairy. In fact, recent bipartisan legislation proposed by the dairy lobby would expand this requirement to include whole and two percent milk, bringing more milk into American schools. “Dairy producers understand that they are deeply intertwined with federal food aid programs,“ said Novakovic. If the Republicans‘ proposed cuts go through, the benefits could profoundly impact their bottom line. ”Many dairy producers who supported [the President] are surprised to see the proposed cuts.“

Luis A. Ribera, professor and extension economist at Texas A&M, agrees. “Every dairy producer I work with is aware of this connection [with the federal government] and many are frustrated by it,” he said. Most would prefer open international markets as a release valve for their products, selling cheese in places like Canada and Europe, where import restrictions remain tight. Their goal isn’t to produce less dairy, despite the fact that fewer Americans are drinking milk than ever before. Activists argue that instead of subsidizing a fading industry, federal policy should pivot toward emerging, climate-conscious alternatives like almond, soy, and oat milks.

At a time when federal food aid is once again under attack and claims of government waste abound, it’s no surprise that the cheese caves have resurfaced in the public imagination as viral symbols of confusion and government excess. While today’s debates may feel new, the entanglement between the dairy industry and the American government is anything but. With dairy exports declining and domestic surpluses rising once more, it’s not unthinkable that the government could once again return to the caves or finally shut off the milk spigot once and for all.