The only child of an 82-year-old Wisconsin farmer considers what’ll happen when she inherits the family farm.

There’s a meme that says, “If you’re an eldest daughter, you might be entitled to compensation,” a play on those class action commercials for mesothelioma or mesh bladders or Camp LeJune water. I’m an eldest — and only — child, a daughter of dairy farmers. I should be entitled to a lot of compensation, when I reflect on the process I’m mired in.

This process is farm succession, and wow is it hairy.

My parents are in their early 80s. Thankfully, both are mentally capable and mostly mobile. My dad’s 60 years as a dairy farmer has chewed up the cartilage in his knees; my mom, who spent 30 years as a registered nurse, has two titanium knees which serve her well.

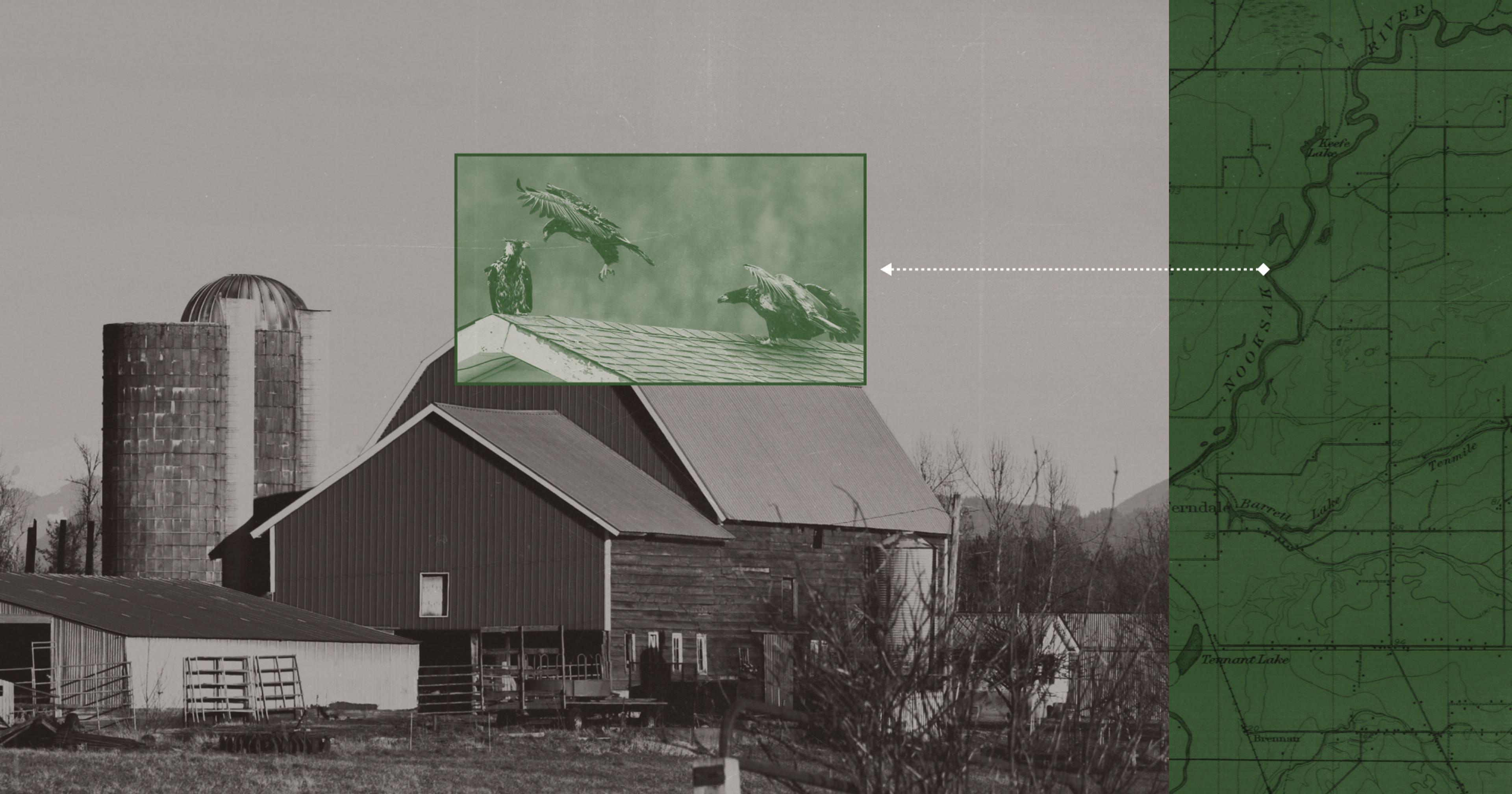

We had a dairy farm for my entire childhood, which was small even by Wisconsin standards: 35-40 cows milking at the most, about 10 yearling heifers, and 6-8 calves at any given time. Currently, we have 13 Red Angus cattle who are rotationally grazed. Besides the cows, our farm included a stanchion barn with a pipeline setup for moving the milk to the bulk tank, two border collie mixes, and a healthy number of barn cats. For cropland, we own about 100 acres of rolling hills, one sinkhole, a weedy pond that my mom swore had such fragile banks that I would immediately fall in if I set foot near it, and one weird forested ridge where a skunk family perpetually denned.

Technically, I am a fifth-generation farmer. As someone who excelled in school and music, who was sorta interested in the farm but not always, I have a particular relationship with my dad: He is somewhat open to my opinion, but he makes the final decisions. This makes sense — he’s 82 years old, and has the experience of being a full-time farmer since he was 20.

Compared to other farm friends, I had a relatively easy early life. I chose if my chores were inside (doing dishes) or outside (bottle-feeding calves) during the school year. During summer I added in 4-H projects and unloading hay wagons. I enjoyed the land and the animals, but had an uneasy truce with the rest of it: the uncertainty of the weather causing my parents stress, the machinery that always broke at the exact wrong time, the volatility of the markets.

In high school, as I became more interested in genetics, my dad listened to me about which bulls from the artificial insemination catalog to breed our cows with. I showed calves and cows at our local county fair through 4-H; one year, Lisa, a homebred heifer, won both her yearling class and a showmanship class. When my parents retired from dairy farming to have a small beef herd, Lisa was the only dairy cow who lived out her days on the pasture.

I took over evening milking while I was in college, from starting set-up to walking the last cow out of the barn. This gave me confidence in dairy farming, and confidence in general. Though my dad and I came as close to a partnership as we ever did those summers, we never directly talked about me taking over the farm. Milk prices were low, the work was hard, and I was good at school. At the time, farming seemed like something you did if you had to, not because you wanted to; I see now this is not true for all farm families.

The author with her mother and father in 1982.

I became a teacher, found fulfillment in that for 14 years, until I made a career change to work in state-level government. Now I work from home while considering what I want to do with the farm. I think about what I want for my life, how the legacy of my farm family fits into that, and if I’m honest, how the pull of the land and the animals fits into who I am.

In 2016, we attended a ceremony at the Wisconsin State Fair for families whose farms had been owned by the same family for 100 or 150 years. It was maddening. We listened to speeches from muckety-mucks about how “farming is a way of life” to be celebrated, as we ate pancakes on Styrofoam plates. Minutes earlier, my dad had looked at me outside the tent and said, “I didn’t think I’d be around to see this.” It was 7:30 am and I had been up since 4. “Excuse me, dad?” “I went to this fair with your grandma when the farm was 100 years old. I didn’t think I’d make it 50 years.”

After that abrupt emotional vulnerability, I wasn’t ready for anyone’s empty words about supporting farmers. The speakers were politicos who could, say, fix the broken milk pricing system, yet chose not to. They would still break their arms patting themselves on the back while repeating clichés about farming to people who actually farmed.

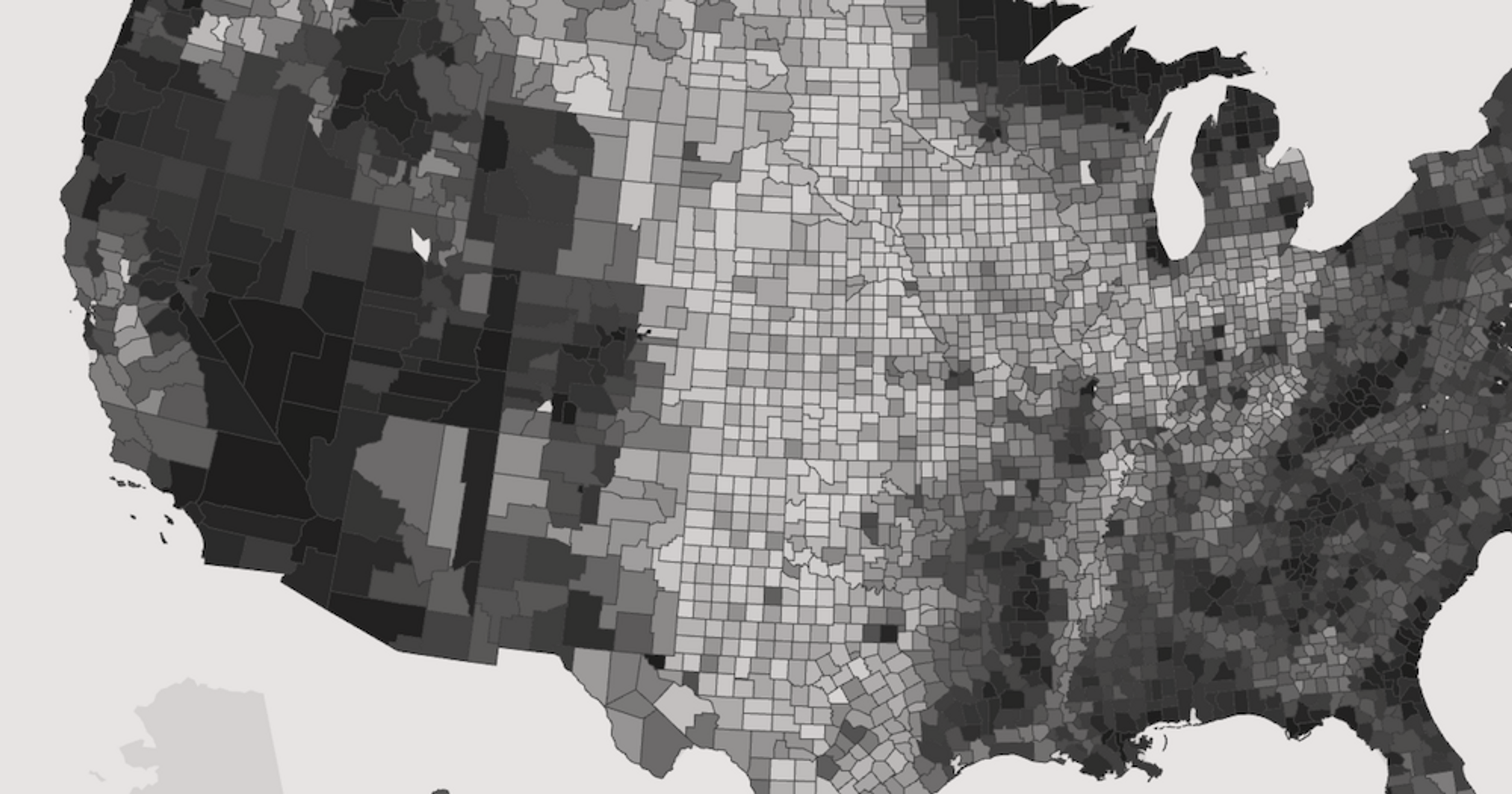

Wisconsin had lost many dairy farms that year — it ended up being the beginning of the most recent dairy crisis in the state, and here they were telling us how much we mattered. I think affordable health care or higher milk prices might be a better topic, but what do I know?

This is all background to where I am now. All that I carry with me into succession planning — my complex feelings around the farm, my parents and their lives, how farmers are treated, and what a legacy means. What does it mean to have 100 acres of farmland entrusted to me, close enough to a city where it is attractive to developers? I’ve already received one clumsily written letter from a high school classmate’s brother who asked if we ever thought about developing the land.

The author's dad in the 1981 Wisconsin State Journal.

Sometimes I think about my ancestors who farmed because they needed to and what they would say if I explained my job now — an information worker who clocks most of her hours from home. Would my great-grandfather say, “Let me get this right, you can work inside and don’t have to do manual labor? Of course you should work inside! Sell the land, get a nice boat, and enjoy life! This is what success is!”

I think about the over-romanticization of “working the land” and the lore of farm families — even the idea of celebrating a farm that’s been in one family for 100 or 150 years. What does that actually say about land? Wrapped up in this, too, is how Wisconsin stole the land from Indigenous people and then my ancestors bought that stolen land. I think about that also. I don’t know what to do with it, but it’s there.

I think about how I could use part of the land as a teaching farm for people who want to learn how to farm, particularly to rotationally graze cattle. Or I could rent part of the land out for beginning vegetable farmers, or turn it all into pasture and expand the beef herd and have a direct-to-consumer business.

The hard part is that when I mention new ideas to my dad, he points out all the negatives. He’s risk-averse, I get that — he has shepherded this farm through multiple crises, including our barn burning down in 1997. I’m in this push-pull space of wanting to learn from my dad, needing his knowledge, but not getting to try out any new ideas because he’s still in charge and isn’t open to change. Yet, I fear he will be gone soon and I won’t get to ask him any of the questions I have.

In terms of succession, moving the estate to the next generation is functionally easier with just one child. In terms of what I am going to do with the land, that’s much harder. It feels like there’s such an opportunity here to do good in the world and not just make money. My family has never been about that — my grandma was a one-room schoolhouse teacher, my grandpa, a farmer. At times, the land and the tradition of farming feels like the only connection I have to my family: my immediate family and my ancestors.

My grandparents’ home farm is on a road named after our family, specifically, my great-great-uncle who owned the first farm on it when the town was formed. I can see the privilege I have in inheriting this land, the farming tradition, the knowledge, and the tangible machinery and tools. I am balancing maximizing the good that can be done with recognizing how hard this life can be. I’m trying to honor what I’ve been given from the past with who I am as a person, now in the present.