Along with chemical inputs like glyphosate, Eric Williamson uses grass-fed cows as a tool, to improve the soil health on his Washington farm.

Washington’s farm-filled Quincy Valley is so flat that even through a haze drifting down from late-spring Canada wildfires, you can see clearly from one orchard- and vineyard-planted hillside to its opposite 30 miles away. In between, feedlot cows lie glumly on bare hillocks of dirt and a dragonfly-shaped helicopter zips low to the ground, spraying crops. Somewhere in the middle of all this, along a road so straight there’s nowhere to hide and no way to get lost, stretches Eric Williamson’s 6,000-acre vegetable farm. In an area where “everybody’s in agriculture,” he said, “we’re seen as a little bit on the ‘green’ side.”

Williamson is a conventional farmer raising sweet corn, green peas, lima beans, carrots, and bell peppers for the frozen and pickling markets, as well as grass seed, canola seed, and seed garlic. Although there are a few organic farmers working throughout the valley, Williamson, who talks breezily and assuredly about the pros of glyphosate, is not one of them.

What he is is a proponent of building soil health, in a sandy region plagued by winds strong enough to scatter your growing medium and ruin your crop. “When I was a kid, there would be drifts over the road, like snow drifts, but it was just blowing sand,” he said. For Williamson, improving rather than “mining” the soil means raising eight or nine crops rather than just potatoes or rice or onions, because “It’s good for the ground to have different kinds of roots, different kinds of organisms.”

It also means figuring out how to reduce tillage, which can lead to soil erosion and compaction; Williamson no-tills or strip-tills where he can, in the latter instance disturbing only the rows where seeds will go. It means cutting back on the chemical inputs that can kill off much-needed soil organisms. It means growing cover crops on almost every acre, to keep the soil anchored and add to its nutritive value. And all of that, believe it or not, means bringing in some cows.

Eric Williamson displays some cereal rye, one of the cover crops he uses on his 6,000-acre farm.

·Photo by Lela Nargi

Every winter, as many as 2,500 heads of cattle are sent to Williamson by ranchers who are fellow members of a regenerative-certified collective. These are beef cattle that will graze and forage their way through their two years of life — no grain finishing, no feedlots. Williamson gets the bovines in the winter months, when the grasses on their home ranches in Washington, Oregon, and Montana are sparse; in summer they cycle on from too-hot Quincy to other, cooler parts of the Pacific Northwest.

“A lot of the ranches that [the cows] come from are set up for summer grazing and they have a lot of good grass through the summer,” said Williamson. He also sometimes purchases calves of his own, to make up for gaps in the collective’s cattle slaughter and keep production consistent; like other collective members, he is paid a set price for the meat when it’s processed. But in between vegetable growing seasons is an opportunity for those cows to graze when grasses have died down — and for some of his 20 full-time workers to stay employed caring for them in the off months. “If it weren’t for the farm, the cattle business probably wouldn’t work very well here,” Williamson said. “In the wintertime, when there’s nothing growing here, the cattle utilize underutilized resources.” Those resources? His cover crops and the abundant crop residues left over after harvests.

Williamson started cover cropping in the early 90s, “before it was popular,” he said. “Then we thought, we can either harvest this for hay, or cattle can graze it.” Cover crops like the wheat and triticale he grows help with soil fertility “and you can use them to capture deep nitrates [in the soil] and bring them up where the cattle can graze, and they redistribute the nutrients around the field.”

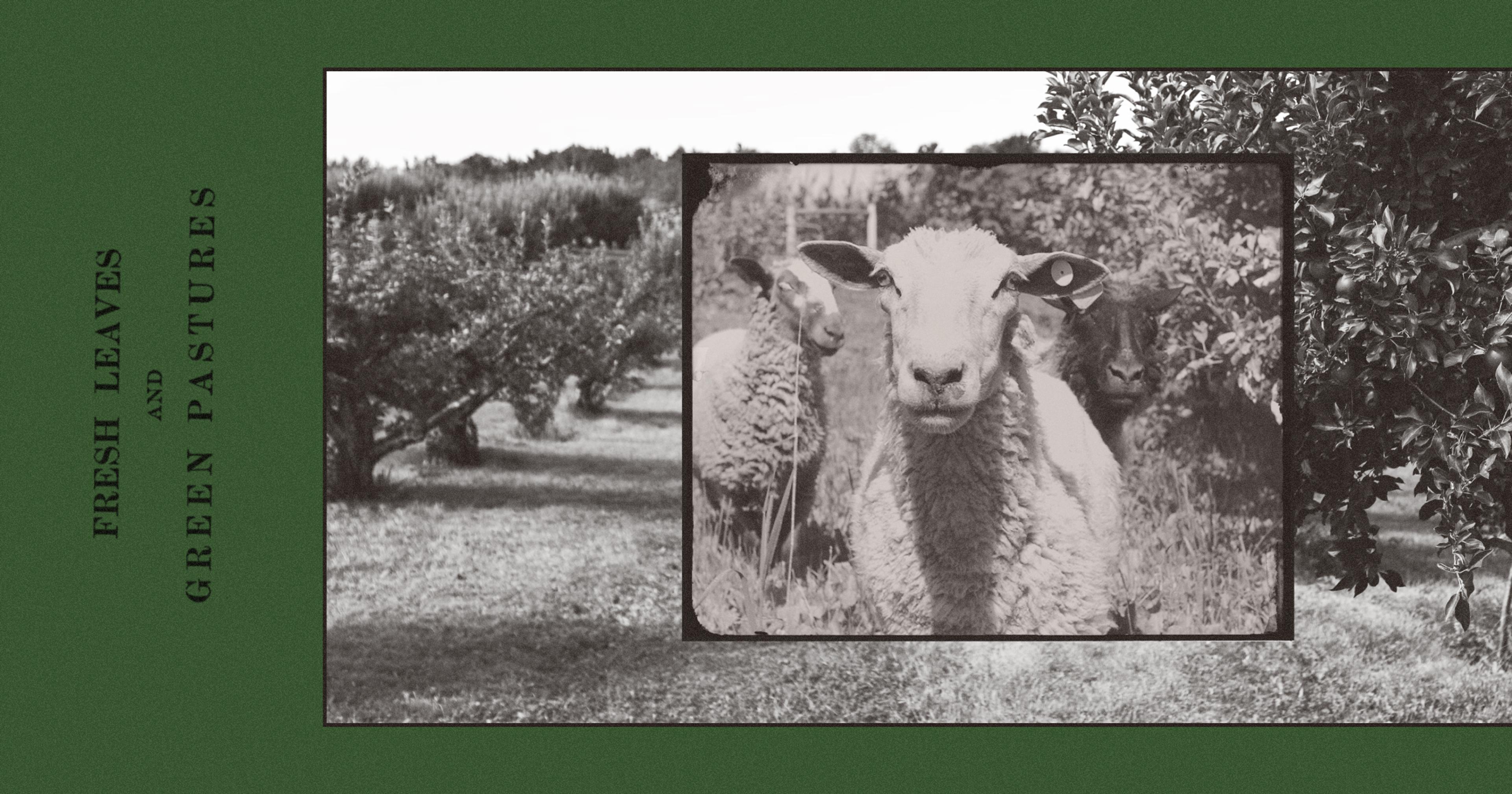

Some of the cows that overwintered on Williamson's acreage.

·Photo by Lela Nargi

He also began reducing tillage where he could — although some crops, like carrots, need to be grown in raised beds and intensively tilled so their greens can be efficiently sliced off before chopping and freezing. Still, Williamson explained, with all the cover cropping and grazing and minimized tillage inherent in the system he’s been hashing out over the last 20 years, “The water-holding capacity of our soil has probably doubled and our organic matters have really improved. That actually allowed us to grow crops we couldn’t grow before, such as peppers and garlic that have shallow root systems, so they need a good reservoir of moisture.”

Cattle also forage certain crop residues that might otherwise gunk up farm equipment and increase the need for tilling. This includes copious amounts of green leaves left behind after the harvest of high-yielding sweet corn. “If you can have cattle graze that residue to reduce the load a little bit,” Williamson said, you can make one or two tillage passes on a field and stir up the soil a lot less.

Williamson’s sweet corn crop follows a rotation of green peas. Similar to the residue left behind by the corn, the way the pea vines leave a thick windrow behind the harvester “makes it almost impossible to plant the corn without doing tillage. But we can avoid [that] by harvesting the vines laying there in a big thick row, and they’re pretty good cattle feed.”

Williamson digs up a sweet corn sprout from compacted soil.

·Photo by Lela Nargi

Donald Llewellyn, a ruminant nutritionist and livestock extension specialist at Washington State University Extension, said that there’s lately been renewed interest in reintegrating livestock into cropping systems. With grass-fed cattle, much of their protein, energy, mineral, and vitamin nutrient requirements can be met by crop residues. “And if it’s done by grazing, that has the extra benefit of reduced labor and returning nutrients to the soil,” he wrote in an email.

Each year in the Columbia Basin, which encompasses a wide swath of Washington and Oregon, “many acres of corn stubble [are] grazed … When cattle graze corn stalks they will have access to the leaves, some corn grain on the ground, maybe a bit of cob that escaped the combine, and the stalk itself. Each of these components have a different nutritional value, and they select the best part that they like first (usually the leaves and the corn on the ground) then move on to the other parts.”

In a valley where everyone knows everyone else’s business (and farming methodology), Williamson said some neighbors have begun to take notice of what he’s up to — although there are limitations to implementing his practices. Farmers raising leafy greens need a two-year resting period if they have cattle grazing through, so they don’t risk outbreaks of E. coli. And plenty of farmers, who don’t have a full-time farm crew to support, would rather take a much-needed break in winter than work their way through it.

The day after this photo was taken, these cows would be shipped to another farm in Washington where they could graze all summer.

·Photo by Lela Nargi

Still, he sees that there’s more and more interest in bringing in cattle to build up soil health, “and I know one other guy in our area has started integrating cattle when he grows vegetables,” Williamson said. He also noted that a few “cattle guys” have begun renting fields from vegetable farmers who want their residues grazed but don’t want to purchase the corrals, stock trailers, and other trappings needed to raise livestock. “It’s not a widespread adoption at this point but there’s movement that way. Farming is a really competitive business, it can be really challenging. And I think people are always looking for a way to do it better.” He’s increasingly finding ways to farm better, too. He’s noticed that in denuded fields, “you can concentrate your cattle feeding on that area and really build it up and make it grow.”

“We have a little bit of an advantage being totally integrated, because we can determine what can be grazed and whatnot,” Williamson continued. “Margins are tight and everybody needs to find a way to save a dollar. But I think we’ve also gotten a bunch of other benefits of this, too.”