Farmers worried about avian influenza are trying to zap the wild birds that carry it.

The irony was not lost on Josh Pierce. In 2014, a couple of dozen geese had descended upon his office building in Elmhurst, Illinois — which happened to be the headquarters of Bird-X, one of the country’s biggest suppliers of bird-control products — and showed no intention of leaving.

Pierce, now sales manager for Bird-X, decided to test a solution his company had recently started offering: a handheld laser meant to startle unwanted birds. Like a latter-day Buck Rogers, he strolled out of the building with his blaster, sized up the quarry, and took aim.

“I shined that laser directly at the head of the alpha goose, and my goodness, did they disperse instantly,” Pierce recalled. “It really turned on a lot of light bulbs. If we can actively connect with bird flocks out in the field the way that I just did, we really might have something here.”

Livestock farmers across the U.S. have been reaching similar moments of laser-driven enlightenment. As poultry and dairy operations struggle with the ongoing spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza, they’ve sought to reduce the risk of their animals contracting the disease. Farmers know that wild birds such as geese, ducks, and seagulls spread bird flu along their migration routes, and lasers are becoming a go-to tactic for keeping them — and by extension, the virus — away from buildings or pastures.

Scientists have looked into lasers for bird control around airports since the 1970s, said Rebecca Brown, chair of plant sciences and entomology at the University of Rhode Island, but comparatively little work has examined their use in agricultural settings. She and her husband David Brown, a professor of computer science at the same university, published the first study of “laser scarecrows” for protecting cornfields in 2021. (They’d been asked to look into the technology as an alternative to gas-fired startle cannons, which regularly draw noise complaints.)

The theory of why lasers work is fairly straightforward. “Birds primarily rely on vision to interact with the world and sense threats, and their vision is much better than human vision,” Rebecca Brown explained. Green lasers in particular are close to the wavelengths that birds best perceive in motion, and the beams likely interact with the green chlorophyll in plants to produce disorienting effects only birds can see.

Although the research is limited, Brown continued, it’s promising. Her own study found that lasers could reduce bird damage on corn by up to 70 percent, while Dutch scientists determined in 2021 that lasers cut wild bird visits to a free-range egg farm by over 98 percent. In a survey published in 2024 by Cornell University, corn growers reported that lasers were by far the most effective method of bird control, outpacing options like scare eye balloons and wacky inflatable arm-flailing tube men.

A notable gap in the data, says Brown, concerns whether lasers routinely damage birds’ eyes. A 2021 masters thesis from Purdue University found that the beams could induce cataracts, corneal swelling, and other problems in the lab, but no peer-reviewed study has yet checked their impacts in the field.

“I shined that laser directly at the head of the alpha goose, and my goodness, did they disperse instantly.”

As the scientific understanding matures, many growers are pressing ahead with lasers based on their own experiences. Among them is Jake Vlaminck, general manager of turkey producer Fahlun Farms in Lake Lillian, Minnesota, about 100 miles west of Minneapolis.

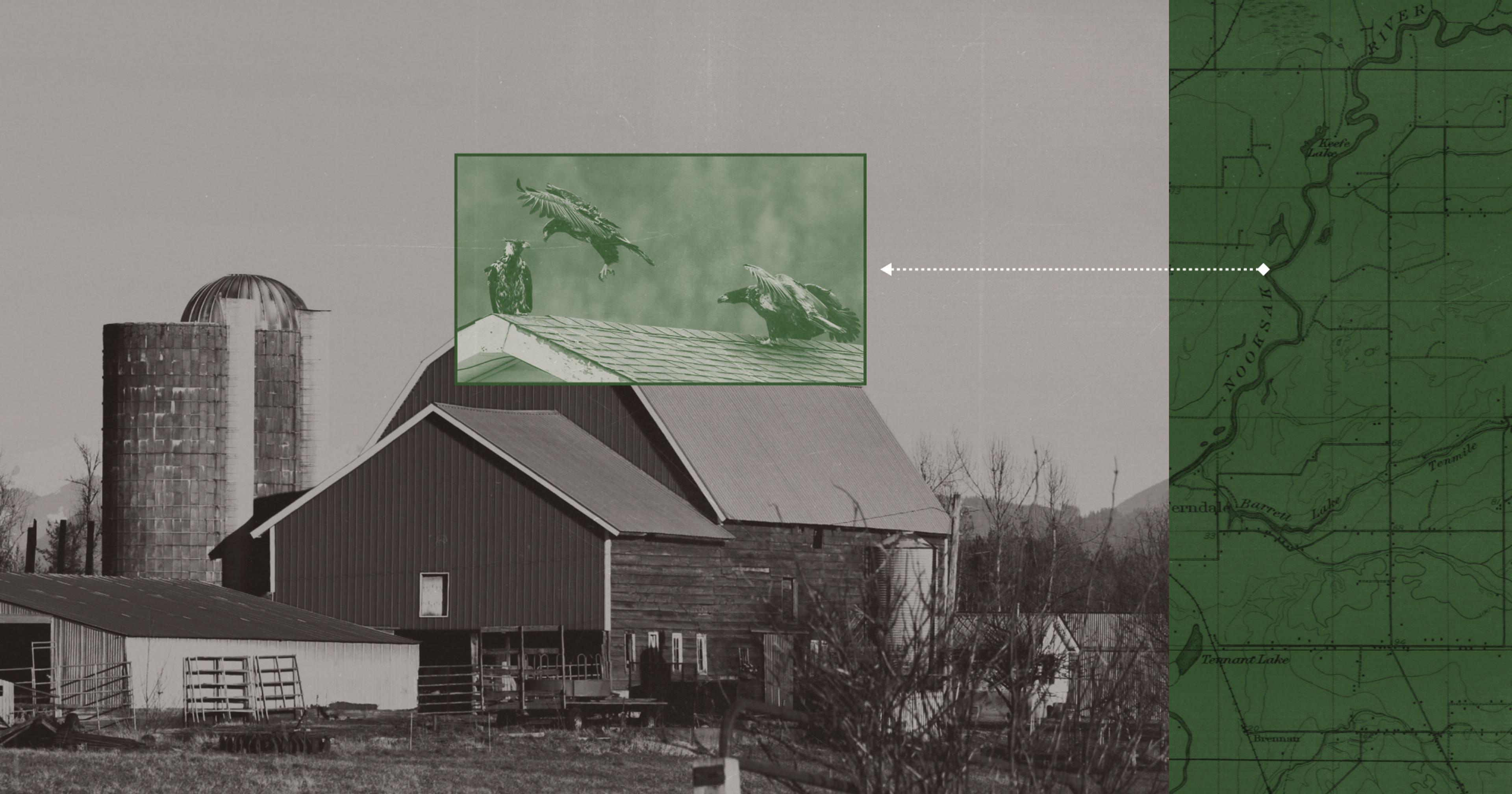

The town’s namesake lake and other nearby bodies of water attract a lot of gulls, Vlaminck said, that proceed to roost on the roofs of his barns. He didn’t give them a lot of thought until 2022, when a bird flu outbreak forced him to cull tens of thousands of turkeys. Realizing that gulls or other wild birds might have introduced the flu, he started looking for countermeasures.

A neighboring farmer encouraged him to attend a demonstration of the Bird Control Group’s AVIX Autonomic, a robotically controlled system that costs about $15,000 to purchase and install. Its laser swivels on a base to target dozens of different points in constantly shifting patterns, keeping birds from growing accustomed to the beams.

Although Vlaminck remained a bit skeptical, he was willing to take a chance on anything that might avoid a repeat outbreak. He set up two units in early 2023, before the spring migration season, and over the following year his flocks remained untouched by flu.

“It really got me interested in saying, ‘This must be the answer here,’” said Vlaminck. He’s since bought two more lasers to cover even more of his farm, and as president of the Minnesota Turkey Growers Association, he’s become something of an evangelist to other farmers. Minnesota is now a hotspot for laser installations; poultry farmers have put in over 100 laser systems since 2023, some with support from a state program meant to prevent bird flu transmission.

Federal authorities, however, aren’t as enthusiastic. U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins announced a $1 billion strategy to combat bird flu in February, including $500 million in cost-share funding to help farmers beef up their biosecurity. But the USDA is unlikely to approve lasers as part of that plan.

Agriculture Brooke Rollins announced a $1 billion strategy to combat bird flu in February, but the USDA is unlikely to approve lasers as part of that plan.

“While we cannot speak to all possible recommendations that will be made or mitigations that will be considered for the cost-share program, we can say that lasers have not been proven to deter the types of wild birds most commonly found around poultry facilities,” wrote Tanya Espinosa, a spokesperson for the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

(Other segments of the federal government appear less worried about the disease. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, overseen by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., recently paused efforts to increase bird flu testing. Kennedy has also suggested poultry farmers let the flu spread freely through their flocks, an idea experts say would be both inhumane and a likely economic disaster.)

Vlaminck argued that the USDA’s position ignores lasers’ demonstrated potential. He compared recent cases of bird flu in Minnesota poultry to those across the U.S. as a whole: The country saw 21.8 million cases in 2023 and 50.7 million in 2024, an increase of over 130 percent, while the state’s caseload rose just 14 percent over the same period. “I don’t know what better study you could have than to look right there and say, ‘What did Minnesota do differently?’” he said.

Even without federal backing, farmers are moving forward with the technology. Keith Gutshall is a 20-year veteran of the pest control industry and owner of The Fur Bandit in central Pennsylvania. He started installing lasers just two years ago, but he estimates they’ve already grown to about 40 percent of his business, with agricultural clients including major egg producer Hillandale Farms and multiple dairies.

Lasers aren’t a silver (or shiny green) bullet, emphasized Gutshall. They work by line-of-sight, so they can be a poor fit for facilities with complicated layouts, and growers may be constrained by nearby roads or airports where lasers pose a safety hazard. Top-of-the-line systems are expensive and require careful programming to perform at their full potential.

But for farmers who’ve lost entire flocks to bird flu, or find their stockpiles of feed pecked apart, Gutshall says the investment can be very worthwhile. He estimates that laser clients usually see their wild bird activity drop by 80 percent, with even further reductions when they add on other deterrents. And the entertainment value can’t be underestimated.

“People that I show it to are amazed, and after doing this two years, I’m still amazed,” said Gutshall. “It’s actually kind of fun to watch the birds take off when the laser gets close to them.”