We’re living through the largest outbreak of avian influenza in U.S. history — the stakes have never been higher.

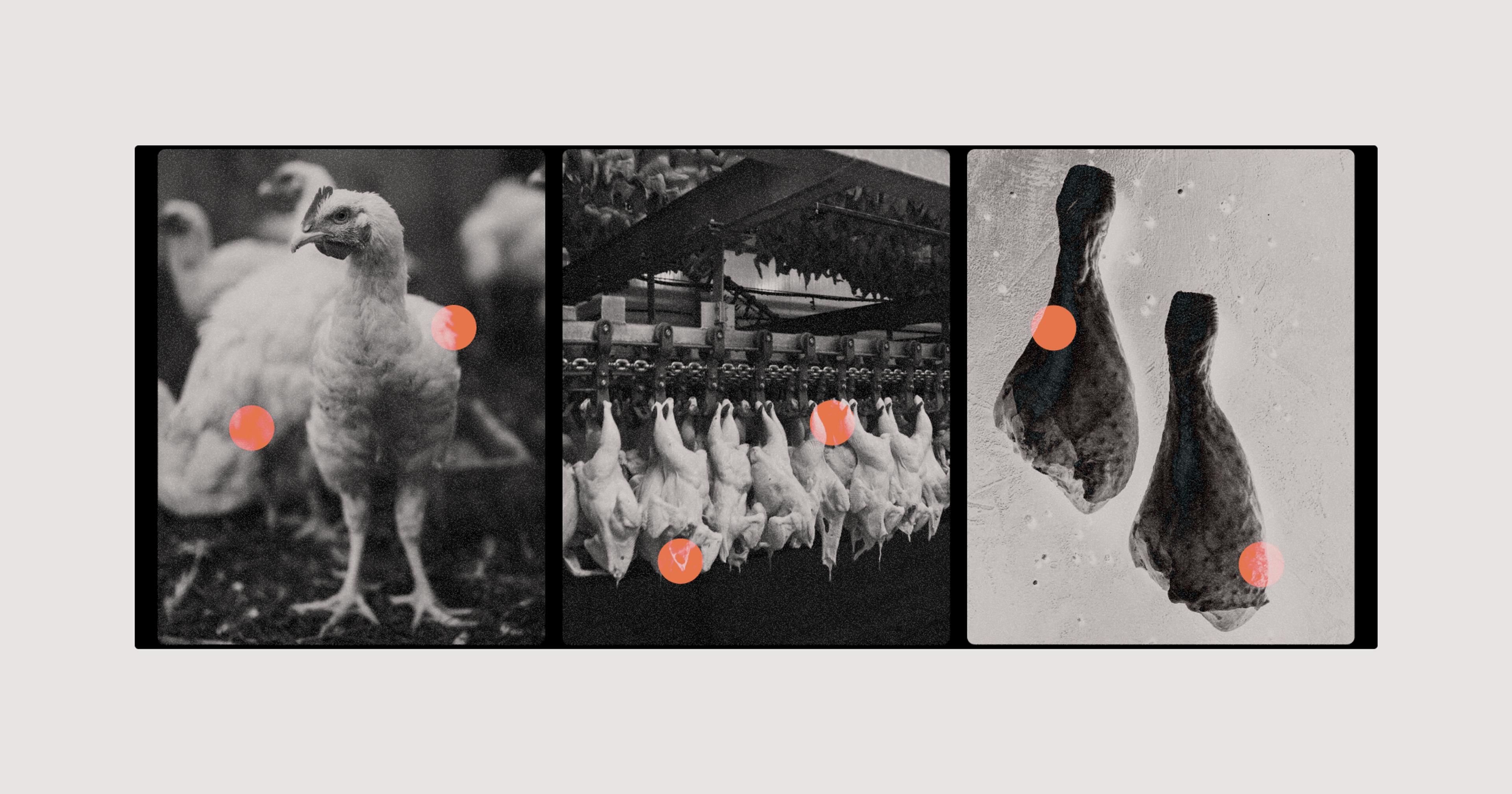

At last count, more than 58 million chickens, turkeys, and other birds have died in this year’s outbreak of avian influenza, the worst in our nation’s history. Globally that number is in the hundreds of millions. And beyond the staggering loss of life and significant trade disruptions, another fear looms large among infectious disease specialists — human contagion.

“My great worry is whether it will mutate so it can be transmitted human to human,” said Robert G. Webster, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis who has spent his career researching avian flu. “That would be a catastrophe — it would be worse than the 1918 flu.”

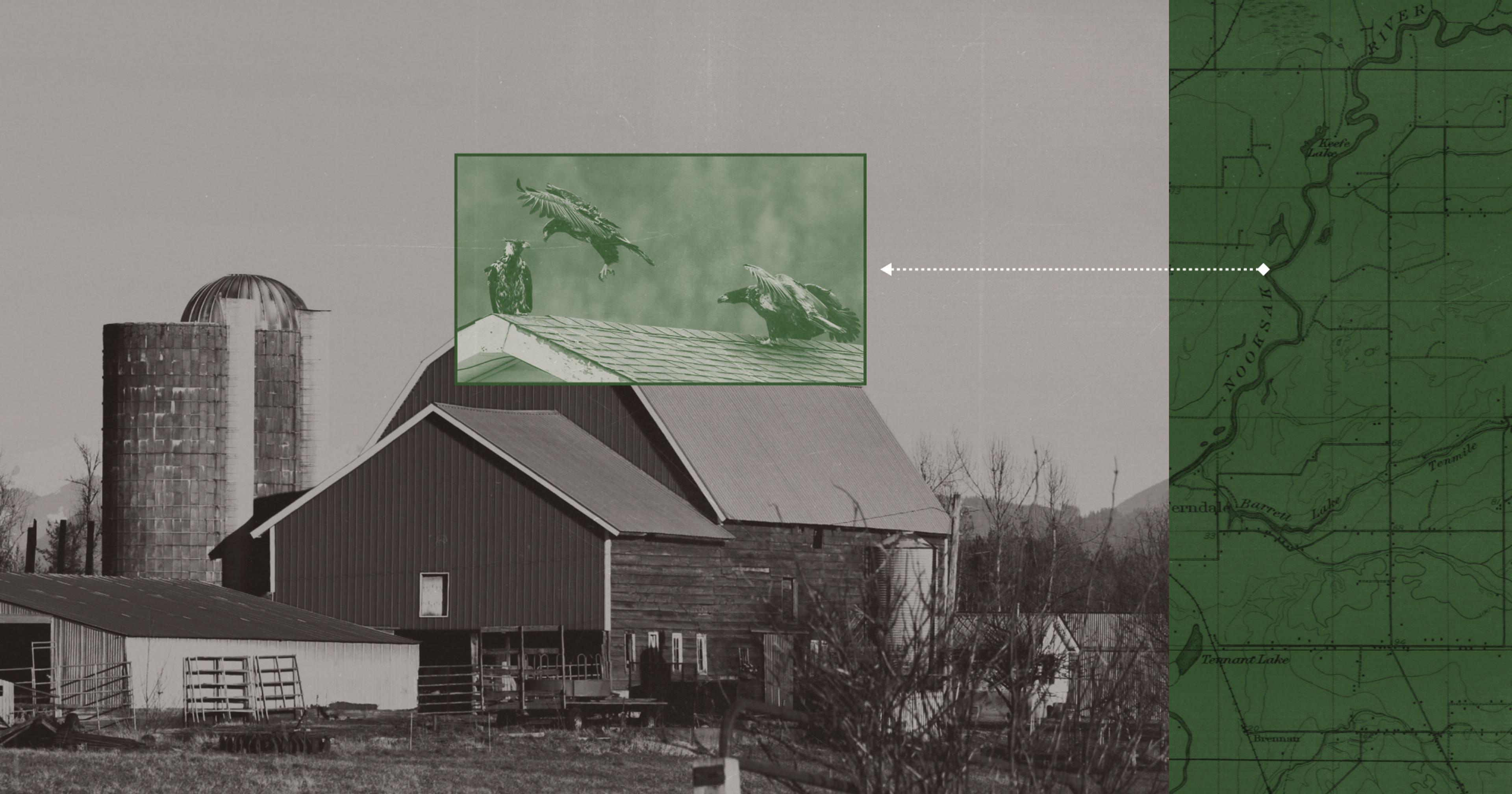

Many researchers would argue a catastrophe is already upon us. The most recent outbreak of highly-pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI, has been found in every state except Hawaii, and more than 70 countries around the world. Its spread has been rapid, and outside our livestock populations, it’s been killing wild birds — including endangered species like condors — which significantly hastens its spread. There was even one human death this year from HPAI, an 11-year-old girl in Cambodia. And, though the current outbreak appears to be winding down, there is a grim certainty we’ll be facing a new strain soon enough.

As with the global human pandemic we still haven’t really overcome, the word on many lips is “vaccination.” The White House indicated earlier this spring that this path is being seriously considered, while the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has been trialing multiple poultry vaccines on an expedited basis. Additionally, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) just kicked off a pilot vaccination program for condors in the wild.

But as much as a Pfizer quick fix might seem like the obvious solution, there are a host of practical hurdles standing in the way of a widespread vaccine program.

The virus that’s currently causing the global havoc is a particularly virulent strain of the notorious H5N1. It spreads bird-to-bird via saliva, feces, and nasal secretions, and has alarmed virologists by infecting a larger-than-expected number of wild birds and mammals, including foxes and bears. Eleven humans have been infected with avian influenza since December 2021, including one in the United States.

“This type of H5 has been around since the 1990s, so people have gotten used to hearing about it,” said Richard Webby, another bird flu expert at St. Jude’s. “I think that’s led many people to underestimate just how different the last 18 months have been with regards to [avian flu]. This isn’t like anything we’ve seen before.”

Yuko Sato, a poultry veterinarian and associate professor at Iowa State University, said we’ve learned a lot since 2015, the year of the biggest-so-far avian flu outbreak in the U.S. Commercial poultry producers heightened and streamlined their biosecurity protocols, the federal government fleshed out its own preparatory measures, and “everyone became much more well-versed in, you know, who is doing what, do we have the resources to do it, and what, exactly, are we doing?”

“I think it’s sort of pushing the ‘easy’ button for a lot of people. They know what a vaccine is, and they can relate to that.”

One thing we’re doing more this time around is seriously exploring vaccine options. There are currently several licensed vaccines (administered by shot) for avian flu, but it’s unclear how effective they will be against this current strain — if at all. As anyone who’s gotten a flu shot knows, what’s effective this year may be all but useless the next.

Samantha Gibbs, a wildlife veterinarian at FWS, is coordinating her agency’s condor vaccination efforts. This year, HPAI killed as many as 21 wild condors, an alarming figure considering there are fewer than 600 of them worldwide. Gibbs said the decision to attempt vaccination on condors makes sense in terms of protecting an endangered animal, but also because it’s a heavily monitored wild bird population. That means it will be easier to monitor the vaccine’s success rate — thus, whether it would be effective with our livestock and other birds.

Still, Gibbs takes a measured tone when discussing the vaccines — which were created for chicken populations — making clear that she thinks her work should have zero impact on global trade. “I think it’s sort of pushing the ‘easy’ button for a lot of people. They know what a vaccine is, and they can relate to that,” she said. “I would say they’re just one small piece of a much bigger pie in terms of preparedness and prevention. It’s not a silver bullet. We’re not even sure if it’ll work in the condors at this point.”

Currently, if H5N1 is detected in, say, a broiler hen facility, the typical response would be to “cull” all the facility’s birds and dispose of the bodies — essentially a mass slaughter event. Though many chicken deaths have directly resulted from avian flu, this culling is responsible for the global six-figure bird death numbers since last October. “If an industry can only remain by culling millions of animals it is not sustainable,” Arjan Stegeman, professor of veterinary medicine and epidemiologist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, told The Guardian. That’s a big reason why researchers are working so fast to develop effective H5N1 vaccines.

When it comes to vaccinating domesticated poultry populations, further complications emerge. Most countries will not import vaccinated birds, though the logic is a bit convoluted. Essentially, because it would be harder to detect whether a vaccinated bird is an H5N1 carrier, countries are wary of taking the risk that vaccinated imports will infect their native poultry populations. You could call it an abundance of caution.

“Right now I think a lot of places are operating out of fear. And nobody is going to drop their objections unless we do it first.”

For this reason, the National Chicken Council has vocally opposed vaccinating domestic chickens — the council predicts billions in export losses, and the loss of 200,000 farm jobs. (The U.S. Turkey Federation does not oppose a vaccine, but is encouraging the federal government to develop new trade agreements with regards to vaccinated exports.)

Carol Cardona, Pomeroy Endowed Chair in Avian Health at the University of Minnesota, thinks the U.S. should start importing poultry from countries that currently vaccinate against avian flu — China, Egypt, and Vietnam are a few examples. “Right now I think a lot of places are operating out of fear,” she said. “And nobody is going to drop their objections unless we do it first.”

For now, it’s something of a moot point, as an effective vaccine has not been developed against this strain of H5N1 — though USDA announced preliminary results of their vaccine tests this week. Researchers looked at two commercially available vaccines and two they had developed in-house, all of which had positive preliminary results. That said, a USDA spokesperson told us, “USDA continues to estimate an 18-24 month timeline, under a best case scenario, before having a vaccine that matches the currently circulating virus strain, available in commercial quantities, and that can be easily administered to commercial poultry.”

Webster, who has been referred to as the “pope of avian flu,” points out that if and when a good vaccine is developed, it will need to be regularly updated to combat new strains, much like the flu or Covid. Cardona adds, “We now have the disadvantage and the advantage of knowing that next spring, we’re going to see the same clade of viruses. Now we’re confident it’s going to be this same [HPAI] again and again and again.”

And of course, the urgency of developing a vaccine is exacerbated by the looming specter of human-to-human transmission. The World Health Organization points out that this has never occurred, but considering there have been 875 human cases of H5 bird flu since 1996, some researchers think it’s only a matter of time. Webster, who has called eventual human-to-human transmission “inevitable,” said he’d like to see a greater sense of urgency in the general public.

“I think there’s an attitude like, ‘This virus has been wrapped for 30 years, so why are we getting our knickers in a twist at the moment?’” he said. “But consider the fact [the virus] acquired the ability to spread throughout the whole world and that hadn’t happened before. I think we need to be ready for anything.”