Millions of male chicks are killed, needlessly, every year. The tech sector is ready to act, but is the egg sector ready to change?

Let’s start with some grim news: Every year in America, approximately 300 million male chicks are gassed, ground up, and disposed of, simply because they don’t lay eggs.

America’s poultry industry is divided by production type. Egg producers raise egg-laying hens and meat producers raise meat birds, also called broilers. In the broiler cycle, both male and female birds are used for meat production. Yet, in the egg-laying cycle, only female birds are required.

Male chickens are considered an egg-industry byproduct; egg producers currently don’t have the resources, or infrastructure, to grow and slaughter for meat. Thus, male chicks are culled en masse, often only a few hours after birth.

It’s a controversial practice that pulls the heartstrings of consumers who know of it. However, according to a new survey by Silicon Valley think-tank Innovate Animal Ag, most Americans have no idea this is going on.

Run by former Google engineer Robert Yaman, with a communications arm headed by former political pollster Sean McElwee, Innovate Animal Ag found that only 11 percent of U.S. consumers know that male chicks are culled immediately after hatching. Another 48 percent believe that male chicks are raised for meat, a practice uncommon in the U.S. — at least when they are hatched from laying hens.

The numbers suggest a serious disconnect between consumer beliefs and industry practices — one Silicon Valley is looking to fix. The hope is that male chick culling can be reduced or eliminated by adopting new technologies, such as in ovo sexing.

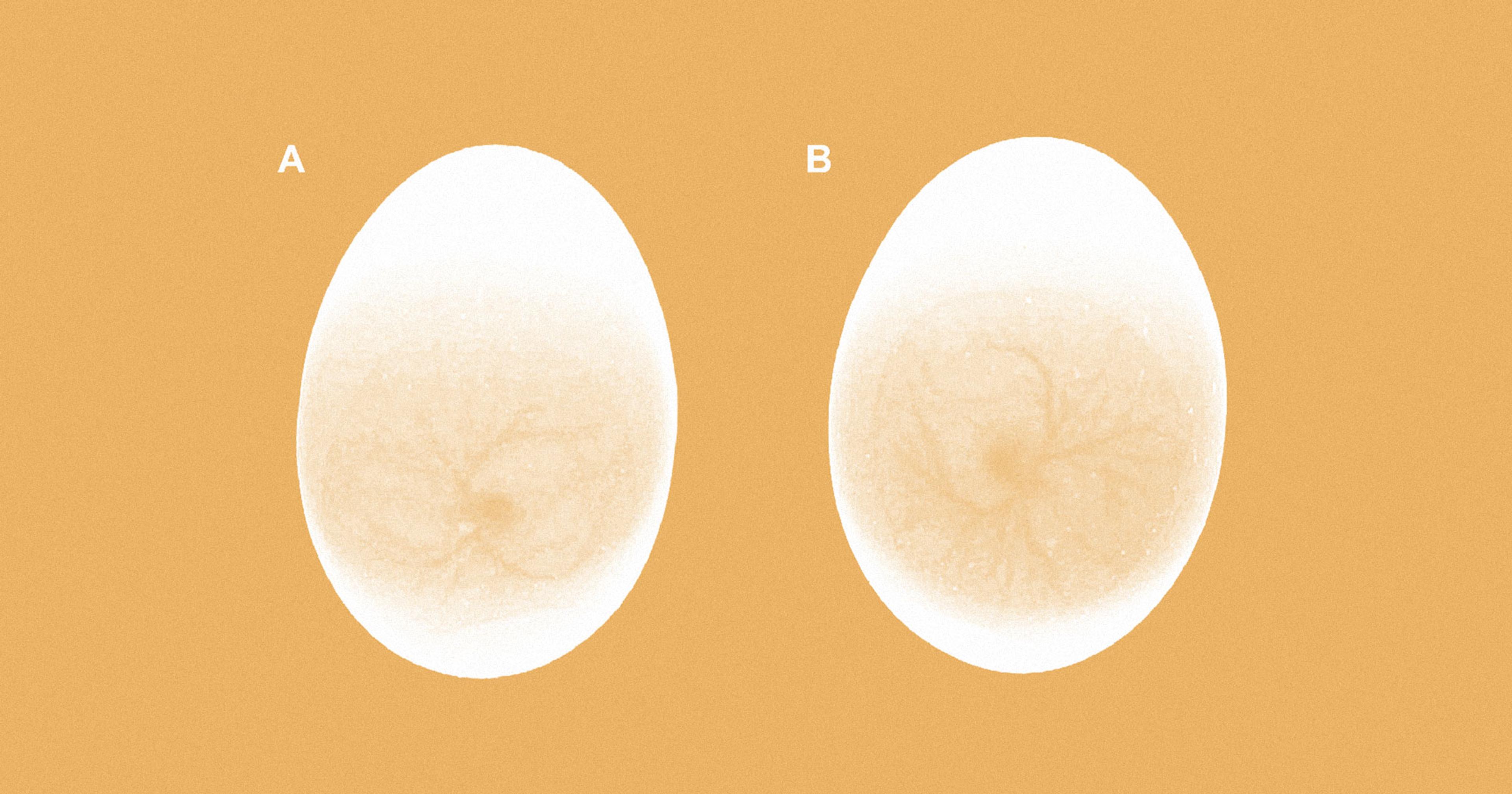

In ovo sexing is a process in which the sex of the chicken embryo can be determined while still inside the egg. This enables producers to identify and sort eggs before incubating, eliminating the need for culling altogether.

The technology is already being used in Europe, a response to countries like Germany, France, and Italy banning chick culling in recent years. In ovo sexing has also been adopted by the largest hatchery in Norway, Steinsland & Co., independent of any government mandate.

Unsurprisingly, America is still dragging its feet. Though the United Egg Producers (UEP) called for the elimination of male chick culling in 2016, U.S. egg suppliers have yet to discard the practice. UEP said in a 2021 press release that its members have been committed to research and development in the field.

“I think oftentimes the conversation when it comes to animal welfare can be very zero-sum. It can be, either we make more money, or we do this welfare intervention.”

According to data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), 631.7 million egg layers are produced annually, which would equate to the same number of eggs needing to be sexed. By contrast, Respeggt, the company behind the in ovo sexing technology Steinsland uses, has only sexed about 20 million eggs collectively, in Norway and Germany.

The lack of progress is concerning, especially for groups vying for change. Innovate Animal Ag’s survey found that consumer sentiment largely favors a shift towards more humane egg-production practices, with 61 percent of buyers uncomfortable with male chick culling and 73 percent agreeing that the egg industry should find an alternative.

Yaman and McElwee are looking to use the Silicon Valley ethos of innovation and scale to encourage the U.S. to follow Europe’s lead. They want the industry to see the business incentive in adopting in ovo sexing technology. This includes increased profits, as consumers demand more “humane” eggs.

“I think oftentimes the conversation when it comes to animal welfare can be very zero-sum,” Yaman, who previously worked in the cultivated meat sector, said. “It can be, either we make more money, or we do this welfare intervention. And, as a result, those conversations can be very antagonistic.”

“In the U.S., there’s such a robust consumer base of folks that are willing to pay a premium for better welfare practices,” he continued. “That sort of strategy, I think, is possible for a number of agricultural technologies, including in ovo sexing.”

“In the U.S., there’s such a robust consumer base of folks that are willing to pay a premium for better welfare practices.”

Innovation in the field does seem to be picking up pace. This year, researchers at the University of California published a study claiming to be able to tell the sex of an egg through a mass spectrometry sniff test. Agri-AT, an ag-tech company based in Germany, also invented a machine that uses noninvasive imaging to look inside the egg. The machine can determine the sex by day 13. Agri-AT’s technology is currently in use in hatcheries across Europe.

Yet, in April of this year, the $6 million Egg-Tech prize — aimed at advancing technology related to egg sexing technology — went unclaimed. Yaman said the prize was focused on “noninvasive solutions, and non-gene editing solutions,” that “worked early in incubation, before day seven.”

“Since then the science around chicken embryos has advanced, and [that criteria] is no longer the right threshold, in my opinion,” said Yaman.

Still, in ovo sexing isn’t the only way to stop the practice of male chick culling. There’s also the possibility of integrating the egg and broiler industries — at least on a smaller scale — and raising male chicks for meat. Kipster is a Dutch-owned farm that raises male and female chickens without sexing or culling. Kipster has three farms in the Netherlands, and one in Manchester, Indiana.

Ruud Zanders, a Kipster co-founder, said one of the main reasons industrial egg producers don’t use rooster meat is because they don’t get as big and meaty. In other words, they make less profit.

If farms can spend less money on manufactured feed, then raising additional birds for meat — i.e., roosters — may not seem like such a hefty investment.

Yet, Zanders said if farms can spend less money on manufactured feed, then raising additional birds for meat — i.e., roosters — may not seem like such a hefty investment. Kipster raises all of its chickens on food waste, rather than traditionally manufactured grain feeds. This includes bakery waste, fruit and vegetable pulp, coffee grounds, and more. “We only feed them things that we cannot and do not want to eat anymore as humans,” Zanders said.

Critics also argue that roosters are generally more aggressive, prone to pecking hens until they are injured or distressed. Consequently, they are often unwelcome at egg-producing farms. Zanders said Kipster farms are full of enrichment activities, such as pecking blocks and alfalfa hay bales to discourage this behavior.

In ovo sexing wasn’t available when Zanders started Kipster. And, either way, he said, his farm’s ethos extends beyond simply eradicating chick culling. They want to improve animal welfare in the poultry industry as a whole. Stopping the conventional broiler production cycle is an important part of Kipster’s wider farming mission.

While it’s easy to think a single, technological solution can turn industrial animal agriculture on its head, reality isn’t always so simple. Zanders said, “In my view, [ovo sexing] is a technique that lets the world go on with what we’re already doing.” He added, “I think we have to change the whole system.”

Indeed, while ovo sexing might save male chicks in the present, the life of those chicks in industrial farms remains controversial. Many states still use battery cages to produce eggs. Cramped and unsanitary, these conditions are prone to disease and suffering.

For Yaman and McElwee, welfare-focused agtech has the potential to be the next solar panel, or the next Tesla. “Ultimately, I feel like [ovo sexing] technology has a lot of potential to shift the paradigm and find solutions that are good for everybody. Good for producers, good for consumers, and good for animals,” Yaman said.

Whether this approach to improved poultry welfare can scale or not remains to be seen. For now, in ovo sexing is just another promising idea waiting to hatch in America.

Correction: An earlier version of this story implied the egg company Steinsland was conducting in ovo sexing itself. The earlier text also said 10 million eggs had been sexed in Norway and Germany, when the actual number was roughly twice as high.