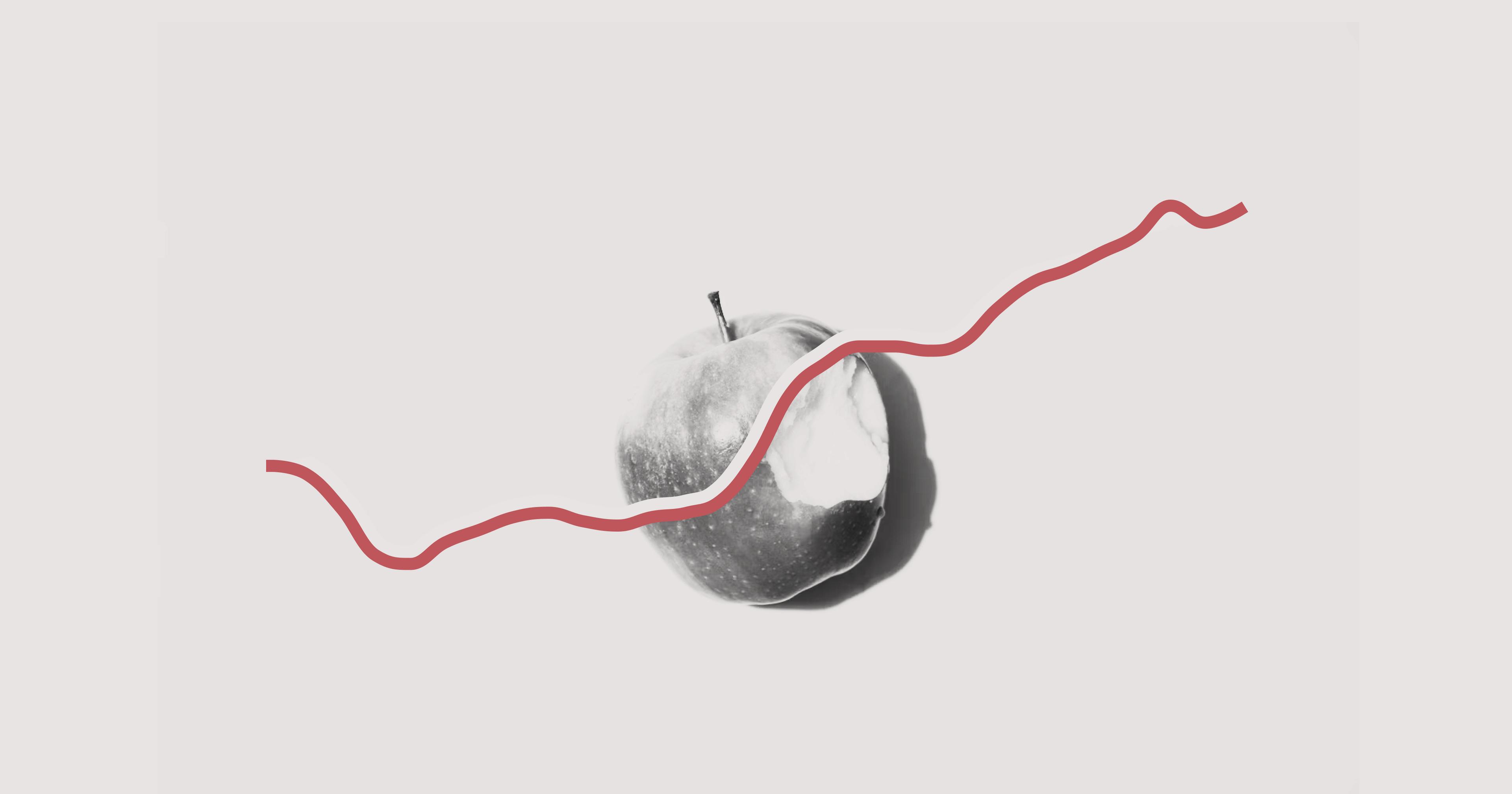

And what’s been driving them up in the first place — Inflation? Disease? Supply and demand? Price gouging? Yes.

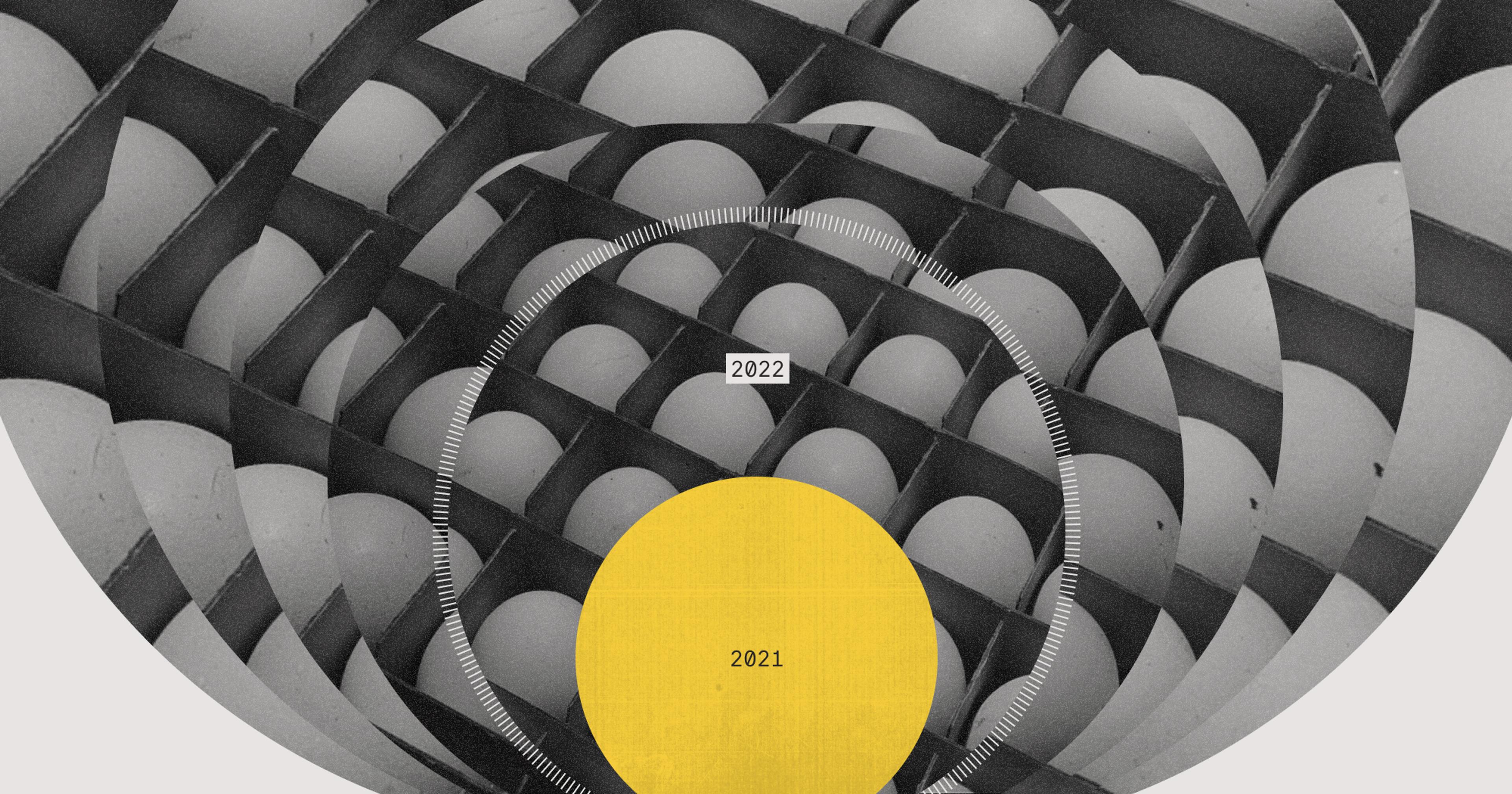

According to figures from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, eggs were one of the single most inflationary items in the entire country in 2022, ending the year with a full-year inflation rate of 32%. Electricity rose less than half as much at 14%, housing costs only 7%, and new cars — whose supply was famousimperiled by chip shortages — grew a paltry 6%. Egg prices, on the other hand, have been rising so fast that it’s not uncommon to see grocery stores with blank stickers where the price should be, like retailers don’t really know what they’re worth — or they don’t want to put up a label that they’ll just need to change tomorrow.

Records have been broken: December 2022 saw the highest wholesale egg prices ever recorded, according to the monthly Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Outlook report from the USDA’s Economic Research Service. They averaged $5.03 per dozen, 247% higher than they were in January of the same year, peaking at $5.40 the week before Christmas. In some areas the increase was even higher — these already-high numbers mask substantial regional variation. In New York, it’s not unusual to see a dozen eggs for $9.99 or more; a Massachusetts restaurant owner told PBS Newshour that his egg costs were up 220% from the previous year.

What’s causing this spike? According to many experts, it’s a perfect storm of several factors impacting all at once — higher costs to producers and a disease-driven decline in chicken populations, hitting at a time of high overall inflation, all for an increasingly popular staple product.

Egg producers have said their input costs have risen across the board, contributing to high consumer prices. Emily Metz, president and CEO of the American Egg Board, told the Associated Press in a recent interview that feed costs for farmers were up as much as 60%, and “labor costs, packaging costs — all of that ... those are much much bigger factors than bird flu for sure.” A USDA report found farm wages rose by 7% in 2022.

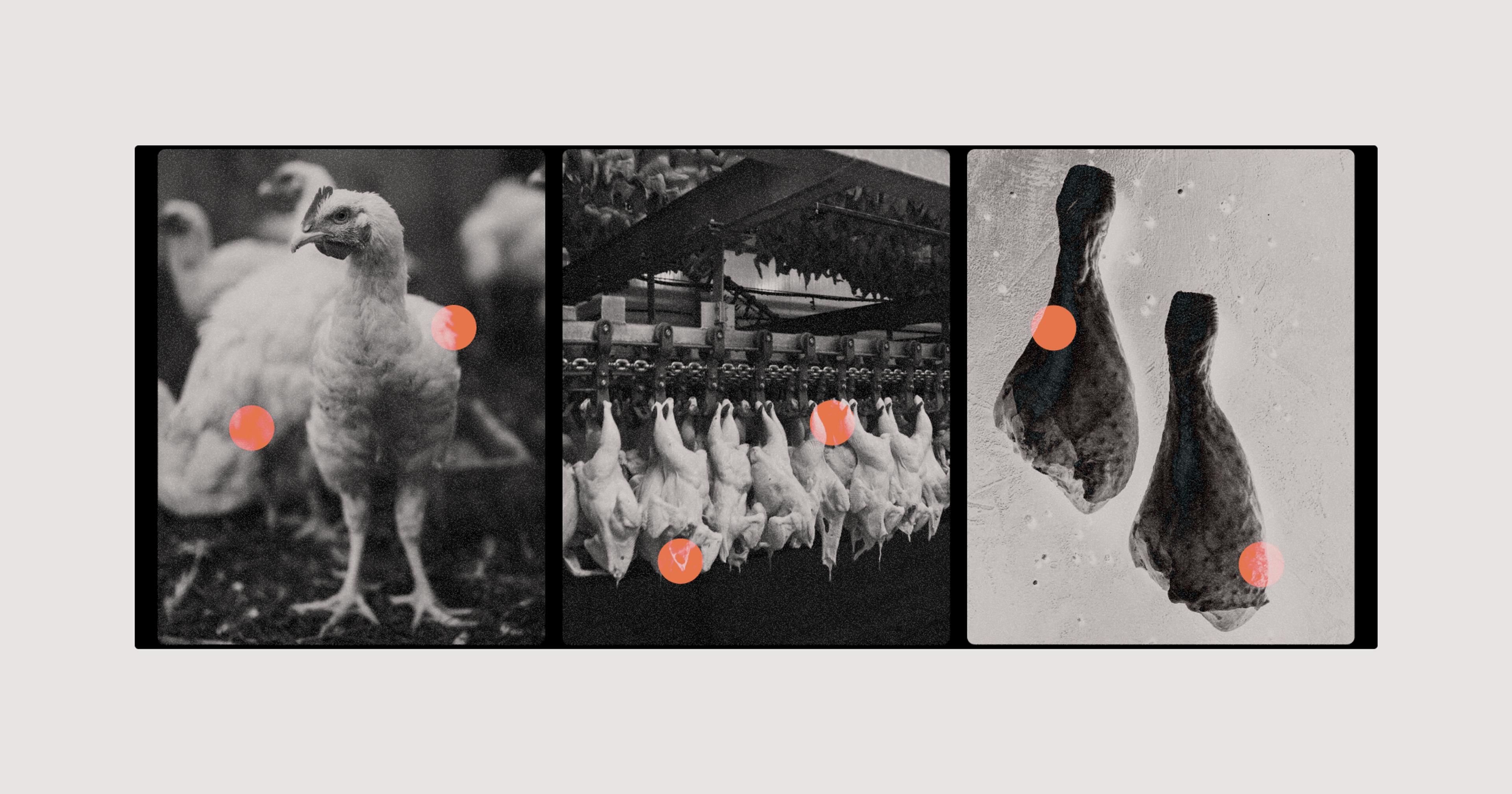

Beyond basic inflation, you’ve likely heard that the U.S. has had a large decrease in its chicken population thanks to an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza, or avian bird flu. By the end of December 2022, the disease had killed more than 43 million birds, or around 11% of all egg-laying hens in the country. According to a report from the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), this caused December 2022’s egg production to drop 6% year-on-year.

Eggs are also a classic case of what economists call inelastic demand, meaning demand stays relatively stable even with large changes in price. It also means that a dip in supply, even just a small one, can have dramatic ramifications on price and availability, because the same number of people still want the same number of eggs (though of course some consumers end up getting priced out). Suddenly, there simply aren’t enough to go around, which can cause empty shelves and skyrocketing prices.

Speaking of demand, the holiday season is also traditionally the time of year with the second-highest demand for eggs (Easter is first), which are a key ingredient in both holiday baking and big family breakfasts. The increased demand coming during a time of lowered supply — while the country was also suffering record inflation — was too much for the market to bear.

“Farmers don’t set the price of eggs — the market does.”

“You have three factors that hit at the right time that have caused prices to go up,” said Benjamin Campbell, an associate professor in the University of Georgia’s CAES Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics. “You had supply going down, you had demand going up, and you had input prices going up as well. So you had three things just hit the system and prices went sky-high.”

In a prepared statement shared by Center Fresh Group (the country’s seventh-largest egg supplier), the American Egg Board wrote, “Farmers don’t set the price of eggs — the market does. Volatility and uncertainty because of inflationary pressures and the continued impacts of bird flu have disrupted the egg market, which results in higher egg prices.”

Still, not everyone is convinced that these price spikes can be explained by simple market forces. Indeed, not all egg producers have raised their prices.

Dan King owns and operates New York’s Rexcroft Farms along with his brother Nate. Rexcroft has about 400 hens laying 230 to 260 dozen eggs per week, all of which they sell at a single Brooklyn farmers’ market.

“The whole egg price situation, it’s frustrating,” King said. “We’ve all had some increase [in costs], and if prices went up 10, 20, even 30%, okay, I could see that. But these prices doubling or tripling? It doesn’t make sense.” King is still selling a dozen eggs for $6 (a bargain in New York City), in part for philosophical reasons. “Eggs are an inexpensive protein,” he said, “and that’s what a lot of people rely on. I wasn’t going to jack the price up just because my costs have gone up a little.”

“I wasn’t going to jack the price up just because my costs have gone up a little.”

In recent weeks, some politicians and lobbying organizations have been pointing the finger at major egg suppliers, who they accuse of doing just that — unjustly increasing prices. Indeed, there’s a precedent for behavior like this. In 2018, a jury found several large egg producers guilty of a conspiracy to limit production and drive up prices.

Advocacy organization Farm Action recently sent a blistering letter to Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chair Lina Khan, alleging a “collusive scheme among industry leaders” to “extract egregious profits reaching as high as 40 percent.”

Another consumer group, Groundwork Collaborative, agrees with Farm Action. Rakeen Mabud, its chief economist and managing director of policy and research, said that egg producers are using “the excuse of avian flu, alongside their market power, to rake in record profits on the backs of consumers.”

Senator Jack Reed (D-RI) has written his own letter to the FTC, asking it to “open an investigation into potential price gouging and other deceptive practices by the country’s largest egg companies.”

Many of these allegations center on Cal-Maine foods, by far the largest egg producer in the country, controlling 20% of the U.S. egg market with 70% more hens than its closest competitor. At the end of November 2022, Cal-Maine reported that its year-on-year profits had gone from $50 million to $535 million, a tenfold increase. According to a January 2023 investor presentation, during the same period its production costs only rose 20%.

Egg producers are using “the excuse of avian flu, alongside their market power, to rake in record profits on the backs of consumers.”

Cal-Maine didn’t reply to Ambrook’s requests for comment but told the Associated Press in late January that the “domestic egg market has always been intensely competitive and highly volatile even under normal market circumstances,” and it is “doing everything we can to maximize production and keep store shelves stocked.”

For now, several indicators show the crisis somewhat abating, though it’s unclear if the avian flu crisis is even over yet. Deaths ping-ponged through the end of the year from 4.9 million in September to 1.1 million the very next month; December deaths were 3.9 million. And avian flu has continued to spread around the world, even sparking concerns of a jump to humans as it began spreading between other mammals. At the same time, egg production is making a fitful recovery, though still lagging behind 2021 levels. And wholesale prices are down, too, with January’s average of $4.12 more than a dollar lower than December’s. For these reasons, some experts see a retail price decrease on the horizon, though we haven’t gotten there yet.

“Now we’re rolling into Easter, which is one of the biggest egg demand times,” said Campbell. “My expectation is that we’re going to see prices stay relatively high for the first quarter until we get through some of the Easter season and we get down for demand. And then once we get some birds back in the system, you’ll start seeing prices come down.”

The USDA agrees. Though it’s been revising estimates upward as prices continue to stay high, it’s currently projecting a nearly 30% drop between Q1 and Q2 2023, roughly after Easter. It’s projecting the average price for 2023 will be 30% lower than 2022.

“Prices will come down,” said Campbell. “It’s just a matter of time.”