Farm radio is going strong after over a century on the airwaves. Is it ready to face the challenges of the future?

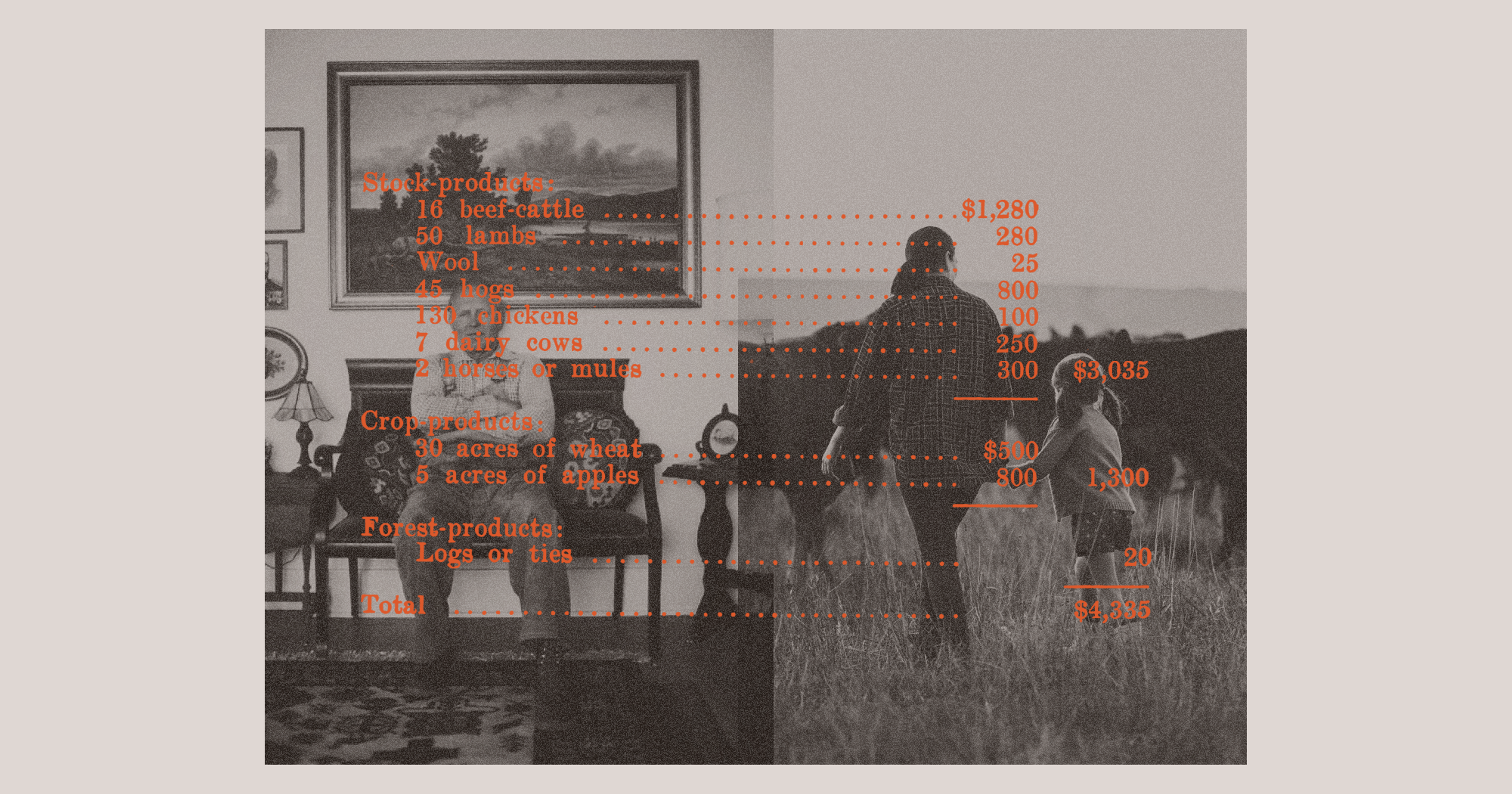

Each weekday morning, Jeff Ishee enters his home studio in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley at 6 a.m. to begin producing farm reports. Since 2002, Ishee has run On the Farm Radio, a one-man operation that distributes 11 daily reports of one to eight minutes in length to 95 stations east of the Mississippi River, representing more than 5 million listeners, including at least 430,000 farming operations.

“I try to put myself in the position of being in between the farmer and the consumer,” he said. “What’s available at the farmer’s market this week? Is sweet corn still in season? Can you buy locally produced watermelons in Western North Carolina?”

Farm radio has been part of commercial radio from its earliest days. Only four months after KDKA in Pittsburgh made history on November 2 by broadcasting live updates on the 1920 presidential election, Illinois grain dealer James Bush began broadcasting market prices under the call sign WDZ.

Even though terrestrial AM/FM radio now faces a lot of competition from podcasts, satellite radio, and streaming services like Spotify, statistics show that large numbers of people still tune in. According to Nielsen Media Research, 82 percent of Americans aged 12 and older listened to radio every week in 2022 — down just 10 percentage points from 2009. Further, 83% of farmers with at least $100,000 of gross farm income listened to farm radio five days per week or more in 2023, according to a National Association of Farm Broadcasters survey.

That doesn’t mean the content and technology of farm radio has stayed static, or that the medium doesn’t face challenges in a digital world. But Ishee still finds radio’s staying power impressive.

“The station that I started with, WSVA, they went on the air in 1935. That means that next year they will be celebrating their 90th anniversary,” he said.

“I’m really amazed that radio has lasted as long as it has.”

Accessible, Credible News

Amy Biehl-Owens, general manager for KRVN (880 AM) in Lexington, Nebraska, loves telling the origin story of the station and the Rural Radio Network, a farmer- and rancher-owned cooperative. After the historic winter of 1948-49 killed an estimated 20 people and thousands of livestock across the state, Nebraska’s Farm Bureau, Cooperative Council, Farmers Union, and Grange wanted to ensure farmers would never again be blindsided by severe weather. Traveling door to door, they sold $10 certificates of ownership until they raised enough money for a station.

Since KRVN’s first broadcast in 1951, the RRN has expanded to 15 stations across the state and over 3,000 owners who now pay $25 for a lifetime membership. Rather than paying dividends, Biehl-Owens said, the money goes back into running the stations. Beyond their robust farm reporting, the RRN works with local TV affiliates and newspapers to cover everything from high school football games to local and state government in both Nebraska and other states, from Kansas to Wyoming.

Radio has retained its popularity in the Corn Belt because much of the region lacks high-speed internet. “If you consider that agriculture is the biggest industry in a not very densely populated state, it makes sense that farm radio would be pretty much king out here,” Biehl-Owens said.

Credibility is another reason that farmers keep tuning in. The 2023 NAFB survey found that 76% of farmers highly trusted farm radio to provide credible and timely information. “We do have a much higher trust rating than general media — significantly higher,” said Sabrina Halvorson, national correspondent at AgNet Media, which serves California and multiple Southeastern states.

But she finds that trust is more easily cultivated by the farmers who listen than general interest listeners, who harbor concerns — sometimes spurred by misinformation — around topics like GMOs. “It’s important to me to have their trust as well,” Halvorson said.

Changing Trends in Storytelling

When Ishee got his first farm radio job, the retiring farm news director, Homer Quann, gave him some advice. “He said, ‘Ish, farmers want to know three things. They want to know the weather, they want to know market prices, and they want to know what other farmers are doing,’” Ishee said. Nowadays, “they can get the first two items on their smartphone, 24/7, instantly. The third thing they cannot get. So that’s what I’m trending toward.”

As an example, he highlighted his coverage of the opening of the Shenandoah Valley Produce Auction in 2005 helped show the predominantly livestock farmers in the area a way they could diversify their offerings.

On the opposite coast, Halvorson has noticed a growth in popularity in sustainability stories since she began working at the company in 2012. Policy and trade, including stories about shipping since supply chain issues that began during the pandemic, have also been popular.

No matter what the story is, however, it’s likely delivered in a shorter report than in the past. It’s easy to blame shorter attention spans, but Ishee also noted that station scheduling is a factor. Often, radio stations will have dead air they’re looking to fill near the end of the hour, Ishee said, and his one- to three-minute segments fit the bill. “We have some radio stations that play our reports, not only once a day, but sometimes three or four,” he said.

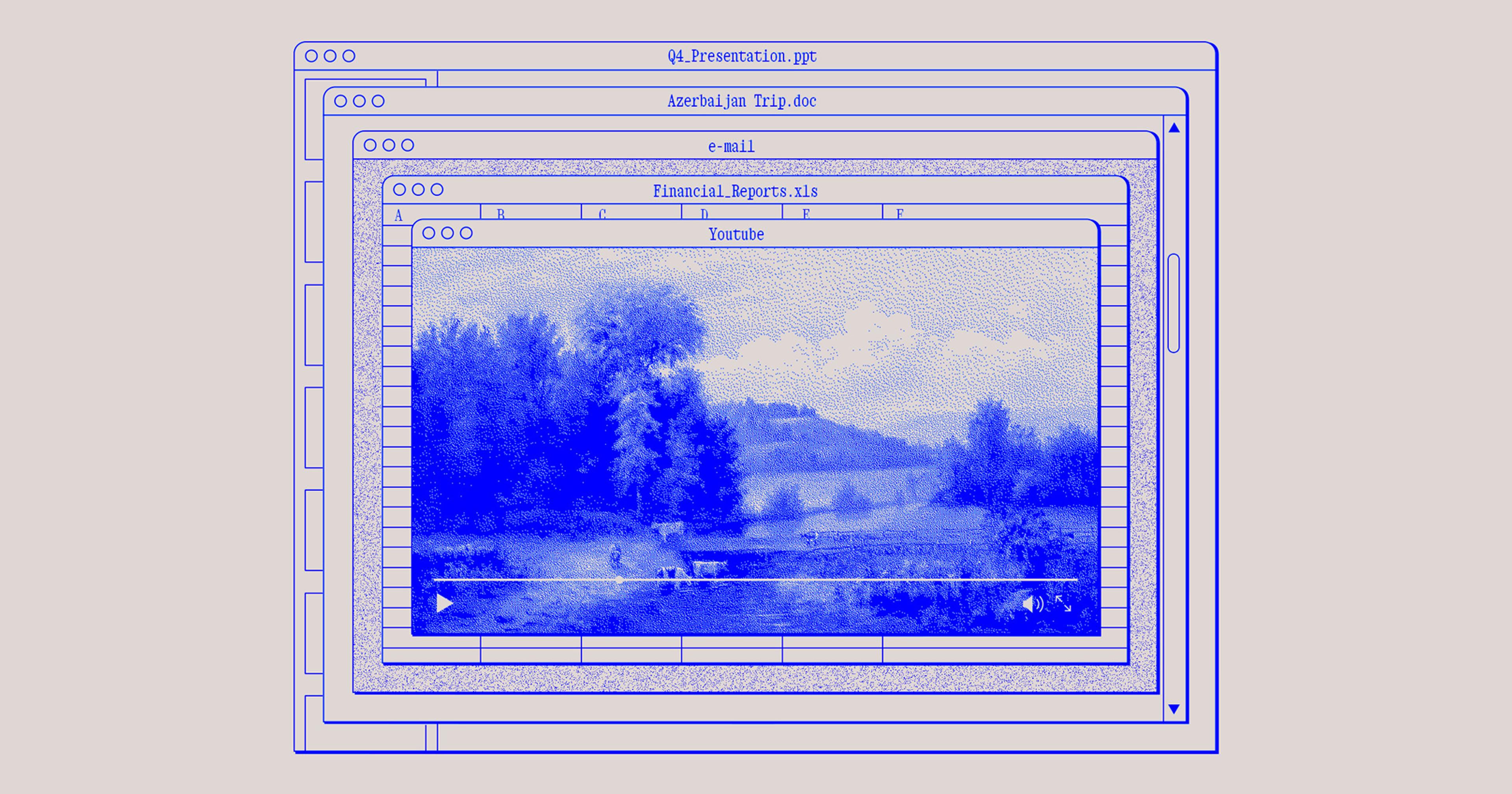

For longer form stories, podcasts are now the usual format. Ishee hosts a podcast called 4 The Soil that focuses on the importance of soil as a natural resource, and Halvorson has hosted AgNet Weekly, a deeper dive into legislative and policy. (The podcast is on hiatus due to Halvorson’s workload.)

Challenges Ahead

But as popular as podcasts are — “I see new podcasts pop up every day in agriculture,” Halvorson said — producing the next generation of traditional farm broadcasters might be a challenge.

“As far as I know, I’m the only remaining farm broadcaster in Virginia,” said Ishee. The younger people he has spoken to about farm radio as a career tend to want to make more money straight out of college, though he pointed out that “our revenue has gone nothing but up over the years”.

Halvorson has found a similar resistance in California, where many young people she encounters join high-paying ad agencies. “If you’re working at a small radio station, and you’re their farm broadcaster, it’s not an easy way to live,” she said.

The Rural Radio Network is once again an exception, thanks to a robust intern pipeline through multiple universities in Nebraska, as well as Oklahoma State and South Dakota State University. According to Biehl-Owens, at least four of KRVN’s current full-time staff interned at the station.

“We grow our own,” she said.

That said, even Biehl-Owens is noticing a shortage of some vital jobs like broadcast engineers — a job that requires a complex set of skills. They are currently looking to partner with local junior colleges.

Another infrastructure-related threat to radio comes from the car industry, as carmakers including Ford, Mazda, and Tesla have either planned to or already removed AM radio from their vehicles. According to the NAFB survey, 73% of farmers listen to farm radio in a vehicle, with 89% listening through AM/FM stations. The NAFB has joined over 20 advocacy groups to support the AM in Every Vehicle Act to ensure that all passenger motor vehicles are equipped with AM radio. (The bill has sat idle in the Senate since September 2023.)

Changing Demographics, Changing Listeners

Even as the demographics of agricultural workers has changed, farm radio remains a very homogeneous space, according to Halvorson.

In the Willamette Valley of Oregon, however, Radio Poder provides a glimpse of a possible future direction for farm radio. Radio Poder broadcasts from Woodburn, a town of 26,013 residents in which 16,000 are Hispanic/Latino and 52 percent speak Spanish at home. Farmworkers make up not only a significant portion of Radio Poder’s listeners, according to station director Arturo Sarmiento, but also their volunteer staff. “Some of them are working in the fields and, after their work, come to do their radio shows,” he said.

During the early days of the pandemic, the station garnered national attention for translating information about Covid into Spanish and indigenous languages. That included letting undocumented residents know that they could apply for pandemic relief. At the heart of Radio Poder’s success is partnerships with nonprofits and state agencies to offer information about everything from affordable housing to labor rights. On the first Wednesday of every month, for instance, two staff members of the local nonprofit Farmworker Housing Development Corporation present En Tu Casa (In Your House) FHDC to inform listeners about housing issues. MLP Mujeres de la Comunidad focuses on women’s issues in partnership with Mujeres Luchadoras Progresistas, a grassroots organization of female farmworkers.

But Sarmiento said that it was just as important to include programming for women — including on-the-job issues for female farmworkers — and children. “More than broadcasting for workers, we broadcast for families,” Sarmiento said.

Pearls of Wisdom

“AM radio is probably not the wave of the future,” Biehl-Owens admitted. Even so, the recent loss of internet and cell communication in Western North Carolina following Hurricane Helene served as a reminder that AM radio still plays a crucial role in informing the public.

And it’s clear that farm radio still cultivates a strong bond with its listeners. Whether it’s the RRN’s farmer-owners or the farmworkers learning how to report on the fly for Radio Poder, farm radio is one of radio’s pillars.

One of the things that keeps Ishee going is when his listeners recognize him in public. “They say, ‘Hey, I listened to that report the other day that you did on Alpine dairy goats … You know that was really interesting, and I’m going to learn more.’”