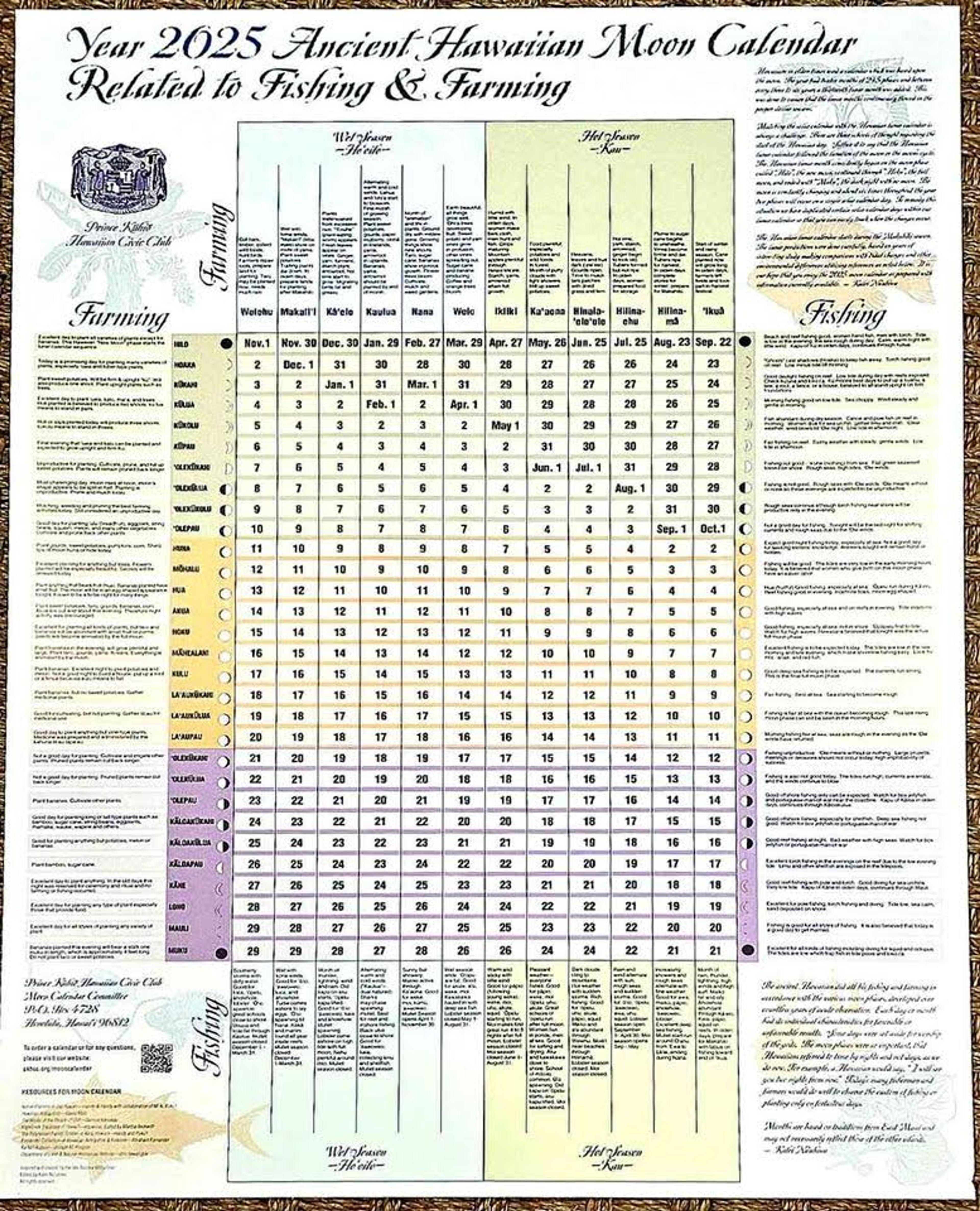

In Hawai‘i, an ancient lunar calendar has guided Native farmers and fishers for centuries.

When Kāwika Lewis is teaching keiki (children) how to plant fruit and vegetables on his family farm north of Hilo, he often uses guidance from the Hawaiian moon calendar. Different lunar phases can signal whether that particular day is fortuitous for planting, cultivating, or pruning. Lewis tells his visitors that, if the crescent moon is facing upwards — like an upright bowl — then it’s fine to plant.

On the other hand, “We do not plant when the bowl is facing upside down, when it’s empty,” Lewis said. “That represents a bowl that cannot hold anything.”

For centuries, Native Hawaiians have let the moon steer their farming and fishing. Today, locals are leading the charge in keeping those traditions alive — and modern agriculture organizations like the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council (WP Council) are embracing the benefits of ancient knowledge, too. These annual moon calendars have long been created to guide outdoorsmen and women in their endeavors, and proponents believe they can be utilized in communities outside Hawai‘i.

Agriculture producers on the islands say the lunar phases dictate the tides, fish spawning patterns, plant water content, and the amount of light available on a given day. That helps them determine what sea creatures to catch and which plants to cultivate. Some techniques have been analyzed by Western scientists, while others remain understudied. Regardless, many Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) put faith in these ancestral practices and are working to revitalize them today.

The moon’s gravitational pull on the tides and its effect on fishing are much discussed among sportsmen and women, with researcher Nur Aida Athirah Sulaiman concluding that lunar phases and tides impact sea life’s behavior. “The moon phenomenon indirectly affects the biological cycle of living species including fish,” she wrote in the International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences.

On the other hand, the University of Illinois Extension’s College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences depicted the science behind the moon’s influence on plants as “difficult to find,” though it conceded that further studies need to take place on the topic. The school cited recent findings that lunar gravity “is so negligible it cannot have significant influence over plant processes,” but researchers also found unexpected ties, such as the moon’s potential impact on plants’ pollen production.

According to the Hawaiian lunar calendar, Hilo, or the new moon, signals good fishing, with low evening tides, according to The Kohala Center. It’s also an excellent day for cultivating every crop except mai‘a (banana). However, the four phases of the waxing moon won’t suffice for planting or fishing, with rough waters and high tides. During Muku, or the dark moon, banana stalks grow, and fishing — especially diving — is recommended.

Lewis has focused on circulating that knowledge since 2016 when he founded ʻĀina University, a nonprofit that promotes reconnecting with the ʻāina (land). Lewis has hosted more than 50,000 visitors at his farm and takes that opportunity to introduce them to the kaulana mahina (moon calendar). “It’s inside of my DNA,” said Lewis, referring to his Kanaka Maoli ancestry.

The moon phases are being shared at both the institutional and local levels. Honolulu-based television station KHON2 News broadcasts the Hawaiian lunar phases to viewers, and the WP Council produces free lunar fishing calendars for not only Hawai‘i, but also American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands.

“Each region has their own older fishing traditions and kind of gear and what kind of fish are there and how they catch them,” said education and outreach coordinator Amy Vandehey at the WP Council.

The WP Council is a congressionally-created regional fishery management council that’s involved in fisheries across those islands, with a focus on incorporating Indigenous perspectives from local communities. Before the council started distributing the lunar calendars, many fishermen followed the moon phases on their own, Vandehey said.

“Typically, people end up learning it from other people, whether it be from family or friends,” she added.

Now, the council produces between 1,000 to 2,000 large classroom versions and 500 to 1,500 small waterproof versions for boat use — “and they definitely go quickly,” Vandehey said.

Haunani Miyasato also designs an annual moon calendar in ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) and leads mahina (moon) workshops that teach schools, organizations, and community members about the moon from a Hawaiian perspective. Local gardeners, farmers, fishermen, surfers, paddlers, and medicine makers often attend. The former teacher decided to make her own calendar to help her four children learn the lunar phases, which fall on different Gregorian dates each year.

“Some moons, you plant things, and some moons, you harvest or prune.”

“Growing up, we always heard some moons are better for fishing and, some moons, you don’t go fishing on at all,” Miyasato said. “Some moons, you plant things, and some moons, you harvest or prune.”

She also teaches the reasoning behind why certain lunar phases are better suited for their respective activities. For example, if someone wants to gather ʻopihi, a shellfish found on the shoreline, then low tide would be ideal for the best access, and daytime would allow for the most light to do so. Therefore, a moon phase that correlates with low tide during the daytime makes the most sense.

The ʻŌiwi (Native) belief is that the theory can also be applied to plants, Miyasato explained, because nutrients are supposed to travel through the plant during different lunar cycles.

“The waters of the ocean are pulled by the moon,” she said. “The waters in our plants are also pulled by the moon, too, so it’s like there’s a tide in our plants.”

Other Indigenous cultures use similar systems of planting, Miyasato said. She likens the kaulana mahina to North America’s Old Farmer’s Almanac. First published in 1792, the almanac explains the significance of full moons and includes a moon phase calendar.

“It gives you some excuse as to what to blame it on if you don’t catch, too.”

Gil Kuali‘i is a Hilo lawai‘a (fisherman) and the Hawai‘i advisory panel vice chair at the WP Council. Kuali‘i says he and other Kānaka Maoli watermen plan their fishing expeditions based on the lunar phases because of their impact on the tides. The kaulana mahina can also correlate the spawning cycles of different species, Kuali‘i added.

The extra information promotes business productivity among fishermen, Kuali‘i said. “We’re really just scratching the surface on what this calendar can provide.”

Other Hawai‘i residents who aren’t of ʻŌiwi ancestry also use the lunar phases as a reference point.

Jeff Fay has owned Kona’s Humdinger Sportfishing, a family-run charter fishing business, since 1975. Originally from California, he now predominantly caters to tourists in Hawai‘i. Before they set off on his boat, Fay checks the lunar app on his phone, on top of other factors like the currents and the weather.

His business advises clients to fish on the full moon and the new moon — the best time to catch ‘ahi (tuna). The days near the full moon are also well-suited for blue marlin fishing. Fay explained that lunar phases affect when the fish feed and bite, and tidal changes mean increased activity.

On top of that, “It gives you some excuse as to what to blame it on if you don’t catch, too,” he joked.

Author’s note: Megan Ulu-Lani Boyanton identifies as Kanaka Maoli.