As the sport of gravel cycling explodes across rural America, some communities are experiencing growing pains.

Mistakes were made. To that, everyone can agree.

In 2019, Steamboat Springs, Colorado, became host to the region’s first ever Steamboat Gravel (SBT GRVL), a gravel cycling race that involved 2,000 participants hitting the rural, dirt, and gravel roadways of Routt County in distances that can top 100 miles. While the cyclists enjoyed the event, local ranchers experienced what they say was a long list of difficulties.

It was the county fair weekend, for starters, and many ranchers struggled to get out of their driveways to participate in events. It was also haying season, when ranchers can’t afford to lose time on the surrounding county roads. There were complaints about strewn trash, cyclists using ranchland as bathrooms, and overall rude behavior from the participants. And then there were the spooked cattle, startled by large packs of cyclists whizzing by at high speeds. “Ours got to running, hit the fence and broke through,” said Trenia Sanford, owner of the v\Ranch-Semotan Ranch. “It took us more than two-and-a-half hours to get them back. Once they learned how to escape, they kept doing it.”

Mistakes were made. But in the ensuing years, the two disparate communities of cycling and ranching have worked together to hopefully find a peaceful co-existence. This year’s late June event will serve as a proving ground.

Working Toward a Solution

Gravel cycling — something of a hybrid between traditional road biking and mountain biking — is the second-fastest growing category of the sport, behind e-bikes. Cyclists are drawn to the opportunity to ride at high speed on quiet, bucolic roadways, far away from busy traffic full of distracted drivers. And, as the sport explodes, so too have events around the country. Colorado, with its beautiful vistas and plentiful dirt/gravel roadways, is a natural spot for race organizers to target. Cyclists have shown their willingness to travel from all areas of the country for a chance to ride there. They bring with them plenty of tourism dollars for local hotels, restaurants, and more, which surely does hold appeal, especially in town proper.

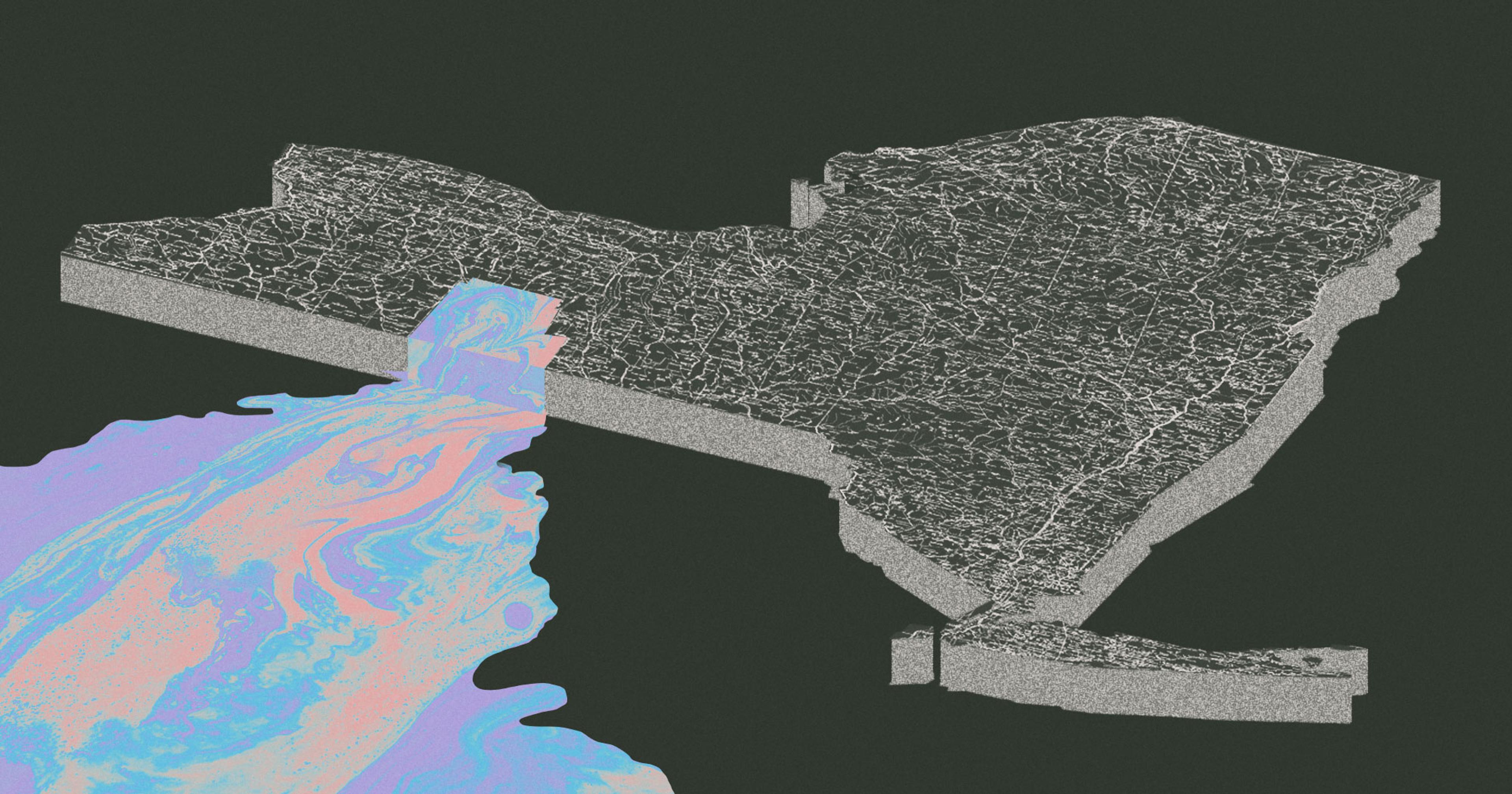

But there are limits, say the ranchers, and questions of who exactly benefits from the influx of dollars — not to mention the need to avoid overtourism and protect the agricultural heritage of Routt County. “There’s a reason everyone wants to experience the area,” said Nancy Mucklow, who along with husband CJ has leased land for their alfalfa, hay, grass, and cattle farming for decades. “It’s pristine and uncrowded. But we have a master plan that prioritizes agriculture over tourism, so we’re not set up for large crowds of people.”

Following the first year of SBT GRVL, the ranchers compared notes and took their case to the county commissioners. Amy Charity, founding partner and CEO of SBT GRVL, was all ears, and created a second listening session a few months later. “The primary issues were the fact that the date of the race coincided with the Routt County Fair, there was two-way cycling traffic on the roads, which caused delays, and that not all rural residents knew the dates and timing of the event,” she said.

“We have a master plan that prioritizes agriculture over tourism, so we’re not set up for large crowds of people.”

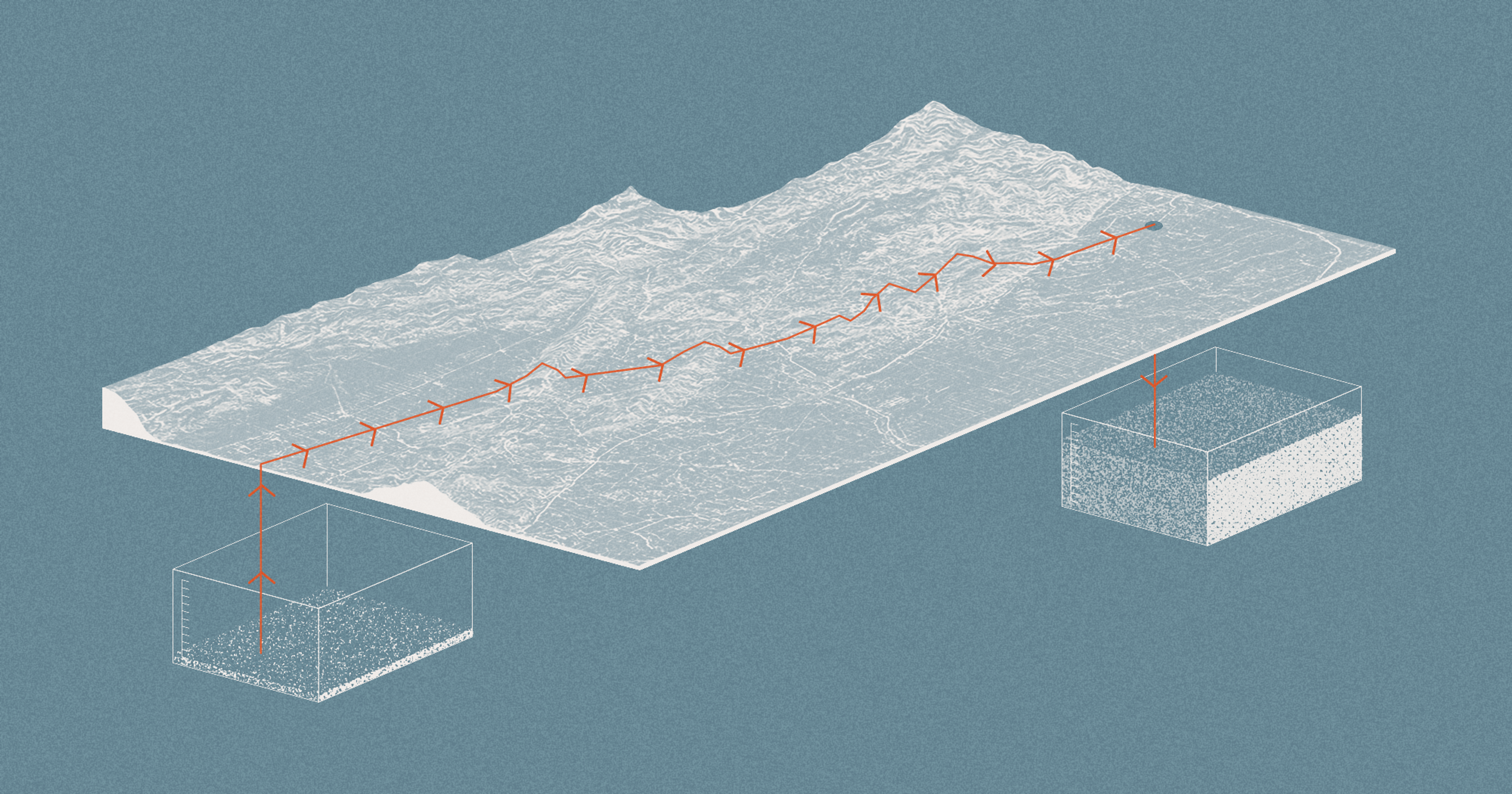

Each year, Charity and her organization have worked to improve the situation, even as it expanded over the past few years. In 2024, the key changes included moving courses to a more remote location in the county; eliminating two-way cycling traffic; altering the timing and course routes to avoid commuting delays; increasing sheriff and police presence, medical support and traffic control; adding a command center; attempting to visit every on-course residence to communicate event day impacts; increasing on-course signage; and educating participants on the local rules of the road and stewardship.

Going into this year’s SBT GRVL all those changes will continue, in addition to others. “We’re moving the date away from haying season and the county fair,” said Charity. The organizers have also split the event into two different days, the first featuring a leisurely “ride” and not a race, and the second serving as a circuit race that begins and ends in Hayden, a small town about 20 miles outside of Steamboat. The total number of cyclists will top out at 2,500, down from last year’s 3,000.

Amber Pougiales, executive director of the local Community Agricultural Alliance, says that the ranching community is optimistic. “The race director has done a lot to mitigate the various issues, and moving the date will be huge for the ag community,” she said.

For her part, Pougiales sees great need for cohesion. “The sport wouldn’t exist without the rural communities, and I think the ag community can gain from the relationship, too,” she explained. “An event like this is an opportunity to create respect and appreciation for the rural landscape and the work that goes on there.”

A Roadmap

Ranchers are no strangers to conflict, whether with the federal government, housing developers, or even allowing land access to hunters. In most cases, they’ve had to work with the other party to achieve a peaceful solution.

As SBT GRVL and Routt County work out the kinks, they may take a page from Gunnison County, its distant neighbor to the south. Home to the towns of Crested Butte and Gunnison, each with long histories of mountain biking and, lately, gravel cycling, there’s an established blueprint for ranching/cycling cohesion. “We’ve worked hard with the ranching community to develop good lines of communication,” said Tim Kugler, executive director of Gunnison Trails, a non-profit trail advocacy organization. “When we started Gunnison Trails, we were forward thinking and quick to offer help and let the ranchers know we didn’t want to mess with their operations.”

To that end, Gunnison Trails has educated cyclists about keeping gates closed when they encounter them, added cattle guards in appropriate places, and has chosen not to introduce new mountain bike races out of respect for rancher concern (the county will continue hosting its gravel race).

“The overall sentiment I hear is that we are on the brink of over loving the valley, and we should be mindful of the consequences of hosting large events.”

With the emergence of gravel cycling, the organization has ensured that cyclists wait until the local roads are dry and ridable in the spring before they take to their two-wheeled steeds. The town’s Gunni Grinder gravel race is now entering its fourth year, features three race distances up to 120 miles, and remains smaller than its Steamboat counterpart. “The gravel scene is young here, and as it stands, we don’t have any issues,” said Kugler. “We are sensitive to anything that can grow quickly and keep good communications open.”

Rancher Hannah Cranor-Kersting, director of Gunnison County’s extension office, pointed out that organized recreation like gravel races is relatively new when compared to agriculture. “Obviously there can be conflict, and issues will pop up,” she said. “But we’ve been able to work together so that both sides can be happy with the outcomes.”

Ultimately, each community is unique and will respond to its issues differently, whether from the ranching side or the cycling side. The 2025 race weekend in Steamboat Springs took place in late June, and Mucklow hasn’t heard much negative feedback. Steamboat Gravel’s 2026 permit request will go in front of the county commissioners for approval in late July, which will make or break its future.

Mucklow had this to say: “The overall sentiment I hear is that we are on the brink of over-loving the valley, and we should be mindful of the consequences of hosting large events in a valley that isn’t set up for hosting large numbers.”