Cheese made from raw milk is safer — and more legal — than consuming it straight. Its proponents are thrilled about the robust flavor variations.

On a foggy March day in Putney, Vermont, about 40 cheese professionals, wearing mostly plaid shirts and wool sweaters, gathered at a conference inside a renovated whitewashed barn framed with dark wooden beams. There was a homey smell of manure in the air, and soft light filtered in through the big windows. At the front of the room, a microbiologist was giving a 1.5-hour lecture about mold. Instead of yawning or looking out the window, most members of the audience were literally on the edge of their seats. Many knew each other already, but this was their first time meeting for an inaugural conference on the science and craft of raw milk cheese; the excitement in the air was palpable.

Public health agencies in the U.S. have warned Americans about the dangers of raw milk consumption since the 1920s, when pasteurization became widespread. Recently, concerns about the safety of milk have resurfaced in a big way with the spread of avian flu to dairy cows, cuts at the FDA, and a concurrent fascination with raw milk across broad swaths of popular culture. But what to do with raw milk cheese, the aged cousin of the controversial white liquid? The answer historically has been less clear.

The CDC recommends that pregnant women avoid raw milk cheeses, even those aged for over 60 days, such as Gouda, cheddar, or the king of raw-milk cheeses, Parmeggiano-Reggiano. Meanwhile, the FDA has repeatedly placed restrictions on raw milk cheeses imported from Europe, including effectively banning well-known favorites like Roquefort.

The U.S. is more cautious than most other countries. Less than a day’s drive north of Vermont, in the Canadian city of Montreal, customers at cheese shops like Bleu & Persillé can buy tiny rounds of wrinkly raw-milk cheeses imported from France that are only a few weeks old. But south of the border, since 1949, the importation or sale of young raw milk cheeses like Crottin, Brie, or Camembert has been illegal.

For government regulators, the higher counts of microbes in raw milk cheeses are cause for concern. But for participants at the conference in Vermont, raw milk cheeses like Parmesan have a proven safety record, and those microbes — and their unpredictability and mystery — are something to celebrate.

“We actually have no idea what molds are out there in the landscape,” said Benjamin Wolfe, associate professor of biology at Tufts University. Behind him, colorful graphs illustrated microbiomes he’d discovered on cheeses around the Northeast. “Molds are like the beavers of cheese,” he explained, “little fuzzy creatures” whose actions shape the landscape of the cheese rind. All cheesemakers know how important mold is for the final taste of their cheese. But Wolfe explained that we have no idea how much diversity is out there, diversity that can be lost with pasteurization. At his lab, “we’re trapping molds, we’re hunting molds,” and Wolfe’s graduate students are combing through the New England landscape for unidentified microbes. “Literally in my backyard we found a new species of penicillium we’re working on describing.”

Peter Dixon, Parish Hill Creamery (L) and Brian Civitello, Mystic Cheese, CT (R)

·Photo by Lacey McNeff

This wilderness of mold microbiota, about which we know surprisingly little, is especially exciting to raw milk cheesemakers who — to put it bluntly — think pasteurized cheese is boring.

In fact, the co-hosts of the conference, Rachel Fritz Schaal and Peter Dixon at Parish Hill Creamery, not only want more raw milk cheese on American plates, but want cheesemakers to make it from scratch, using their own starter cultures. This method of using autochthonous (indigenous) cheese cultures is practiced widely around the world, from Italy (think Parmesan) to Colombia — but not in the U.S.

In fact, although in 2025 most consumers have heard of sourdough bread, natural wine, or wild-fermented beer, there are still fewer than ten producers of “wild” cheese in the U.S., according to Fritz Schaal. In a similar way to sourdough bread, cheese can be made by letting fresh raw milk sour into a sort of natural yogurt, and using that yogurt to inoculate a vat of milk, instead of freeze-dried imported microbes which are standard in the industry.

Dixon, Fritz Schaal, and Wolfe all argue that studying the microbiome of raw milk reveals an important element — terroir, or the influence of place on the final taste. “I have been known to argue at great length that pasteurized cheeses do not have terroir,” said Fritz Schaal. The reason is that pasteurization “flattens” the milk, turning it into a blank slate.

In addition to killing potentially harmful microbes, pasteurization gets rid of any local microorganisms that may have originated in the locale where the animals grazed. Most cheesemakers then add industrially produced powdered cultures to produce the flavor notes that they want in the cheese. These freeze-dried cultures come from as far away as Denmark, and the result, according to raw milk aficionados, is that a lot of pasteurized cheese basically tastes the same. According to Dixon, the goal with raw milk cheesemaking is to “drag the pasture into the cheese,” anchoring it to the creamery where it’s made.

Cheese acquires a natural rind while aging in the cellar at Parish Hill Creamery.

·Photo by Rachel Fritz Schaal

Terroir for cheese takes a more circuitous path than with wine: soil to grass, grass to milk, and then milk to cheese. In studies performed by Wolfe’s lab at Tufts and the D’Amico Microbiology Lab at the University of Connecticut, fungal genetics has revealed that the microbes present in the air, on the wall, and on cheesemakers’ hands on the day the cheese was made showed up in the final product months later. Wild mold strains from the leaves and grass outside, and of course those from the animal producing the milk, also influence the cheese’s development. Even sea salt can introduce microbes captured from the ocean. The result — if done right — is a cheese that cannot be replicated anywhere else.

On the last day of the conference, participants tried three cheeses made as part of the Cornerstone Project, in which multiple cheesemakers in different states commit to make cheese according to the exact same recipe, but each using their own raw milk. Represented on the plate were Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Vermont. The three cheeses were nothing alike. One was yellower than the other two. Another had stronger flavor, while a third tasted creamier. The recipe was the same, but each cheese reflected the evolution of local microbes over time.

Fritz Schaal argues that this kind of unique, regional, raw milk cheese could be the way to keep more small producers in business. “It is not enough to make cheese at a small scale. You have to make something exceptional, something that wows. Autochthonous starters are something only you can do.” She is careful to point out that only high-quality, tested, safe raw milk from a trusted source (in her case, a neighboring dairy) will produce the type of cheese she’s advocating for.

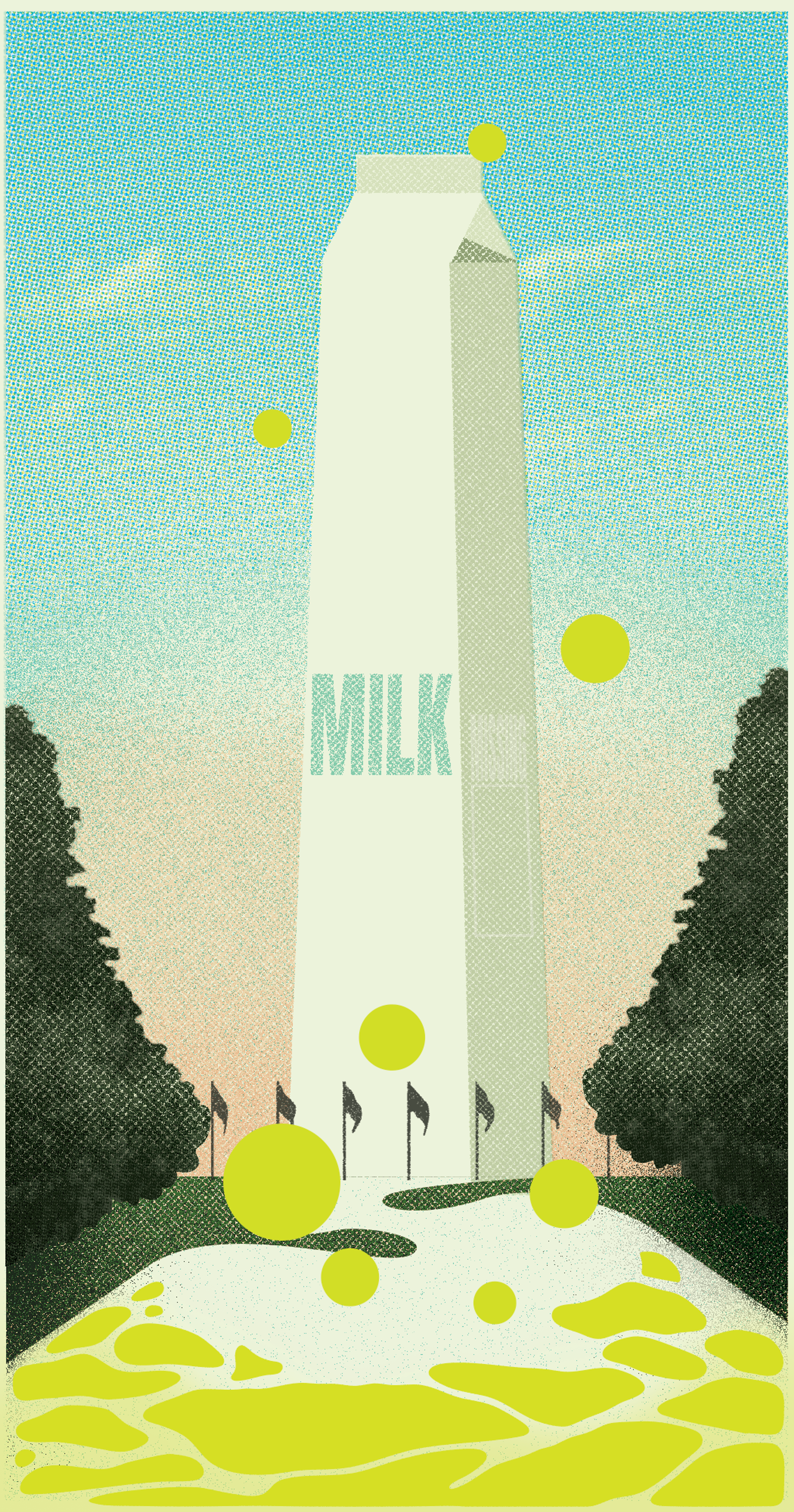

Not all raw milk, then, is created equal, certainly not when it comes to cheese. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., may not have convinced everyone that drinking raw milk is patriotic or American. But raw milk cheesemakers are sure that nothing could be more American than a raw, natural-rinded wheel of cheese, with a microbiotic signature that reads “Made in the U.S.A.”