Consumers are thirsty for raw milk, and more states are looking to legalize its place on grocery store shelves. But is it safe?

Over the last several years, the dairy industry has faced a multitude of challenges — shifts in supply and demand, price fluctuations, consolidations, labor shortages, and more. The number of dairies across the country continues to fall, declining by more than 55% from 70,375 in 2003 to 31,657 in 2020.

Could allowing more sales of raw milk, priced anywhere between $7 and $18 a gallon, be part of the solution? In December, delegates for the Wisconsin Farm Bureau — an organization that represents farmers in the country’s second-biggest milk producing state — flipped their stance on raw milk sales, which have long been prohibited in America’s Dairyland. The bureau even supports “giving farmers more access to consumers through the sale of raw milk” — a major shift for the organization.

What you’ve got is a complete, chaotic, hodgepodge mess of 50 different states of disorder.

Currently, raw milk can only be purchased legally at retailers in 12 states, including California, Idaho, Nevada, Arizona, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina. Despite its legalization in these states, public health experts maintain the consumption of raw milk, which hasn’t been pasteurized, isn’t safe. That’s the stance currently taken by the CDC, which names raw milk as “one of the riskiest foods,” linked to preventable foodborne illnesses and outbreaks every year. And that’s why, in 1987, the FDA mandated the pasteurization of all milk and milk products for human consumption, effectively banning the shipment of raw milk across state lines.

Meanwhile, states like Wyoming and Mississippi have introduced bills that would overturn bans or allow the expansion of raw milk sales. “What you’ve got is a complete, chaotic, hodgepodge mess of 50 different states of disorder,” said Mark McAfee, an organic raw milk producer in California who founded the Raw Milk Institute in 2011. “Things are changing quickly … Consumers want [raw milk] badly.”

And consumers are willing to travel to get it. “There are people in New Jersey that go to Pennsylvania because they believe raw milk has benefits. So while it’s not easy to get raw milk in New Jersey, it’s certainly not impossible, either,” said Rutgers University food scientist Don Schaffner, highlighting the slippery nature and lack of enforcement on such bans.

The debate over raw milk (sometimes called “fresh milk”) is nothing new — and it never fails to elicit a strong discussion. Most of the milk you find in grocery stores today has been pasteurized, which involves heating liquids such as beer, juice, eggs, and, of course, milk, to a high enough temperature for a long enough time to kill harmful pathogens such as salmonella, E. coli, and listeria.

“The pasteurization of milk was one of the great public health boons of the last century,” said Schaffner. It helped eradicate public consumption of bacteria that caused tuberculosis, diphtheria, typhoid fever, and other foodborne illnesses. “Proponents [of pasteurization] believe it would be a giant step backwards to allow people to sell raw milk.”

Raw milk advocates, however, say it’s time to rethink the relevance of century-old standards. Proponents like McAfee say that raw milk is not only tastier, but also easier to digest and more nutritious than pasteurized milk because it still contains beneficial enzymes and bacteria that get killed off during the pasteurization process. “When properly produced, raw milk has a 20-day shelf-life and is absolutely delicious, like melted ice cream,” said McAfee, who also argued that raw milk is “one of the most anti-inflammatory foods on Earth.”

One of the dairymen behind the shift in Wisconsin, Travis Klinker, emphasized that “we’re not farming in the 1920s and ’30s anymore,” during the Farm Bureau’s December meeting. While no raw milk bills have yet been introduced to the Wisconsin Legislature, Klinker proposed implementing standards from the Raw Milk Institute as a way to assure consumers will get a clean, quality product. “We don’t just want anyone cracking a valve on their bulk tank and putting milk in a dirty jar,” he said.

McAfee, who helped write those standards, expects the raw milk market “to continue to grow explosively.” He’s currently working with a Richmond, California-based lab to develop an on-farm pathogen-testing system that would allow raw milk producers to test and track their own milk samples during a shortened time period. “That will be the replacement for the kill-step of pasteurization, in my opinion,” said McAfee. “Pasteurization was an 18th-century solution to an 18th-century problem. We can — and will — do a whole lot better.”

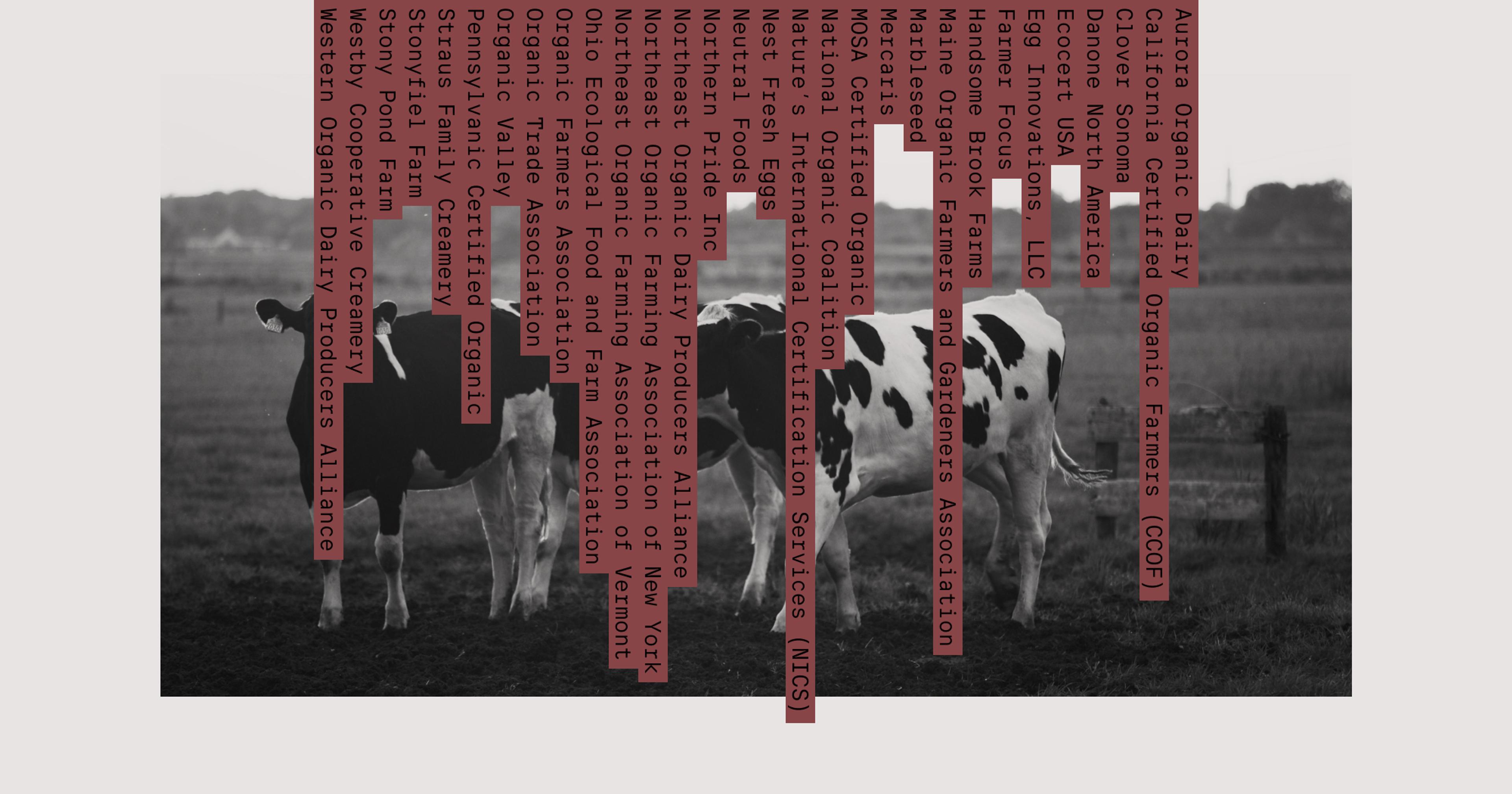

Despite a steady rise in interest among consumers, the raw milk movement still has hurdles to overcome — including hesitation among existing dairy farmers. When Danone, the company that owns Horizon Dairy, terminated contracts with 89 organic dairy farms in New England and eastern New York in August 2021, McAfee reached out to the affected farmers in an effort to entice them to switch over their production. “Those 89 dairies could have shifted to raw milk production, but they didn’t,” said McAfee. “One did, is thriving, and is doing great … but the others were not really willing or interested in shifting.”

The public mindset around raw milk is disjointed, too. “If you poll food scientists and food microbiologists like me around the country, I think you would find that almost overwhelmingly, people like me are opposed to raw milk,” said Schaffner. “If you want to drink raw milk, that’s your business … If you want to go sky-diving, go for it. But don’t fall on my house.”