As broadband access slips away from rural farming communities, new research shows particular harms to the young.

Some farmers keep livestock in their barns. Others store off-season equipment. But in Neil Mylet’s rural Indiana barn, you’ll find 10 miles of fiber-optic cable. Mylet, a corn and soybean farmer and tech entrepreneur, has long understood the importance of internet connectivity for rural ag communities — and the frustration with its absence.

Fourteen years ago, then-25-year-old Mylet was eager to show off the prototype of a new invention that would allow farmworkers to monitor and control the loading of grain trucks using an iPad or smartphone. Working with friends, he filmed a promo video to share with the world.

“We shot it in like two hours, and almost wrecked a semi in the process,” Mylet recalled. “I was literally using our forklift as a boom truck for a camera.”

But the technical challenges of shooting the video weren’t the primary roadblock: Mylet didn’t have enough bandwidth to put the video online. “I had to drive practically an hour to upload it to YouTube,” he said. On top of that, lack of fast internet access made his grain monitoring tool less useful. The delay between the video stream and when it showed up on a user’s screen was a problem. “It would pause here and there, and the flow rate that we have for this process is 25 tons of grain per minute. If you have even a five-second intermittent pause or freeze, that’s a really bad situation.”

Today, that early project continues inspiring Mylet to work toward a better-connected future for rural agricultural communities — and the young people who grow up there. He’s spent the last few years working to convert an old opera house in Camden, Indiana, into a tech hub, coworking space, and venue, where he hopes to foster the growth of students and entrepreneurs like himself through internships and access to high-speed internet.

“We already essentially lost or greatly injured a generation of these rural kids,” said Mylet. “When you don’t have [high-speed internet] and you don’t grow up with it at an early age, it’s striking the differences in the way they see the world, the way they think about opportunity, the way they take on an entrepreneurial view.”

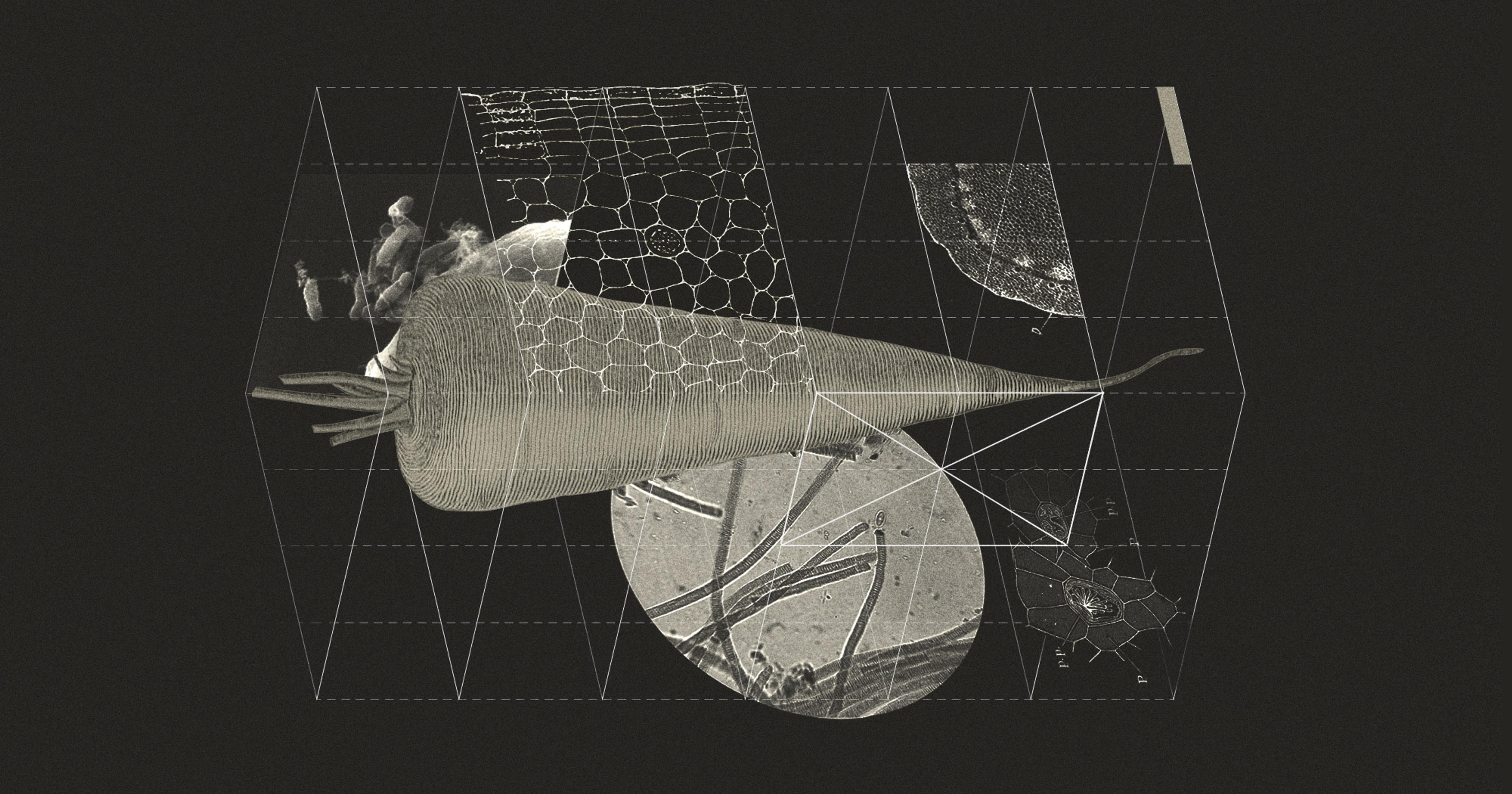

Concern for opportunity was one impetus behind a recent study from Michigan State University examining the impact of poor broadband access on rural students. Before the pandemic, the researchers surveyed middle and high school students in rural Michigan, assessing how broadband access impacted “academic performance, educational aspirations, career choices, and general well-being.” The new study illustrates how the improved connectivity gained by some rural Michigan students during the pandemic is now receding.

“One thing the pandemic did do, for all the evils it wrought on this world, is that here in the United States, we finally, finally realized that high-speed, affordable broadband is not a luxury,” said Christopher Ali, telecommunications professor at Penn State and the author of Farm Fresh Broadband: The Politics of Rural Connectivity.

That realization was a silver lining for many Americans without high-speed access in both rural and urban communities during the pandemic. Among other state and federal efforts to increase connectivity, Congress approved the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) as part of the 2021 Infrastructure Act, providing 23 million low-income households with a stipend for broadband access.

As connectivity declined, so did the students’ interest in completing college or pursuing careers in STEM.

But for all its success, a lack of infrastructure meant the ACP’s financial subsidy alone couldn’t help many rural families. And Congress let the ACP expire at the end of April, leaving those who were taking advantage of the stipend without support.

“That’s definitely going to be affecting the already significant decline [in high-speed internet access] that we found among adolescents, especially in rural areas,” said Gabriel Hales, a research assistant at Michigan State and co-author of the study.

“Even if it was cheaper, even if it was free, a lot of these households in rural areas don’t even have the ability to go up to an internet service provider and get access because there’s no infrastructure, there’s no ability to get any sort of internet,” Hales continued.

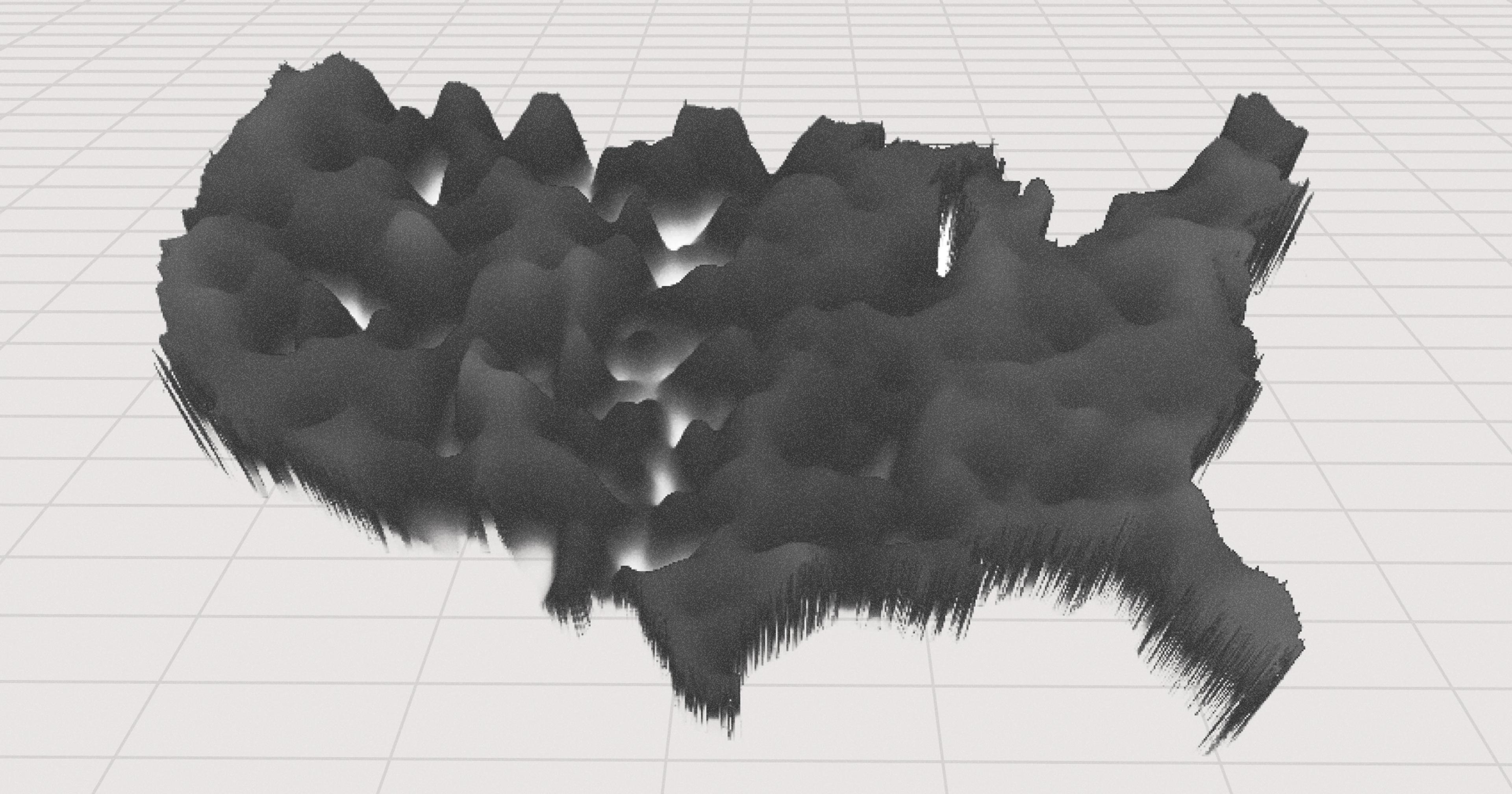

That’s why a crucial part of Hales‘ team’s research entails carefully mapping rural connectivity in Michigan, and identifying which homes have the infrastructure to accommodate high-speed internet. Without this kind of mapping nationwide, Hales said connectivity will remain out of reach for many rural students.

By the end of 2021, rural Michigan student home internet access increased by 16 percentage points, researchers found, thanks largely to schools providing wi-fi hotspots. But by the end of 2022, that access was declining, a downward trend that Hales expects will continue. And as connectivity declined, so did the students’ interest in completing college or pursuing careers in STEM.

“Even if it was free, a lot of these households in rural areas don’t even have the ability to go up to an internet service provider and get access because there’s no infrastructure.”

Lack of high-speed internet access impacts students in both urban and rural settings, but the latter often have fewer options, Ali said. “The difference between being unconnected in an urban community and a rural community is literally distance. Where are you going to get connected? Is there a library within walking distance? Are there other community centers? There’s just more opportunities for connectivity in urban areas.” When access does exist, Ali added, rural, Indigenous, and remote communities often pay much higher prices for subpar broadband.

The benefits students attain through broadband access aren’t just academic. Accessing the internet during the pandemic, even just to play video games or scroll social media, “was incredibly important to make sure that these adolescents kept up that level of well-being and did not feel as isolated,” said Hales. While he acknowledges that research tying teen social media use to poor self-esteem is prevalent, that wasn’t reflected in their findings. And beyond self-esteem and social connection, even just “goofing off for a few hours every day” online helps rural students build vital digital skills, he added.

While the ACP has expired, Ali points out that millions of dollars will be funneled to the states through the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment program (BEAD), also part of the 2021 Infrastructure Act. But that money won’t be distributed to the states for another year. In the meantime, many rural communities are out of luck. “We just have so many gaps, and unfortunately rural communities often pay the price of these gaps,” said Ali.

“How are we going to empower our young people to pursue their dreams?” he continued. “Without access, you can’t apply for a job, get a voter ID card, you could barely book a vaccine. This is the struggle that young folks in rural communities are going through. Let’s make it easier for these kids.”

As the states wait for BEAD funding, Mylet continues to take matters into his own hands. He is now providing high-speed internet for his local library. Caitlyn Baird, director of the Camden-Jackson Library, said the faster internet has been a game changer for young and old library patrons alike.

Baird, who has three kids, said high-speed internet is non-negotiable now that instead of snow days, schools have “e-learning days.” “If we didn’t have the access to run three computers at one time and enough internet to sustain that, I don’t know how we would do their learning,” said Baird. “They’re requiring these kids to be online the whole day … It is very important that they have access.”