The meat industry is railing against “radical vegan activists.” What are they really upset about?

In 2023, 386 protests related to agriculture occurred worldwide, according to a report issued by the Animal Agriculture Alliance, a Virginia-based nonprofit founded in 1987 primarily to monitor anti-meat activity. These protests, undertaken by what the Alliance refers to as radical vegan activists, included banner drops, vandalism, trespass, and animal theft, and were evidence, the authors of the report wrote, of an “extremist agenda” to “eliminate meat, poultry, dairy, seafood, and eggs from Americans’ diets.”

An activist group called Direct Action Everywhere (DxE) elicits especially strong reactions from the Alliance. DxE films alleged animal abuses on industrial-scale farms and conducts open rescues of sick animals; the Alliance refers to DxE as an “extremist group” and suggests that its members may have spread avian influenza between poultry operations during protest actions (which DxE refutes). However, DxE is just one of several organizations — including PETA, the ASPCA, the Good Food Institute, and the Humane Society of the United States — the Alliance accuses of extremism in advocating for better treatment of farmed animals.

By all market metrics the meat industry is thriving. And yet, from some of its corners, “radical activist” accusations are being lobbed not just at animal rights groups but at farmer-led organizations, too. Additionally, evidence recently emerged that the meat industry is working with the FBI to charge activists under federal anti-terrorism Weapons of Mass Destruction legislation. So, what’s the industry’s real beef?

“From our perspective, we don’t view animal rights activists as animal welfare activists, because their agendas do go much further than animal welfare,” said Emily Ellis, communications and content manager for the Alliance, which has official ties to Cargill and Smithfield and meat industry lobby groups like the National Chicken Council and American Farm Bureau Federation. She said videoing farm practices, public pressure, and pushing for animal welfare legislation are all “a danger to food security [with a goal of] trying to raise the cost for farmers and ranchers to stay in business.”

Although the current industry rhetoric around animal activism sounds extreme, there’s nothing new about advocating for animals. Jainism, a 2,500-year-old Indian religion, prohibits the killing of any animal for any reason; Ireland passed the first anti-cruelty law in 1635, banning the pulling of wool off live sheep; modern Western dialog about whether animals have rights dates to the 1960s.

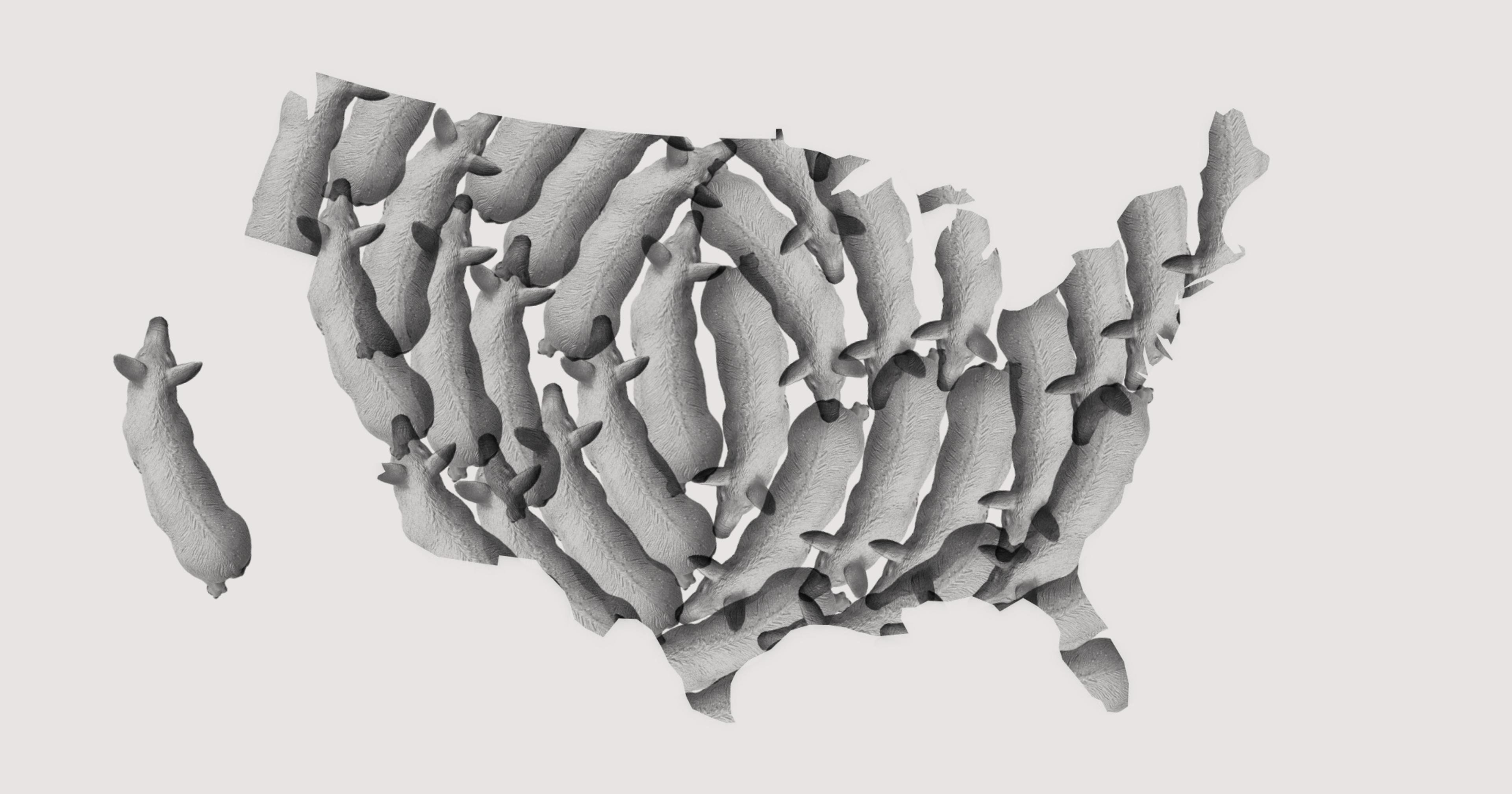

But the meat industry and animal rights groups are clashing at an interesting moment. Some 70 percent of American consumers say they care about how meat animals are treated, even as 10 billion cows, sheep, hogs, chickens and other livestock in the U.S. are being raised on industrial-scale farms, in conditions animal welfare advocates consider inhumane. Just 1 percent of Americans identify as vegan in the face of continued strong meat consumption; annually, per capita, we eat 58.1 pounds of beef, 50.2 pounds of pork, and 116 pounds of poultry, despite growing awareness that these rates are ultimately unsustainable for planetary and human health.

Animal Ag Alliance

“Some animal ag businesses are concerned … that as the public becomes increasingly aware particularly of the climate impacts of eating meat, there is going to be increasing pressure” on them, said Delcianna Winders, director of the Animal Law and Policy Institute at the Vermont Law and Graduate School. “They want to preemptively thwart any sort of incursion into their multi-billion-dollar domination of the food industry.”

This is an industry that’s controlled by a handful of companies — Cargill, Sysco, JBS, Tyson, and Smithfield — and has been scrutinized by Congress for monopolistic behavior. Its $132 billion in revenues is largely reliant on confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) with high stocking densities that observers say have negative impacts on animal welfare. “You can’t provide individualized care to broiler [chickens] when you’ve got 10,000 in the barn,” said Bob Fischer, an animal ethicist at Texas State University. (In fact, large CAFOs can house 30,000 or more broilers.)

CAFOs have remained steadfastly resistant to transparency and some states with many of them, like Iowa, have passed ag-gag laws to discourage and punish whistleblowers, helping maintain an atmosphere of secrecy — although they’ve frequently been overturned on First Amendment grounds. DxE and other activist organizations seek to open them up to wider public scrutiny. Undercover video recordings from CAFOs and slaughterhouses have shown chickens slaughtered without first being stunned, lambs needing their throats cut multiple times to induce death, and mass-killings of pigs by ventilation shutdown, for example. “The more you look into these facilities the more you see they absolutely rely on deceiving [consumers], because we would not be okay with the truth if we saw how these animals” are being treated, said Cassie King, DxE’s communications director.

Activists say such practices violate what few animal rights laws are on the books. “There’s no federal law that applies to animal welfare at the farm so the main laws that protect farmed animals exist at the slaughterhouse,” said Will Lowrey, legal counsel at legal advocacy nonprofit Animal Partisan. The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act (which does not apply to poultry) prohibits things like dragging conscious disabled animals across the floor and mandates stunning before “they’re shackled, hoisted, and cut, although it’s got some other requirements about how to move them when they’re being loaded or unloaded,” Lowrey said.

“From our perspective, we don’t view animal rights activists as animal welfare activists, because their agendas do go much further than animal welfare.”

There’s also the 28-Hour Law that requires in-transit (non-poultry) animals be offloaded for food, water, and rest; and state animal cruelty laws that Lowrey says are largely futile, since prosecutors fail to act on them. “There’s a litany of excuses like, this is a USDA issue, I don’t trust the evidence … or I don’t have the resources,” he said, “so at the end of the day you have billions of farmed animals that effectively have no legal protection whatsoever.”

The Alliance’s Ellis said protest actions to “dictate animal welfare practices oftentimes are more based on emotion rather than actually what animal welfare experts would recommend.” Although she declined to offer examples of what the Alliance considers good or bad animal welfare practices, its website links to species-specific recommendations like the Beef Quality Assurance and the National Chicken Council’s animal welfare guidelines. Some of these stress “positive welfare outcomes” and “humane death,” but Winders said they still allow for practices such as cows being chained at the neck, calf isolation, and lack of outdoor access.

“I have spoken to a lot of people who think that factory farming is not something that they ever buy from,” said King. “They don’t realize that 99 percent of products at the store … are coming from concentrated animal feeding operations.” Fischer agrees there’s a disconnect — although he also believes many consumers would prefer to remain ignorant of livestock practices. Still, he said, “The question isn’t really whether we’ve got responsibilities to care for these animals. The question is, what are we, collectively as a society, willing to spend on that?”

Change, he said, necessitates a government that’s willing to subsidize welfare standards that make it so that “farmers can produce in the ways that make both them and consumers feel good about what they’re doing.” That’s the aim of the Industrial Agriculture Conversion Act, introduced in the House by Reps. Alma A. Adams (D-NC) and Jim McGovern (D-MA) and in the Senate by Cory Booker (D-NJ), which would offer “climate-smart” grants to CAFO producers to switch to “more sustainable and humane” practices. “And you have to have consumers be willing to moderate their consumption so there isn’t as much pressure to drive prices all the way to the bottom,” Fischer said.

The industry is strongly pushing back against other legislative changes. Proposition 12, which passed in 2018 in California with 63 percent of the vote, decrees that crates for veal calves, egg-laying hens, and pregnant sows allow for some minimal movement; it was challenged before the Supreme Court by the National Pork Producers Council, an Alliance partner. (Ellis said gestation crates are “preferred a lot of times by the animal.” NPPC and other Alliance partners California Milk Advisory Board, Dairy Foundation, Iowa Pork Producers Association, and veterinary pharmaceutical company Zoetis, declined to comment for this story.)

An official with the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA), which has supported Alliance programs, railed against “activists” at a White House farmers and ranchers gathering in October. His invective turned out to be directed at Joe Maxwell, a hog farmer and co-founder of anti-monopoly nonprofit Farm Action, which lobbied to strengthen “Product of U.S.A.” meat labeling. In an email, an NCBA spokesman called Farm Action a “phony farm group” that undermines “producer-led marketing programs that [help] farmers and ranchers be more profitable.” Maxwell counters that NCBA is trying to discredit him because he’s against the status quo of industry control that allows the biggest meat packers to set prices paid to farmers and to “price gouge the consumer,” he said.

Farm Action also applauded Prop 12, which Maxwell said protects from “practices that go against every value that I was raised with on how you treat animals. No farm should deny the transparency that the consumer deserves.” He claimed to be unfamiliar with DxE but said if they’re “taking action where animals are being abused to prove that abuse then yes, I’m for that,” as long as they’re not “trying to sensationalize and promote that which isn’t the truth.”

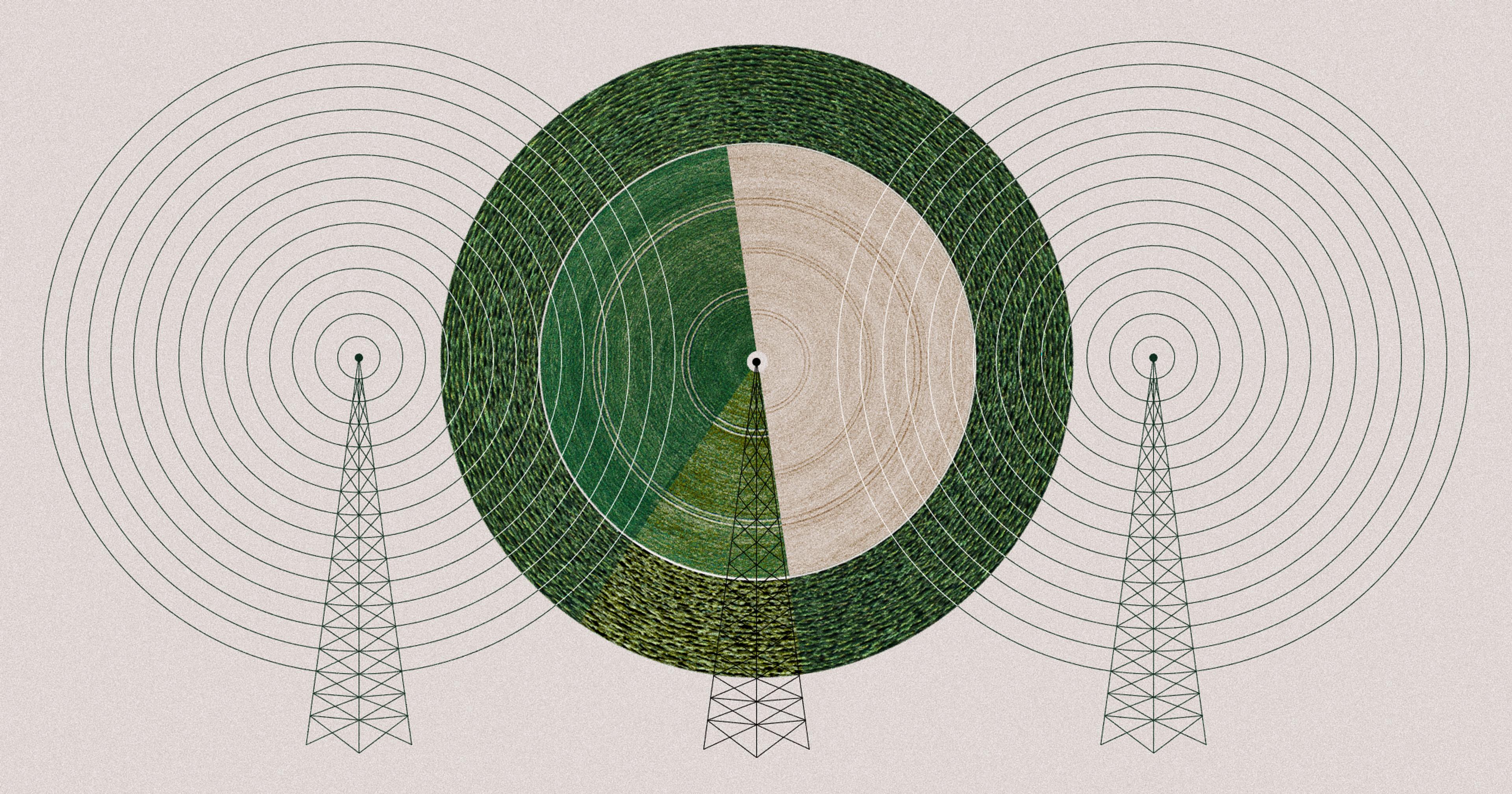

In its battle against DxE and other activists, the meat industry has found a powerful partner in the FBI, which seems to have amped up its decades-long monitoring of animal rights groups. “In the past it may have been, let’s get in, let’s infiltrate, let’s get information, let’s … collect things and surveil,” Lowrey said. “Now it feels more aggressive: Let’s punish these people very heavily.”

He added in a later email, “Whenever you’re talking about using criminal laws that carry a penalty of life in prison, you’ve reached the higher limits of law enforcement’s desire to punish and suppress activism.” Documents released to Lowrey via FOIA requests this past year confirm that the FBI gave a presentation on agroterrorism in the meat industry — a term that more broadly encompasses cyberattacks and the deliberate release of pathogens — at a North American Meat Institute conference in 2020, and solicited collaboration in its attempts to levy Weapons of Mass Destruction statutes against DxE.

Ironically, these sorts of clashes might have been unnecessary if large farms were willing to shed even a small light on what goes on behind the CAFO doors. Ellis said the Alliance supports transparency and encourages farmers to take to social media as a “great way to communicate with people.” True transparency might require a bit more than that. Allowing people to access facilities to see what’s going on “would take away all the force that Direct Action Everywhere has,” said Fischer.