There are many similarities — and marked differences — between Chinese “farmfluencers” and their counterparts in the U.S.

A young woman wears head-to-toe denim, smiling demurely against a backdrop of pumpkin-topped hay bales. A yellow cowboy hat tops her perfectly coiffed hair, and an expensive-looking watch encircles her tiny wrist. It’s just one of a trend of photos proliferating on Xiaohongshu — China’s equivalent of Instagram — featuring Chinese influencers cosplaying as American farmers. They’re aspirational snaps of the glamorized countryside reverie known as American Farm Style.

Although American Farm Style leans purely aesthetic, there’s also a distinct trend of actual Chinese farmers blowing up on social media. Starting around 2020, the popularity of Chinese cottagecore influencers skyrocketed, highlighting luxurious HD pans of elaborate, made-from-scratch meals with ingredients harvested from bespoke Chinese farms. This trend emphasizes the family unit over the individual and highlights traditional tasks such as preserving meat, crafting bamboo furniture, and preparing elaborate feasts for holidays and festivals. Take, for instance, a recent video posted by cottagecore heavyweight Dianxi Xiaoge, titled The Irresistible Yunnan Mushrooms. For her 11.2 million YouTube followers, it’s a languid showcase of multiple preparations of local mushrooms, showing the entire process from foraging to cooking to serving family dinner.

It’s easy to draw parallels between Chinese “farmfluencers” and their American counterparts, and surely there is some crossover. As in the U.S., the challenges of modern urban life have led countless millions to yearn for something simpler, more picturesque. It’s unsurprising that these trends spiked during the pandemic in both countries. Yet in China, where online expression is more carefully monitored and regulated, these seemingly organic trends are connected with a government push for more young people to pursue careers in agriculture and revitalize rural economies.

As in the U.S., Chinese farmland has decreased rapidly in recent decades; according to Foreign Policy, China lost the equivalent of South Carolina between 2009 and 2019. Simultaneously, the Chinese government has been raising the alarm on how much reliance the country has on imported food for its 1.4 billion residents. Since 2004, the CCP’s annual “No. 1 central document,” which highlights the country’s policy priorities, has focused on agriculture, the countryside, and farmers.

“With their homespun videos featuring folksy charm, these influencers are increasingly seen by Beijing as convincing conduits for party-approved messaging,” according to analysis in Japan’s largest financial publication, The Nikkei. “For the mostly young and female ethnic-minority influencers, such an active presence on a Western social media platform is highly unusual, and ordinarily would be fraught with danger in China.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — the alignment with official party goals, China’s farm influencers are finding widespread traction, dovetailing with an overall disaffection with city life and 21% youth unemployment. Cottagecore star Ziqi is a living example, after trading the countryside for city life and struggling to survive. Upon returning to her family’s village home in Northwestern Pingwu, she went viral documenting daily farm tasks. Since then, the hashtag “new farmer project” on Xiaohongshu exploded into 300 million views, and the Chinese government claims that about 20 million have joined the “new farmer movement.”

Another datapoint is Become a Farmer, one of China’s most popular reality T.V. shows. The program pits ten urban youths against the rigors of agricultural life on a 450-acre farm. Beyond building a massive audience, the program helped revitalize the show’s filming location in Zhejiang province, and the participants launched a profitable produce company that now boasts more than 1.8 million followers on Douyin. The second season just aired, and an all-female spin-off is in the works.

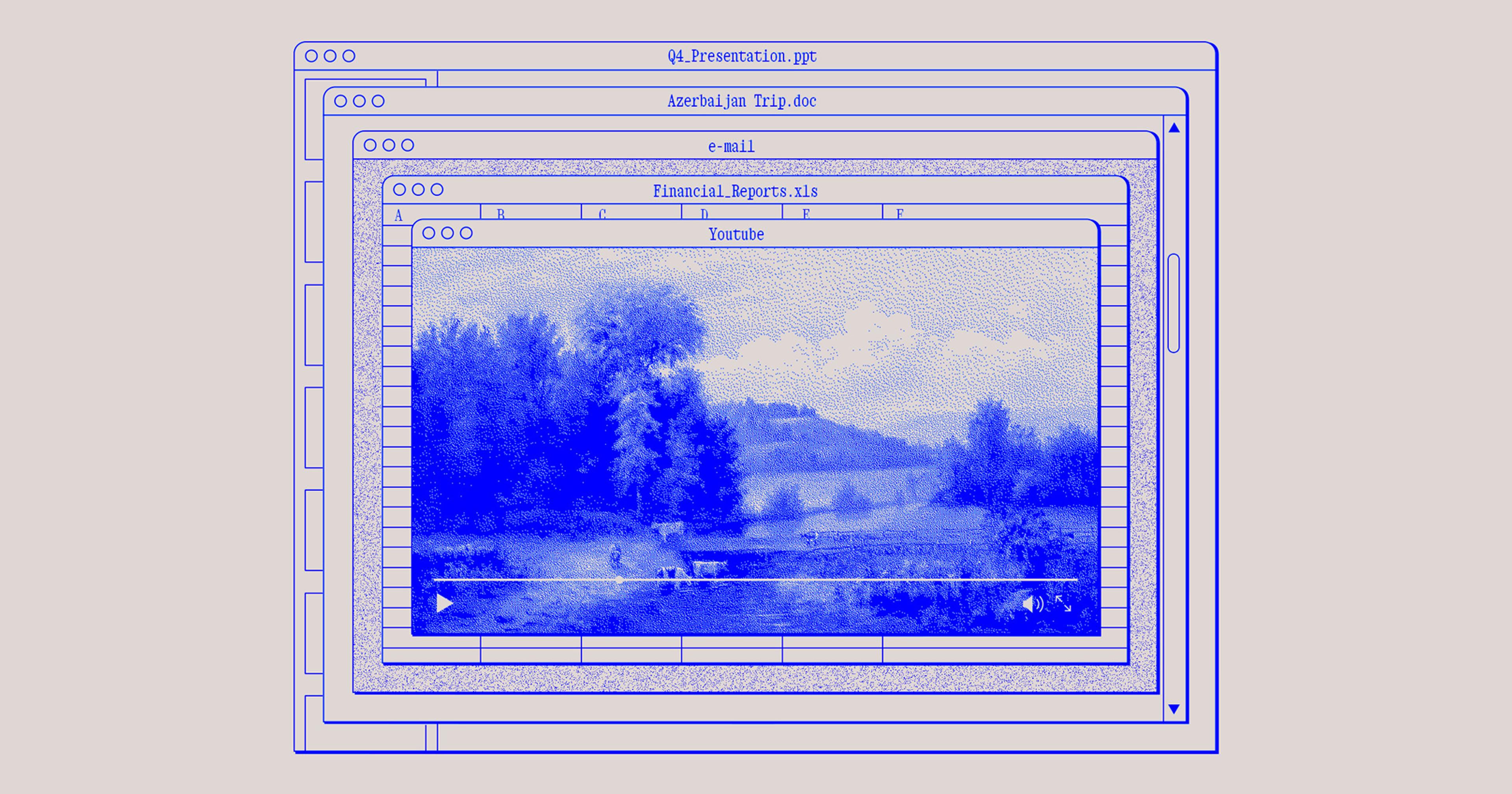

Still from Become a Farmer

The CCP has trumpeted the show’s success, writing in an op-ed in the Communist party newsletter, “From sowing and irrigating to fertilizing and harvesting, they are no longer celebrities, but true farmers that rely on nature for their livelihood. This affects every single viewer, and allows audiences to more intuitively understand the importance of food, to cherish food and cherish life.”

Meanwhile, China’s American Farm Style mimics a mythical American agriculture sector that exists primarily in the popular imagination. Yin Muchuan, a platinum-blonde creator and self-described “outfit sharer,” plays dress up in his version of the American Cowboy 美国牛仔 aesthetic, complete with a makeup-drawn face of freckles. A silver star reading “sheriff” decorates his tan cowboy hat, and he pairs a denim shirt tucked into wide-leg black and white cow print jeans. American Farm Style fits within the larger trend of America Core, presenting the imagined version of a faraway lifestyle. America Core appears in Muchuan’s other posts, where he dresses up as a McDonald’s server or poses in front of an Ikea sign.

But just like actually working at McDonald’s may not be so glamorous, real farmers in the U.S. face unprecedented challenges today. According to the USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture, from 2017 to 2022, the number of U.S. farms decreased by 141,733, nearly 7%. Additionally, since 1982, urban expansion has decimated American agricultural land by more than 31 million acres. Meanwhile, farmers on the ground are dealing with everything from climate disasters to corporate consolidation to general financial hardship.

Influencer Yin Muchuan displays American Farm Style

Unsurprisingly — and similar to China — it’s a struggle to convince enough young Americans to enter the field. A future shortage of new farmers looms; the 2017 Census of Agriculture found that farmers 35 or younger only make up 9% of the nation’s 3.4 million agricultural producers. Though they may not have official government backing like their Chinese counterparts, some U.S. social media stars see their platform as an indirect recruitment tool for new young farmers.

Morgan Shaw of Gold Shaw Farm in Peacham, Vermont, boasts more than 2.2 million TikTok followers. Obviously his platform helps him make a living, but Shaw also hopes his videos can convince more young people to heed farming’s call. “If I look at my audience, many are younger and getting their first exposure to agriculture and farm animals,” he said. “For most, it’s escapism, but for others, it fuels a passion, getting them to want to start raising their own ducks, cattle, or start gardening.”

Chinese farming influencers are but one of the government’s means to bolster food security and rural revitalization, but they’re clearly seen as important. Even Pay, an agriculture analyst at the research and advisory firm Trivium China, told the Los Angeles Times, “Policymakers are going to use every single tool in their toolbox to make sure China continues to have ample food at a reasonable price. Part of that is persuading young people to pursue a career in agriculture.”

And China is surely seeing some dividends from this public relations push. The L.A. Times reported that the number of young Chinese people going into agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, or fishing climbed from 1.2% to 1.9% in 2022, an increase of more than 200,000 people. Anecdotally, stories like this one from France’s press agency have been showcasing a trend of urban Chinese millennials leaving their day jobs to pursue careers in agriculture.

Despite differences in presentation and approach, farm content creators in China and the United States are both helping foster a new generation of potential, first-generation farmers. “Which, at least here in the United States, is something we very much need,” said Shaw. “We need our best and brightest going into farming. And if content like mine can influence the next generation to do that, I’m so happy to see that happen.”

Meanwhile, a tea farmer in China who uses the social media handle Countryside Vending Machine makes a pitch to his followers: “Maybe you will find your original self and the courage to start anew.”