Outpaced by farmers with access to modern technologies, the Amish community has produced the first new horse-drawn combine in nearly 70 years.

“You know, with all the ponies we have here this morning, they’re doing a super good job,” the announcer sings out, as a parade of children drive miniature ponies around a paddock. “We got some of the best horsemen of the future in the ring this morning. Horsemen of the future!”

The horsemen of the future have ponies named Sparky, Pepsi, and Snickers, which, the announcer tells us, they earned by saving tips from the market, or got as gifts from their parents for not eating candy. They are Amish and Mennonite children, whose families and parents and communities sit around the paddock, applauding them as they drive by.

This is the opening event of Horse Progress Days 2024. Now in its 30th year, Horse Progress Days (HPD) is an annual two-day event dedicated primarily to demonstrating horse-drawn technology. Of the estimated 20,000 attendees this weekend, some 60 to 70 percent are Amish or Mennonite — otherwise known as the “Plain community” because of their simple garb.

HPD wasn’t founded by the Plain community, nor exclusively for them, but it has become an event dedicated as much to horse-based farming as it is to encouraging the next generation of Amish and Mennonites to keep working in agriculture.

There are fewer and fewer farmers in the Amish community — recent estimates suggest only around 40% of the Amish households in Lancaster County are farming, a decrease of 27% over the last fifty years. As event organizer and Amish farmer Stephen Esch put it, “It’s important for us to be very inspiring, to inspire the younger generation, that, hey, this is a way of life, it’s worth your time and effort to grow food.”

I can see it working, too. Watching a farmer named Junior Blank pull a manure spreader with a team of four mules, the announcer tells us Junior was a spectator at the first-ever Horse Progress Days in 1994. Blank remembered thinking, “‘You know what, this would be my dream someday to drive a team in Horse Progress Days,’ … and today, he is living the dream.”

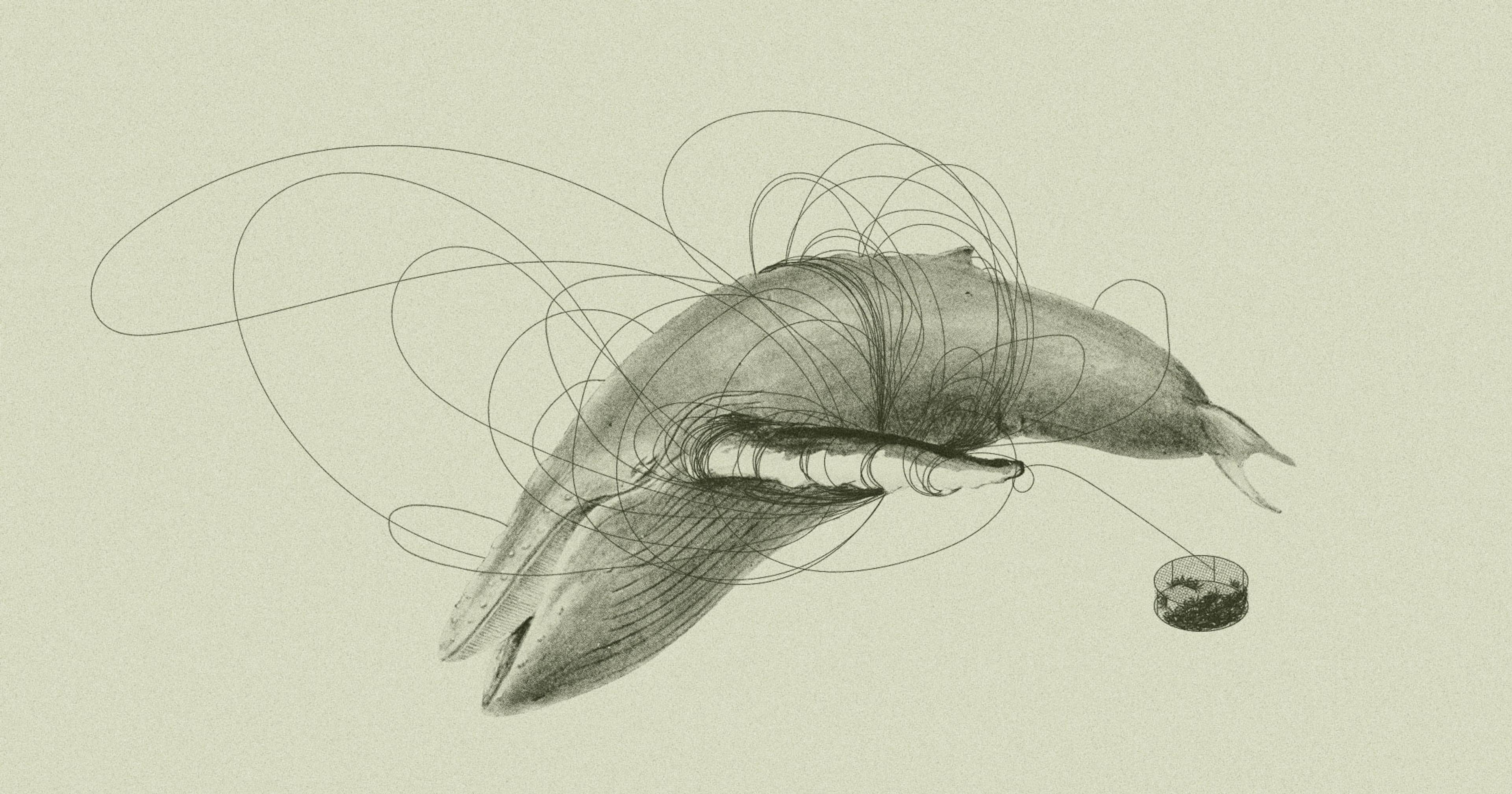

Jonas Stoltzfus’s combine preparing for the demo.

The inspiration is direct too: Along with typical HPD fare like manure spreading and breed presentations, this year also features lectures and seminars such as “Elements of Successful Farming Communities,” “Inspirational Farming: How Can We Embrace the Times?” and “Continuing Goat Farming into the Next Generation.”

The drive for inspiration is why, this year, everyone is excited about Jonas Stoltzfus and his horse-drawn combine harvester. It’s the first new horse-drawn combine created in some 60 to 70 years. It’s so new that it doesn’t even appear in the events scheduling, since no one was sure if it would be ready for demo.

“This is what Horse Progress is all about,” I hear on three separate occasions, from three different people. Stoltzfus’ combine is both a major innovation in horse-drawn farming technology, and a way for new generations of Amish to maintain viable farming businesses.

Nina White of Bobolink Dairy & Bakehouse lectures on “Baking with Local Grains” in the Homemaker Seminar Tent.

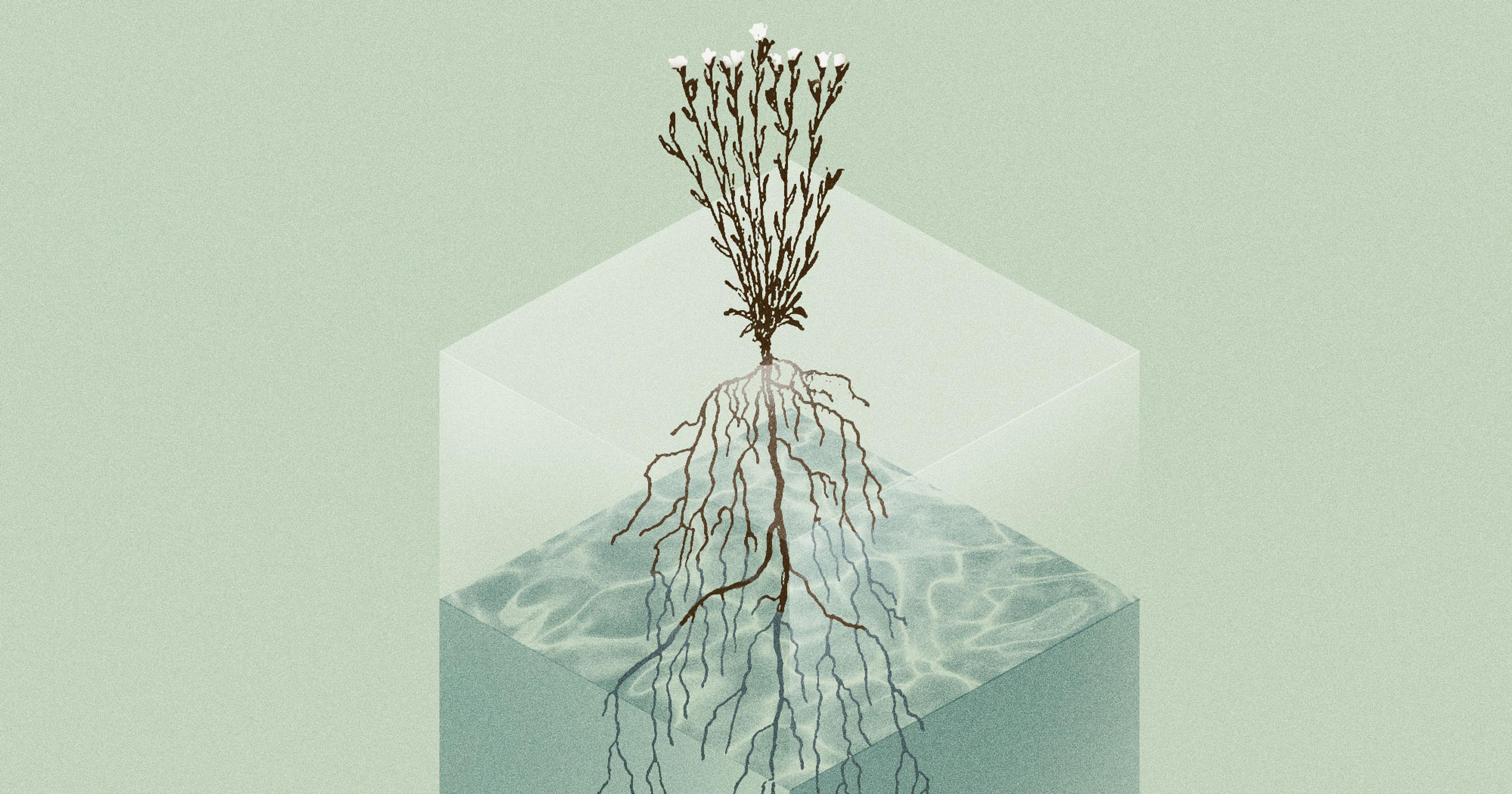

While old horse-drawn combines are still operated and maintained by Plain farmers, they were designed for much lower crop yields per acre than contemporary agriculture can produce. More and more, some Amish and Mennonite farmers have been contracting non-Plain farmers who own self-propelled combines to harvest their fields (permitted based on their local church’s rules). It’s a practical, economic decision, essential for many farmers to be viable; it is also a small but significant erosion of the communal spirit so essential to Amish life. And this is why Jonas’s new combine is, in a sense, an existential effort.

As event organizer Dale Stoltzfus (no relation to Jonas) puts it, it’s a question of if “the big combines coming down the road for eight dollars an acre will win, or … if a couple farmers go together and buy a $30,000 machine [such as Jonas’s] and then work together and do their neighbors’ wheat and so on. Maybe that will win out. I don’t know. But Horse Progress Days is a place to experiment with these kinds of things.”

From a distance, what appears to be an exercise in paradox and anachronism is in fact a petri dish for how an oppositional society survives in a changing world, especially in practical, economic terms.

Lot 29 in the Pony Parade, pulled by miniature pony Angela, a two-year-old

fusion mare.

Plain community ethos begins from the biblical passage Romans 12:2, “And be not conformed to this world.” Separation from society — and the state — is an essential element of how they move through the world. Case in point: HPD 2024 takes place on the Wireless Valley Farm, so named because the Amish farmers who run the land have kept it off the electrical grid.

That doesn’t mean the Amish and Old Order Mennonite don’t use electricity though. Plain communities sometimes use solar panels or gas-powered generators. In what scholar Donald B. Kraybill calls “the riddle of Amish Culture,” new technology is approved or rejected on a case-by-case basis that can appear confusing to outsiders. For instance, while self-propelled locomotion is prohibited, some young Mennonites have underglow LED lights on their buggies. And horse-drawn farming equipment often includes a gas engine to power the rest of the mechanics, as seen frequently at Horse Progress Days.

Community leaders arrive at these decisions by balancing separation from society with the economic and cultural appeal of a given technology. There’s no overarching Amish or Mennonite governing body either. Each local church determines its own ordnung, or rules, that define the boundaries of their world. As Kraybill writes, a successful ordnung allows a community “to worship together and to commune secluded from the world.”

Plain community youth enjoying a game of volleyball.

This seclusion is readily apparent at Horse Progress Days. Except for business and lectures, there’s a high degree of separation between Plain folk and the rest of us. Weaving through the crowds, the main language spoken is Pennsylvania Dutch, a dialect of German that hardly anyone outside their community speaks. Many Plain folk firmly decline to be interviewed. Of those who do agree to speak to me, I feel an intense wariness, a factor of their being “not conformed to this world.”

They also all ask me who I’m writing for before they agree to speak, surely due to the Cosmopolitan and Type Investigations report from 2020 that detailed cases of silenced and unprosecuted rape and incest in Amish communities. I also don’t manage to have a single conversation with a Plain woman — perhaps because the subservience of women is another common ordnung. The fact is that the rules that maintain their unique and, in many ways, admirable way of life are the same that can actively dissuade people from addressing and preventing inequity and sexual assault.

Still, despite the marked uneasiness between communities, everyone’s having a good time. Vincent, a French Canadian man working with a camera crew, tells me it’s the best day of his life. When a piece of manure flies into a Mennonite announcer’s mouth during a manure spreading demo, he earnestly praises the smell. At a horse-drawn stake-pusher demo, another announcer comments that it “almost makes you want to grow an acre of tomatoes just for the fun of it.”

Homesteading Seminar Tent schedule for the weekend

As well as a technology expo, it’s also a flagship social event that people look forward to all year. Amongst the demo fields, paddocks, and lecture tents, there are also volleyball courts, horse-drawn train rides, and a petting zoo.

Horse Progress Days has evolved a lot from where it started. It was founded in 1974 by Elmer Lapp, a Belgian breeder, and Morris Celine, who founded the magazine Draft Horse Journal. Neither were from the Plain community, but they wanted to create an event for the outside world to see what that community was doing with animal-traction farming. (Mules and oxen are also welcome.) Since then, HPD leadership has become almost entirely Amish and Old Order Mennonite. And while its core mission is still “to demonstrate newly manufactured horse drawn farming equipment behind real horses in real field conditions,” it has equally become a moment to celebrate the Plain way of life.

The event organizers made it very clear to me, though, that they don’t want this to become a big tourism event where people come to ogle the Amish and Mennonites. At its core, it should always be about horses and progress.

Horse progress really takes on meaning at the wheat field at 1 p.m. on Saturday, where Jonas Stolfetz will finally demo his combine prototype.

A member of the East Coast Horse Association demonstrates how to break a colt.

The long, narrow strip of unharvested wheat, near the buggy parking lot, is packed three to four rows deep with guests. The announcers, speaking from a Conestoga wagon, are effusively praising the coming attraction, and speculating on “the property this makes possible.” I look out over a sea of straw hats and bonnets to see Stolfetz and his team readying the eight matching mules it takes to pull this machine.

There is a few minutes’ delay when one of the mules falls over, and again when the engine battery dies. “It takes a lot of gumption to bring a new machine out here,” an announcer says, “because it can always fail at the last minute. And I commend these guys … and just say thank you.”

And then the engine is up and running, the mules are ready, and Jonas leads his prototype into the wheat. The mules bow their heads in effort. The machine is whirring so loud it drowns out the commentators. As it catches the first rows of wheat, it churns up huge clouds of dust and chaff behind it. Half a second later, it starts spitting grain out of the unloading pipe in a steady, powerful stream. It’s a success, and there’s a palpable release in the crowd.

As I take photos, an older Mennonite man hands me a note card with his email on it and asks if I can send them to him. At his church, they can use self-propelled combines but not cameras. He hasn’t seen something like this since he was a young boy, and he wants to remember it.

“What a sight, what a sight…” the announcer cries out.