After more than a decade of greening disease devastation, Florida’s citrus farmers are considering alternative crops. One company claims they have what it takes, but farmers are skeptical.

When citrus greening — a devastating bacterial disease — swept through roughly 2,500 acres of John Paul’s citrus groves in Central Florida, he likened the effect on his crop to a more human disease.

“It’s like an AIDS or something,” he said. “It really bogs a tree down and then something else comes and kills it; it’s just in a weak state.” The greening made it so his trees just couldn’t stand up to the “couple hurricanes, some freezes, and droughts” that also hit his acreage in the last two decades, and will only continue to grow more regular and destructive because of climate change. While the damage of Hurricane Milton, which tore through Central Florida this season, is still being assessed, the Florida Farm Bureau estimates Hurricane Ian caused close to $250 million in citrus losses alone in 2022.

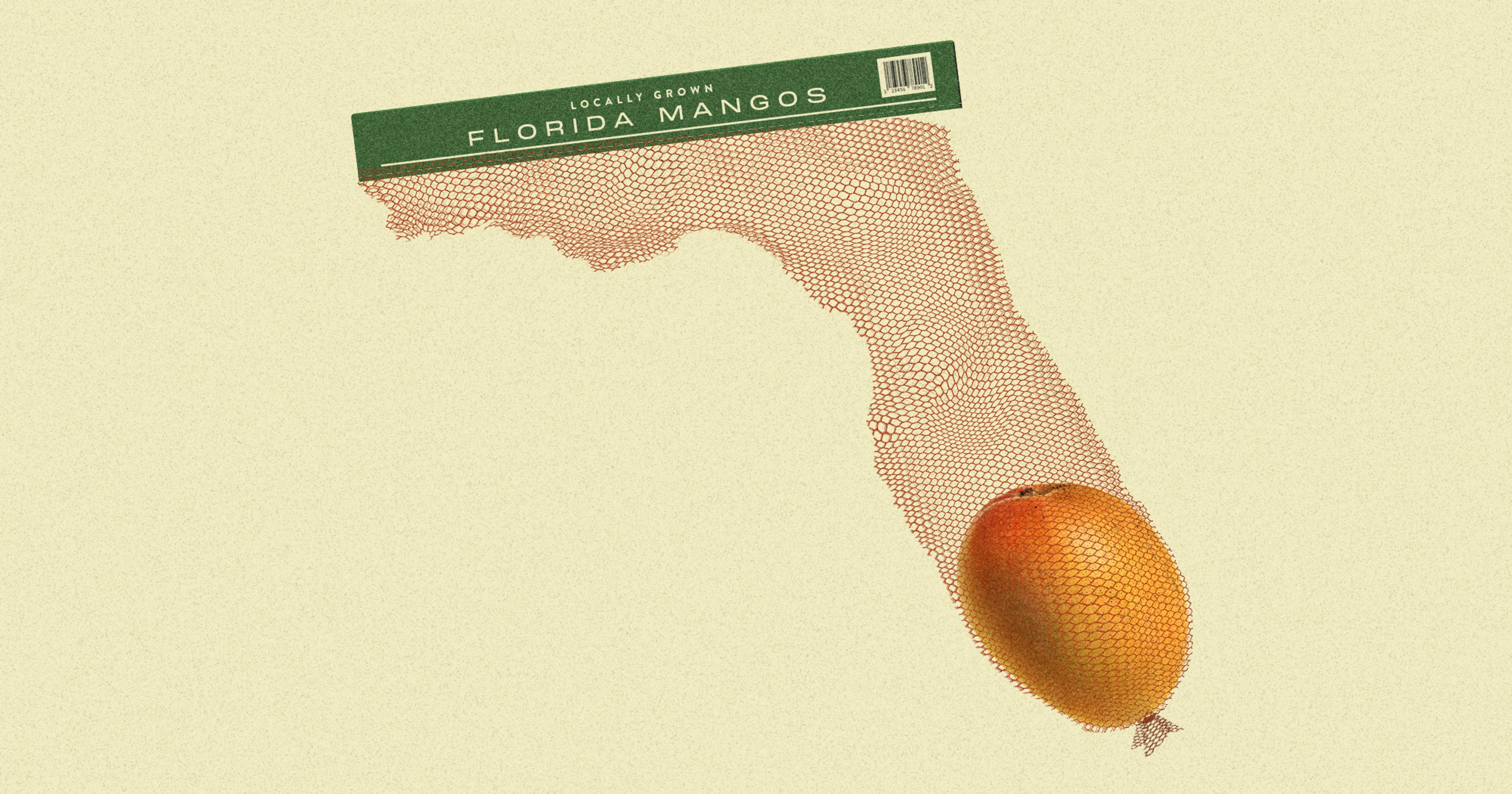

The greening wave has left Paul little choice but to convert large chunks of his total 8,000 acres to pasture land. While he only has 400 acres currently in production, he has about 4,000 available for experimental planting of greening-resistant crops, a new fixation of his. “We’re trying to figure out stuff to survive,” he said. He’s planted all sorts of things, from red and green guavas to olives and a lychee-like fruit called a longan. He’s also looking into a South Asian evergreen tree with leaves that are used to make kratom, a stimulant that some researchers suggest might help wean heroin addicts off the drug.

In the scramble to find a viable replacement for citrus, farmers like Paul have searched high and low. Agriculture entrepreneurs have sung the praises of countless miracle crops — everything from bamboo to hemp — that have mostly failed to take off. But about 10 years ago, Paul learned of a subtropical “super tree” called pongamia that grows throughout in other countries with similar climates to Central Florida. He read lots of studies out of Australia about these pongamia trees: their hardiness, their adaptability, and the beans they produce, which can be processed into biofuel or high-protein foods for people and cattle. He reached out to the Ministry of Agriculture in India to get some pongamia seeds, and they were “very happy” to provide.

Since that time, pongamia trees have found a champion in a company called Terviva, a California-based agriculture venture that has been busy pushing it as yet another miracle plant that can not only resist greening but is “climate-resilient” and “helps to reforest land and revitalize communities,” according to the company’s website. This summer, a swirl of Terviva press posited that pongamia may be the answer to greening-related citrus decline in Florida.

“As large parts of the Sunshine State’s once-famous citrus industry have all but dried up over the past two decades ... some farmers are turning to the pongamia tree, a climate-resilient tree with the potential to produce plant-based proteins and a sustainable biofuel,” per the Associated Press.

But Paul and other Florida citrus experts are skeptical.

Ray Royce, executive director of Highlands County Citrus Growers in Florida, wonders if pongamia isn’t just another buzzy gimmick like bamboo, which recently enjoyed a glimmer of popularity in the state but was never able to establish a solid market.

“[Citrus greening] really bogs a tree down and then something else comes and kills it, it’s just in a weak state.”

“You start talking about the bamboos and pongamias of the world, there isn’t infrastructure,” Royce said. “It’s hard to be the guy who says we’ll spend thousands and thousands on an acre with just the hope that someone will put in the necessary processing facility.”

Royce said that before farmers buy into pongamia on a mass scale across thousands of acres of former citrus land, there needs to be a guaranteed market. As of now, Terviva hasn’t been able to demonstrate that there is one.

Royce has been in touch with Terviva representatives, and asked to speak with some of the growers who have purchased Terviva’s trees and whose product Terviva has processed. “I’m interested to know how profitable per acre their product is versus other agriculture,” he said. But he’s never gotten an answer. (Neither have we: Terviva representatives declined to comment, and top investors did not return multiple phone calls.)

As for Paul, his early investment in pongamia hasn’t paid off. What started as several dozen acres of pongamia is down to five or 10, he estimated. And while the remaining trees have “grown beautifully” — some of them up to 80 feet tall — he’s never been able to find a market for the nuts, even 10 years in.

“There’s a lot of stuff you can grow here, but unless you know you can make money at it, then people aren’t gonna plant hundreds or thousands of acres,” Royce said.

He assured me he wasn’t just being stubborn. He’s not an “only citrus” kind of thinker, and as painful as it may be, most citrus growers aren’t against finding alternatives either, he said.

“It’s not that I’m thinking that this will never replace citrus, or that citrus is king. It’s not that.“

“I hope that either this or something like this comes around. By me being more skeptical, it’s not that I’m thinking that this will never replace citrus, or that citrus is king,” he said. “It’s not that.”

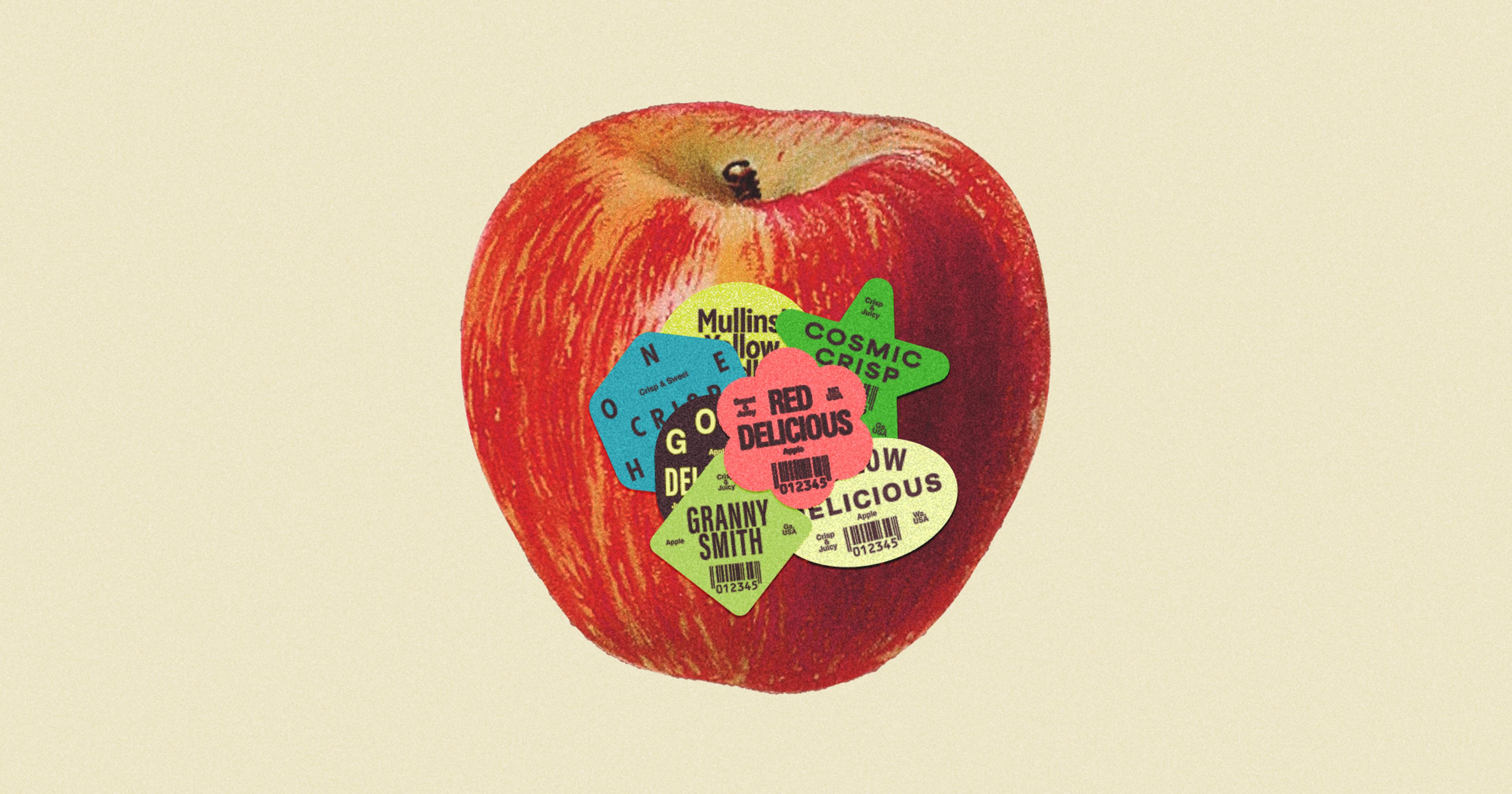

But citrus does have deep roots in this part of the country that long pre-date this greening epidemic, explained University of Florida citrus extension specialist Tripti Vashisth.

Much of her focus at UF is on horticultural strategies that will help greening-affected trees stay productive. “Many growers are at least third or fourth generation,” she said. “They are passionate about citrus and that’s what they want to do because it’s their family legacy. There’s a lot of growers who want to keep citrus in Florida. We want this crop to work here because it has worked for centuries.”

But greening, a bacterial disease spread through bites from an insect that feeds on a tree’s leaves, is a particularly devastating force. It ravages the trees from the inside, coursing through the circulatory system and prompting counterintuitive defenses, like halting the movement of sugar to its fruits. The result is nasty, commercially non-viable citrus.

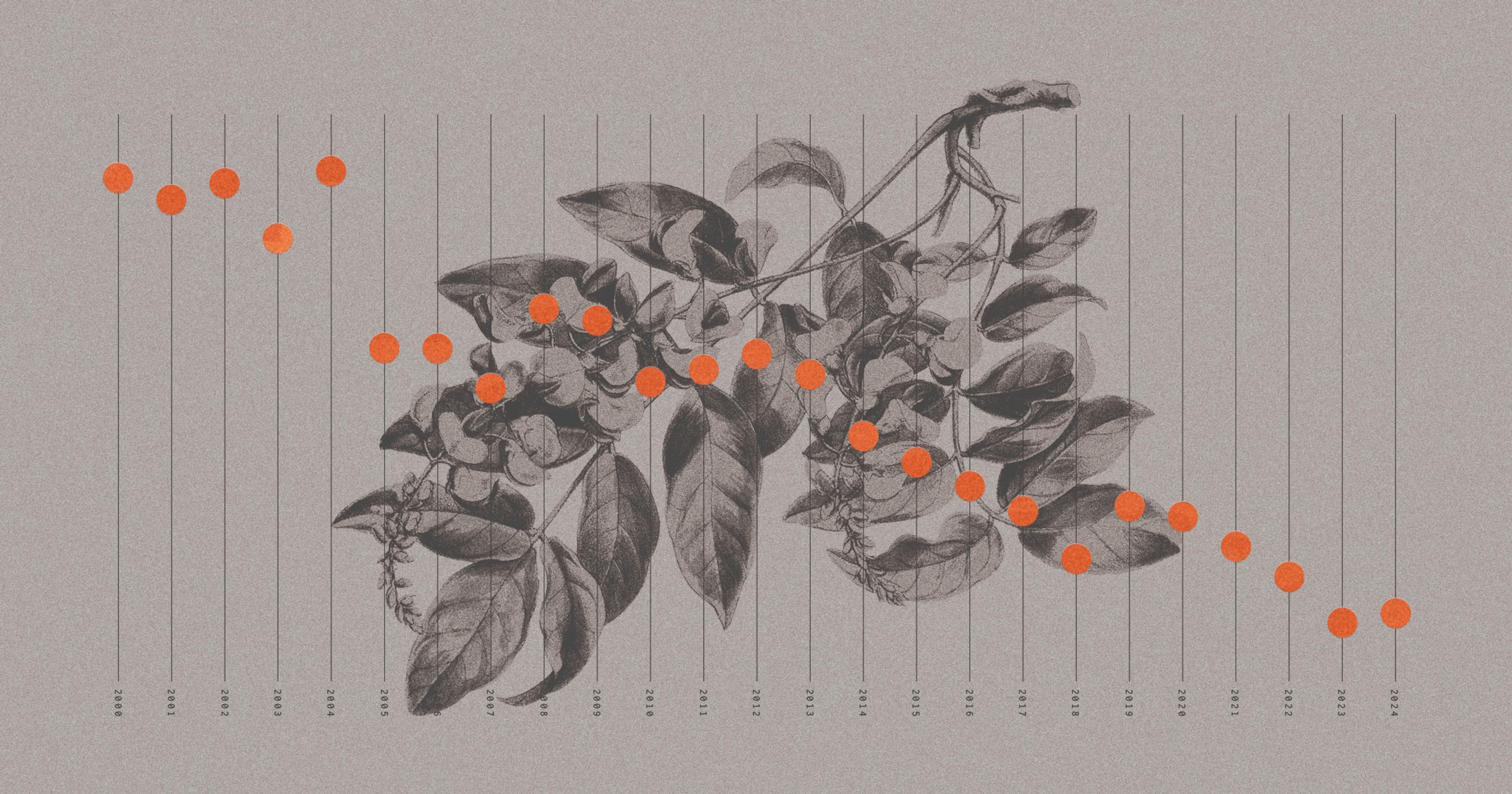

The AIDS comparison isn’t such a wild exaggeration, according to Vashisth, because the disease zaps a tree’s energy needed to fight infection. Also like AIDS at its peak, “the disease is everywhere” — since it was first detected in Florida in 2005, virtually every grove in the state’s heavy citrus regions has become infected in the first year of planting. Overall, it’s estimated Florida’s orange production has fallen 92 percent in 20 years because of disease and natural disasters.

“Our growers are kind of stuck with what they have and that’s the problem.”

If pongamia turns out to be the silver bullet Terviva claims it to be, Florida’s citrus country would welcome it with open arms and fields. But no one is willing or able to prove that just yet.

The articles that circulated earlier this year imply that pongamia is currently being produced and processed on a large scale in the U.S., though it’s been years since Paul, Royce, Vashisth, and other contacted experts have heard much about pongamia production in Florida. “My intuition says there are possibly some challenges,” Vashisth said, though no one knows for certain what they are.

Whether it’s pongamia, bamboo, hemp, peaches, or hops, a tree crop won’t have the sweeping impact anyone hopes for until there’s investment in production infrastructure.

“Citrus is an evergreen, perennial crop, and you expect the trees to be productive for at least 20 years if possible,” Vashisth said. A similar kind of disease would never be as devastating to something like a potato, because you start each season with a new crop. “But our growers are kind of stuck with what they have and that’s the problem,” she said.

Royce put it another way. “A tree crop is like getting married, not a long weekend date,” he said. Before they tie the knot, farmers need to know what they’re getting themselves into.