Many farmers in Kentucky were dazzled by eye-popping prices and potential for growth in the newly legal industrial hemp business. It seemed too good to be true — and it was.

In April of 2019, Senator Mitch McConnell took a victory lap around his home state of Kentucky. In photos posted to Twitter by state agriculture commissioner Ryan Quarles, McConnell grinned widely as he toured the facilities of GenCanna, one of many companies that had sprung up to process hemp into profitable CBD extracts. The state began exploring commercial cultivation in 2014; five years later, McConnell had helped make hemp federally legal, and he was busy touting its limitless potential. In a speech that day, Quarles thanked McConnell for “making hemp great again,” and in an accompanying press release McConnell is quoted as saying, “I knew Kentucky would be at the forefront of hemp production. It didn’t take long for GenCanna to prove me right.”

Hemp was flying high, but it was about to come down hard. Eight months after McConnell’s triumphant event, GenCanna was being sued by farmers who said it owed them $13 million in back payments. In January of 2021, it was involuntarily placed into bankruptcy and had its assets sold off to pay creditors. And GenCanna’s story isn’t unique.

As the bottom fell out of the hemp market over 2019 and 2020, companies with names like Bluegrass Bioextracts and Elemental Processing also faced massive class-action suits, liens, and bankruptcy, amid allegations that they hadn’t properly paid the farmers they contracted with. Then of course, there are the farmers, who took a big gamble on a crop that was a big loser for many.

Before the collapse, farmers had signed contracts with processors for as much as $40 per pound of hemp. After the smoke cleared, the lucky ones were able to sell their crops for one dollar per pound. Kentucky farmer Bobby Huff estimated that he lost a total of $120,000 farming 10 acres of hemp. In the end, he ground up much of it to feed his cows.

What happened? How did so many people go broke selling hemp?

The New Tobacco

Given its close ties to marijuana, hemp is in many ways an unlikely cash crop for a conservative state like Kentucky. Indeed, lawmakers like McConnell were hesitant to support its legalization because they didn’t want to be viewed as soft on drugs. Joseph Hickey, an activist and entrepreneur who’s been working on legalization since the 1990s, remembers McConnell saying: “I can’t even be seen with you. Everybody’s going to think I’m trying to legalize marijuana.”

What exactly is the difference? According to the USDA, the only way to legally distinguish the two is by measuring the level of the psychoactive chemical THC. Anything above a concentration of 0.3% is marijuana, and anything below is hemp. (Cannabidiol, aka CBD, is the second-most prevalent active ingredient in marijuana, but is also present in hemp.) Anecdotally, advocates will say hemp is hardier, grows more easily, and has plants of a slightly different shape. Historically, hemp is a simple crop which has been used to make rope and cloth for much of human history. Marijuana is its fussier, newer cousin — imagine the difference between a traditional, low-alcohol beer and a 12% ABV microbrew you can now find in artfully decorated cans.

Kentucky was uniquely involved in the legalization of hemp, and uniquely impacted by its downfall, for one simple reason: its longtime reliance on tobacco, a crop once central to the state’s economy that was badly in need of replacement. Since the federal government ended its price support and quota system for tobacco in 2004, its profitability has been in freefall. According to an analysis by the University of Kentucky, tobacco farmers’ expected returns per acre have declined from roughly $1,000 to just $100 over the past 20 years.

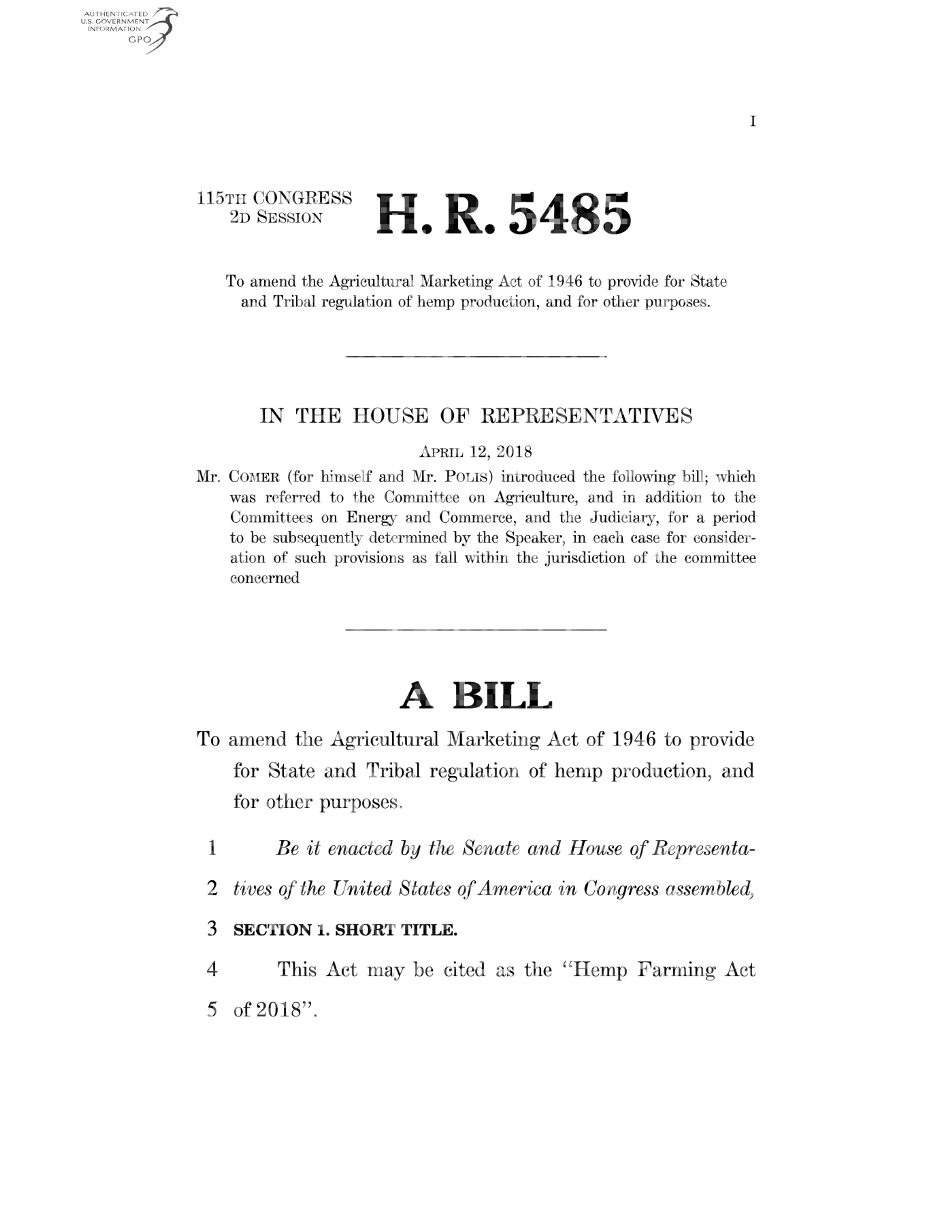

Advocates saw hemp as a solution. It grows plentifully in Kentucky’s climate and, in a seemingly fortunate twist of fate, utilizes almost exactly the same machinery and processes as tobacco. As calls for legalization grew louder, and organizations like the politically conservative American Farm Bureau joined the cause, more politicians saw the benefits. Some credit Rep. James Comer (R-KY) with winning over McConnell, who put language into the 2014 farm bill allowing states to establish pilot programs to study the industrial production of hemp.

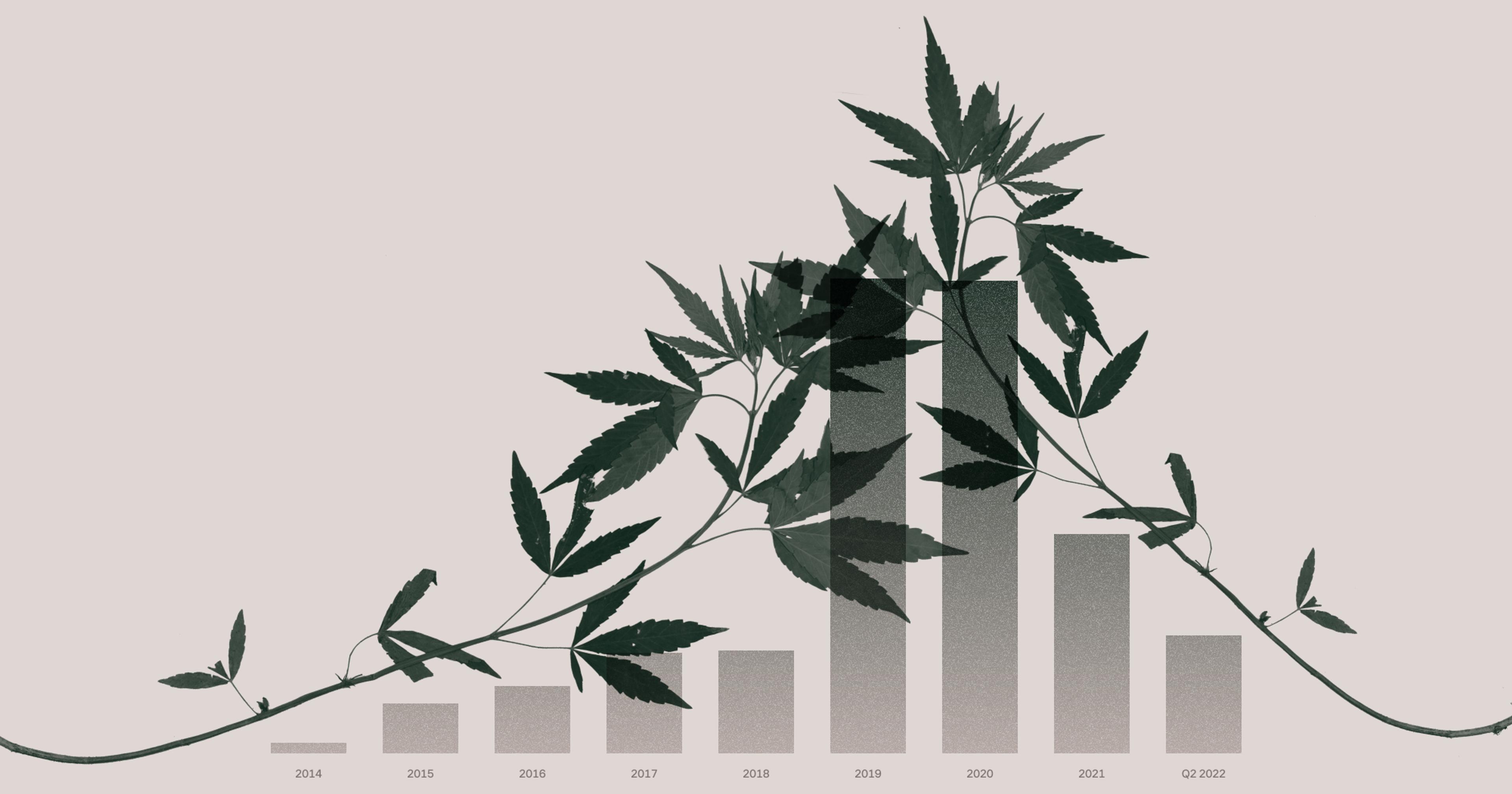

Kentucky was one of just four states to begin its program in 2014, alongside Colorado, Indiana, and Vermont. (By 2018, the total of states studying hemp production had grown to 22.) In the Farm Bill’s 2018 iteration, Congress removed hemp from the DEA’s schedule of drugs, freeing it from stringent oversight and clearing the way for widespread farming. And, it seemed, they’d done it just in time — in 2017, the CBD industry was worth $350 million and looked poised to continue its rapid expansion.

Just before the pandemic, America had a brief but passionate affair with this low-THC cannabinoid extract that’s supposed to deliver the relaxing and pain-relieving effects of smoking pot without actually getting you high. Its specific benefits could be hard to pin down, but that didn’t stop its groundswell of popularity; as one meme account memorably described CBD: “It’s like weed but it doesn’t work.” For much of 2019, it felt like every cafe was offering CBD lattes and every local wellness place briefly replaced its crystals with CBD creams. A combination of popularity and relative scarcity drove extract prices through the roof, promoting wild speculation in the space.

Jumping into something relatively unknown like hemp was an easy decision for farmers like Huff, who followed his father and grandfather into running a diversified mid-size farm spanning several kinds of crops and livestock. “The farming landscape’s been pretty tough,” he said. “The cattle market’s been in the shitter for probably six, seven years now. I was in the chicken business, I had broiler houses and they were struggling … nothing’s great.” When asked what attracted him to the hemp business, he laughed dryly before saying, “Just the sheer money.”

“It was always a gamble, but the money was prospectively really good, and we had the chance to get in on the ground floor of something and figure it out before everybody else did,” said former Kentucky tobacco farmer Taylor Jones, explaining why he first decided to grow hemp.

“If you talk to these farmers about growing hemp again, they’ll run you off the farm.”

And a gamble it was. In 2019, tobacco was selling for a little over $2 a pound, according to USDA data, whereas hemp was contracting for as much as $40 per pound. For many like Huff, deciding which crop to plant was easy. More than 1,000 farmers were approved to farm 60,000 acres of hemp in the state that year, a 460% increase in number of farmers over the previous year and a 370% increase in acreage.

Up in Smoke

Problems began to show almost immediately. In a clear-eyed analysis of the nation’s various pilot programs, a USDA report wrote that “most States had fewer than five people to implement and oversee the pilot programs … this creates challenges in supporting a new industry with elevated regulatory and reporting standards.” In other words, the burden of handing out hundreds of licenses, verifying the THC content of tens of thousands of plants, and advising many hundreds of interested farmers was being handled by fewer people than are usually behind the counter at an Apple store. According to the same report, Kentucky’s 1000 hemp farmers and 200 processors were overseen by just three full-time and two part-time staffers. Even at this low level, Kentucky actually had one of the country’s better-staffed programs: Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin all had no full-time employees.

In some ways, oversight of the industry was minimal, but in others it was onerous and bureaucratic. A state spokesperson confirmed that there were no bonding requirements for processors, who were only required to pay a fee of at most $3,000 (and in many cases only $500) before they could begin granting multimillion-dollar contracts. In other words, they weren’t required to carry any type of insurance guaranteeing they could actually pay out the money they promised. There were no limits on the number of farmers who could grow, and no limits on the amount of hemp they could produce. But in order to prove their crop was below the legally required 0.3% THC levels which separate hemp from marijuana, a state representative had to visit a farm, take clippings, and verify their THC levels — reasonable in theory but difficult in practice, according to Hickey.

“It takes control out of the farmer going, ‘Okay, this is the perfect time to harvest. We need to start today or tomorrow.’ But before that, you’ve got to call the state, and they say, ‘Well, we can’t get out there for two weeks,’” said Hickey. “Then you’ve screwed everything up.”

At the same time, the state was actively promoting the industry to farmers, though often with a note of caution. “These warnings informed applicants about the unstable market and the risk of new companies and buyers. Applicants were advised to not invest any more into this new industry than they could afford to lose,” said a Kentucky Department of Agriculture spokesman.

Some farmers, like Jones, tried to remain cautious. “There were a lot of people that had literally millions of pounds contracted at $40 a pound,” he said. “And you’re sitting there evaluating, you see [a processor] has never done any business, never created millions of dollars worth of sales, and you’ve got $40 million worth of liability coming this fall?” It didn’t seem like a wise gamble.

According to Keith Rogers, chief of staff at Kentucky’s Department of Agriculture, recent analysis shows that farming around 80,000 acres could supply the entire United States with enough CBD for the current market. At its peak in 2019, according to the USDA, there were more than 146,000 acres of hemp planted in the United States, with 26,000 in Kentucky alone — though some argue the nationwide figure was undercounted, and in fact could be up to five times higher.

“We were growing enough CBD to last every man, woman, and child in the whole United States for 10 years,” said Hickey.

According to industry group Hemp Benchmarks and as reported by Cannabis Business Times, in the year between spring 2019 and spring 2020, prices for hemp CBD biomass declined by an eye-popping 79%. As these prices cratered, the choke point in the system turned out to be processors who could turn a hemp plant into CBD oil. They’d promised astronomical sums to farmers, but suddenly found themselves unable to actually sell at a price which would allow them to pay what they owed. They suddenly needed extra time to take delivery, found mysterious contaminants, or, worst of all, simply took farmers’ crops and never paid.

“Processors were leaving the state, going to states where they could do more, or they were threatening to leave the state,” said Katie Moyer, owner of processing company Kentucky Hemp Works and president of the Kentucky Hemp Association. “Sometimes we would see bad actors that just left the state because, well, Florida legalized medical marijuana and they were gonna go down there and try to cash in on that. And they just left our farmers holding the bag.”

This overproduction certainly tells part of the story of hemp’s collapse, but not all. Rogers and others in state government point fingers at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which never established a formal framework for selling and regulating CBD. This left the market unstable and unattractive to major corporations, according to Rogers. “They’re not going to go down this road until FDA acts,” he said, obliquely referring to major companies who might otherwise market CBD oils, lotions, even drinks. At the same time, consumer demand for CBD never quite met projections. “Whatever percentage of the public who are open to trying or regularly taking CBD, obviously, that group is much, much smaller today than predictions were back in ’17, ’18, ’19.” Even reputable processors, he argued, couldn’t meet their contracts because they weren’t making the sales to support them.

“Unfortunately the consumer demand did not increase at the same rate that the excitement to grow this plant increased,” said Kentucky Hemp program manager Doris Hamilton in a video presentation for the University of Kentucky’s Hemp Field Day on Dec. 8, 2020. “Exactly what the true demand is, we don’t know yet. This is an industry that’s still in its infancy.”

“The bottom just completely and totally fell out,” said Jones. “A lot of guys invested $10,000 an acre into growing the stuff. At a hundred acres, that’s a million-dollar investment. If you don’t bring anything in on that, it’s a pretty serious situation.”

Unsurprisingly, this has severely suppressed the once-ravenous appetite for jumping into Kentucky’s hemp industry. In 2021, the number of farmers applying to grow hemp fell by more than 50%, to just 450. In 2022, the number fell further, to 240. By 2022, approved acres plummeted from their 2019 peak of 60,000 to 5,530.

“It’s a black eye, I think, for the farming industry in general.”

“You can talk to any of these farmers that grew hemp,” said Hickey. “If you talk to them about growing hemp again, they’ll run you off the farm.”

Industry advocates point out that this is a lightly regulated developing industry, and with proper direction it will continue to grow.

“Really I do think that things are getting better,” said Moyer. “If you ask around in the industry here and you ask them, how did you get through the last two years? They’ll tell you by the skin of my teeth with bubble gum and glue. It’s not like we are coming out on top like champions, but also the ones who survived are still here, still trying to do a great job.” When we spoke, her organization was celebrating a victory against the state in the battle over Delta-8, a more intoxicating variety of hemp the state was fighting to keep illegal. She now calls Delta-8 the “biggest growth market” in hemp.

“The demand’s still there! People are still buying,” said Hickey, pointing out that a brand called Charlotte’s Web was recently named the official CBD of Major League Baseball. “There’s just fewer [farmers] that had the money to withstand this crash.”

Huff, for his part, said his hemp crop was “a total loss.” He ruefully remembers a conversation with his brother from just before he began cultivating hemp. To his brother’s suggestion they only grow one test acre, Huff said, “Dude, we’ve got a contract. The state is promoting the crap outta this thing.” He was sure the processors had been vetted and “could pay their bills if it didn’t work out.” As it turned out, they weren’t vetted, and they couldn’t pay their bills. Huff sighed deeply. “It’s a black eye, I think, for the farming industry in general.”