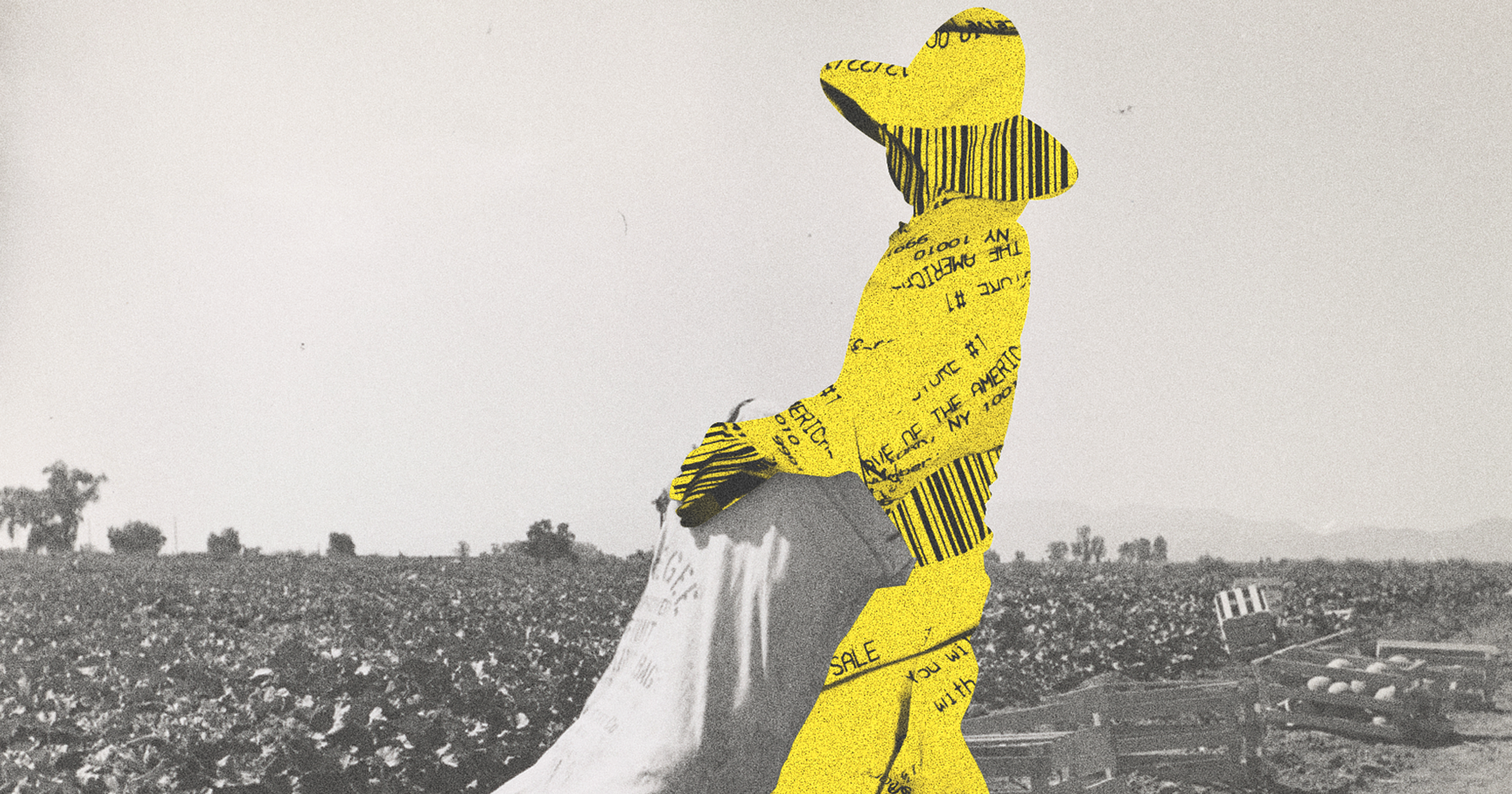

In Florida — the nation’s hottest state — the Senate voted to kill local heat protection ordinances that could save farmworkers’ lives.

It was August 1998 and Letty Pineda felt the beginnings of heat stroke. She was 26 and working in an ornamental plant nursery. She’d emigrated from El Salvador to Boston five years earlier; it was too cold, so she went to Florida. But on that summer day in 1998, the Florida sun — magnified by up to 30 degrees in the greenhouse — got so hot that Pineda lost her breath. She had been cutting ferns for hours straight when a tingling spread through her body. She felt paralyzed, like she could barely move her hands.

“I told my coworkers ‘I don’t feel good, I can’t breathe,’ and they say ‘you’re okay, keep going,’” she recalled. She felt suffocated and panicky. Not long after, she quit.

Today, there are an estimated 2 million outdoor workers in Florida — the hottest state and the nation’s leader in heat injuries. But regardless of the risks, the state has no mandated heat protection policies. On March 6, Florida’s Republican-led Senate passed a bill stripping local governments of their ability to implement their own.

The bill was a partial response to an ordinance proposed in Miami-Dade County, which would have created a “heat standard” for outdoor workers by setting fines for employers who fail to provide water and rest breaks. It would have also mandated that employers post multilingual educational materials related to dangerous heat exposure. But Republican senators argued that municipalities don’t have the authority to instate regulations beyond what’s devised by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which also has no mandatory policies around heat exposure.

Jeannie Economos, long-time coordinator at the Farmworker Association of Florida, has studied the impacts of extreme heat on farmworkers extensively. She was devastated by the Senate vote last week. “Farmworkers doing the work that feeds the rest of us? You can’t even give them information about heat stress?” she said.

The state of Florida has acknowledged the threat of heat exposure in the past, and even took swift action to mandate protections for student athletes after a teenager died in 2017 after a football practice in 90-degree heat. Now, Florida schools must have “cold tubs” filled with ice water available to submerge overheating students. But when it comes to the state’s majority-Hispanic and Black agricultural laborers, Florida has repeatedly failed to respond to the mounting crisis.

Over a decade ago, Economos pioneered a partnership between the Farmworker Association and Emory University in Atlanta to build a body of research on the subject. Of 198 farmworkers enrolled in one study, they found a third experienced “severe” symptoms of heat-related illness like muscle cramps and dizziness, and over half experienced the “moderate” symptom of headaches. In a related study, they found over 80% of workers were dehydrated post-shift, while one-third of them had endured acute kidney injury.

Armed with their research, the Farmworker Association drafted what staffers there refer to as the “good bill,” which offered training on how to prevent heat-related illness and recommended workers have consistent access to water and shade. The bill itself was a compromise, with “no legal component” stipulating when and why growers could be sued, the association’s climate justice organizer Dominique O’Connor said. It was introduced in 2018 and sat untouched for four years, until it was unanimously approved by the Senate Agriculture Committee in 2022. It was then sent to the Health Policy Committee where it was once again ignored.

There’s a culture of fear preventing workers from tending to their own bodily needs, and a lack of accessible information about the dangers and symptoms of heat stress.

This year, the “good bill” was reintroduced and, until last week, finally seemed to be gathering steam, as organizers in Miami-Dade County advocated for their related ordinance. But after what Economos described as industry pushback, the county’s ordinance was stalled and Gov. Ron DeSantis now has the Republican-backed bill waiting for a signature on his desk.

That bill’s supporters, including sponsor Jay Trumbull (R-Panama City), and Ray Royce, executive director of Highlands County Citrus Growers, argue that existing OSHA regulations are enough to hold employers accountable. (Trumbull’s office did not respond to a request for comment.)

“I deal with men and women that are employing frontline workers, and they want those frontline workers to be just as productive and attentive to the task they’ve been assigned as possible,” Royce said in a phone call. Most growers know that “it’s counterproductive to work someone into a state of heat exhaustion,” so the additional guardrails were “overkill.”

In 2021, after a scorching summer that left dozens of outdoor laborers dead nationwide, the Biden Administration announced that it would add protections from extreme heat to OSHA’s agenda. But the regulations still have not been finalized and aren’t expected to take effect for at least another six or seven years. In the meantime, farmworkers in states like Florida and Texas, which recently passed a similar law, continue to get seriously ill and die.

Royce believes allowing individual municipalities to set their own mandates is a slippery slope for employers. “Those things get out of hand, and all of a sudden you’re gonna say now we have a water break and a bathroom break and a voluntary smoking break,” he said. “It gets to where the government is involved in something that goes beyond the safety of the workers.”

Many people may start to experience symptoms in the field, finish up their work day, and go home, where their symptoms progress.

But as Pineda points out, the issue is often systemic. Even if a supervisor doesn’t explicitly deny workers bathroom breaks, rest, or drinking water, there’s a culture of fear preventing workers from tending to their own bodily needs, and a lack of accessible information about the dangers and symptoms of heat stress.

OSHA can levy fines for worker deaths that get reported. But many go unreported in Florida’s agriculture sector, which relies on the cheap labor of undocumented people who make up nearly half of its workforce, and whose fears of deportation and lack of community support systems often render their struggles invisible.

The fines OSHA has doled out in Florida over the last couple years — including $15,000 to an Okeechobee contractor who allowed a 28-year-old visa holder to die from heat exposure in January 2023, on his first day on the job — involve workers who collapsed in the field. But, Pineda says, collapsing in the field is rare. Many people start to experience symptoms in the field, finish up their work day, then go home, where their symptoms progress. Those cases are much less likely to make it to OSHA.

Pineda turns 52 in late March, just before the start of Farmworker Awareness Week, which commemorates Cesar Chavez’s birthday. In the 30 years since she arrived in the U.S., she’s known dozens of people who have gotten seriously ill and experienced kidney failure.

After that terrifying day in 1998, she found work at another nursery nearby, where she could spend part of the day in an air conditioned space. It also came with two 10-minute breaks, plus a lunch break at noon. At the old nursery, it was common to work “all day straight,” with no breaks. There, she remembers her coworkers telling her not to drink too much water because she risked not being hired back if she disappeared to the bathroom too many times.

The new nursery paid $4 per hour, down from her current wage of $4.75. But Pineda had a 3-year-old at home. She felt she needed to take the job at the new nursery, like both their lives depended on it.