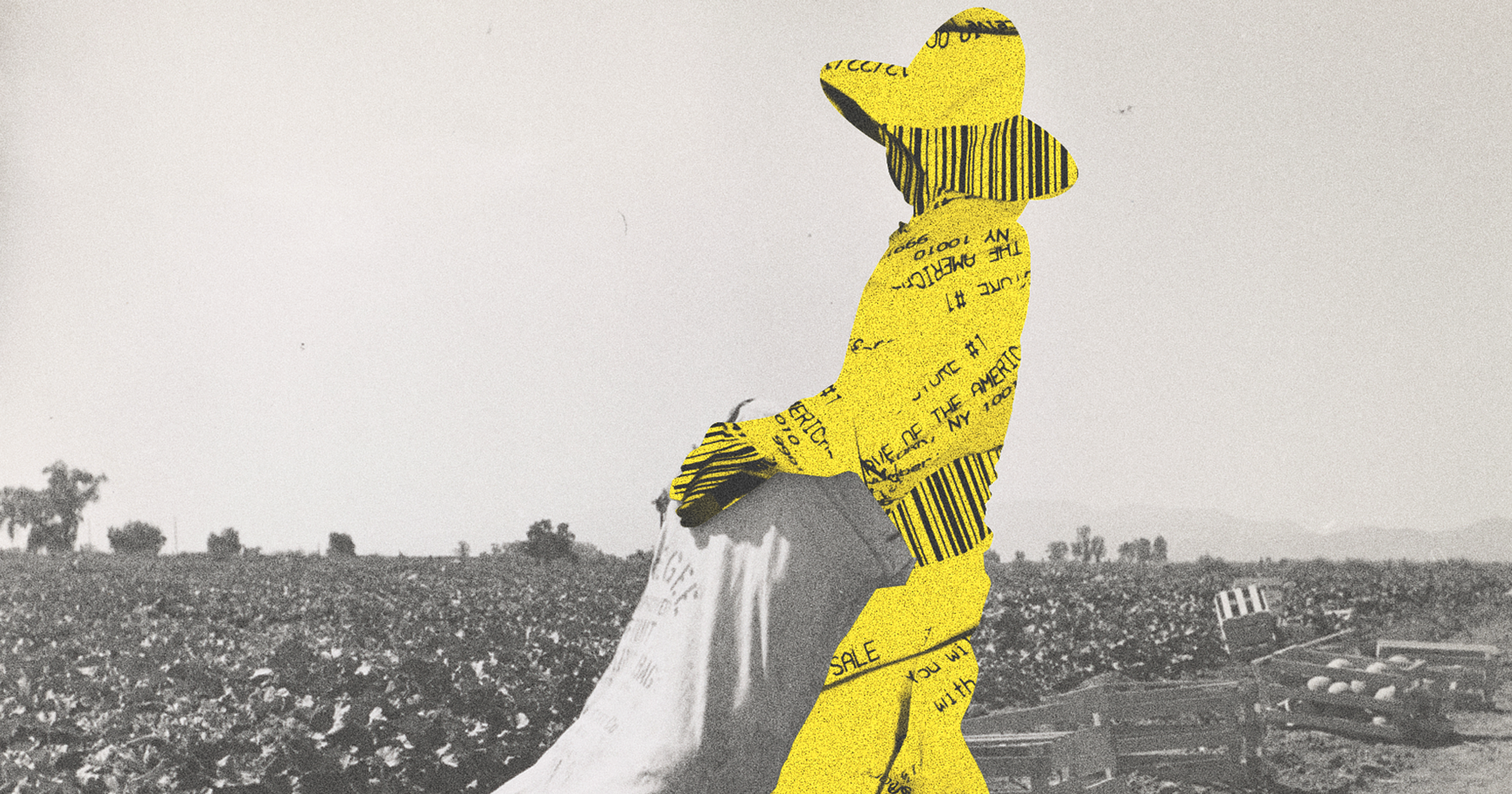

States frame prison agriculture programs as rehabilitative. But a class action lawsuit at Louisiana’s infamous Angola prison shines a light on the inherently punitive nature of incarcerated labor.

When lawyers Lydia Wright and Claude-Michael Comeau were looking into cases of medical abuse at Louisiana’s infamous Angola prison, they started hearing stories about compulsory farmwork.

Through letters and phone calls, the attorneys from the New Orleans-based nonprofit legal center Promise of Justice Initiative heard about prison officials forcing the prison population to work in brutal conditions. For instance, there are times when the workers don’t have access to clean drinking water, they are forced to work even if they are disabled or sick, and they have to work the farms without protective gear. They work with their hands and are denied modern agricultural tools. The lawyers also found workers were routinely denied sunscreen and water, and forced to keep working in the fields even if they needed medicine.

In September of last year, Promise of Justice filed a class action lawsuit against the prison, the state’s corrections department, a for-profit state agency that runs the farm program, and several officials who oversee its implementation. Attention on Angola’s farm line abuse compounded early this year, when the Associated Press published a two-year investigation that tracked prison labor being used to provide massive quantities of food across the nation.

Agriculture in prisons has long been sold as rehabilitative, reconnecting the incarcerated to nature, improving work ethics, and developing skills that could be used after release. But as new programs pop up across the country, academics and legal NGOs are publishing reports of major violations of human rights abuses on prison farms.

Louisiana’s use of farm work in prisons is particularly stark, highlighting how agriculture can be used as punishment and profit in state-run programs. At Angola, for example, the crops grown and harvested by prisoners are later sold on the open market in what the state bills as a positive process of offsetting the cost of incarceration. But according to legal experts and academics that have investigated these types of prison agricultural programs, the problem runs deeper: The labor is inherently punitive rather than beneficial.

Oregon, for example, runs a farm program across 12 facilities since 2014 that its state corrections agency touted in a blog post last year, writing the program “provides educational materials about the art and science of growing and caring for plants to educate and teach sustainable organic gardening practices.” A recent effort in Maine, meanwhile, received attention from a Vice News team for training incarcerated men to cultivate crops and cook in prison. And a Tennessee program received attention from trade publication Farm Flavor, which quoted the guard overseeing the project touting the benefits: “We try to instill a work ethic in the inmates,” manager Doug Griffith told the publication in 2022. “We also want to teach them a skill — whether it’s the greenhousing, operating equipment, or learning how to grow food.”

But researchers like Josh Sbicca of Colorado State’s Prison Agriculture Lab argue that research shows these programs are more connected to slavery than radical, skills-based solutions.

“The rehabilitation pitch is not new,” Sbicca said. “The rehabilitation pitch really begins during the progressive era.”

“If it actually was geared towards rehabilitation, then the incarcerated men would be using agricultural tools to actually cultivate the produce.“

Along with fellow professor Carrie Chennault, Sbicca researches the historical and social context of these types of programs and has published several papers arguing the state is creating a workforce based on discrimination. He is working on a new book looking at how agrarianism gets woven into the prison system and makes the case that in the late 1800s, the presentation of prison-based farm work changed to appease liberal attitudes.

“So this is sort of coming off the heels of the convict leasing system and a lot of the North being really aghast at what was going on in the South and the nationwide turn against what was considered neoslavery institutions,” Sbicca said. “And then this idea that prison could be this reformative, rehabilitative space really kind of comes from a lot of progressive reformers.”

The history of Angola, where the Promise of Justice lawsuit focuses, mirrors this finding. The 18,000-acre property was the site of a large plantation during slavery that was converted first into a convict-leasing operation before becoming a prison in the early 20th century. Now, under the management of Louisiana state-run, for-profit agency Prison Enterprise, the prison grows wheat, corn, soybeans, cotton, and milo. They sell this primarily on the open market, from Angola and other farms they operate across 8 sites in Louisiana.

In terms of rehabilitation, Prison Enterprises’s mission statement specifically features the goal of reducing recidivism and providing work to those incarcerated, stating they prioritize “enabling offenders to increase the potential for successful rehabilitation and reintegration into society.”

Angola’s workers often receive little to no wages. They aren’t eligible for pay in their first three years of working the Farm Line, and only after that they might get paid $0.02 per hour, according to the 2023 complaint. “Louisiana has among the lowest incentive pay rates for incarcerated people working in correctional industries,” it reads.

For Wright, the structure of Louisiana’s system focuses on punishment and profit over teaching any skills.

“The rehabilitation pitch is not new. The rehabilitation pitch really begins during the progressive era.”

“If it actually was geared towards rehabilitation, then the incarcerated men would be using agricultural tools to actually cultivate the produce, they would be consulted about decisions regarding planting crops, what crops to plant and how to harvest them … they would not be sent outside, when the heat index in the Louisiana summer can exceed 130 degrees, without sunscreen or clean water.”

If workers fail to do as they are told on the farm line, they could be put in solitary confinement for an arbitrary amount of time or cut off from communications with their community outside the prison, according to the complaint. Both practices have been documented to harm chances of success upon release, violating Prison Enterprise’s stated mission to build skills for reentry.

“When you dig a little deeper what you get is it’s really a system that’s trying to legitimize itself by using language and tweaking programing to remain in existence, which is not to discount any personal benefits to incarcerated people … being out in a garden is better than being in a cage,” Sbicca said, arguing that states use this clear benefit to frame agricultural work as more positive.

Ken Pastorick, communications director at Louisiana’s Department of Public Safety and Corrections, provided a statement calling the lawsuit “frivolous and entirely without merit.” Noting the prison’s bloody history, the statement argued the state’s efforts have “transformed” farm line programs to become rehabilitative.

“Since the 1980s and 1990s, the Department has transformed the prison by implementing large-scale criminal justice reforms and reinvestment into the creation of rehabilitation, vocational and educational programs designed to help individuals better themselves and successfully return to communities,” Pastorick’s statement read.

Comeau, who investigated Angola’s farm practices alongside Wright, pointed to reports that showed agricultural work neither made money nor prepared those incarcerated for a growing industry.

“We look forward to our day in court.”

“There are jobs where people find ‘Hey, this is a skill I have, I can really take this out of the prison, I can do something with this when I come out,’ and the agriculture job is just not it,” Comeau said. “If you ask people — formerly incarcerated people — they’re not finding that they’re doing farm work outside of Angola. They’re just not, they’re doing other things.”

One state audit from 2019 found that while the program did meet its broad goals of offsetting the cost of incarceration by selling agricultural and material products, the farm line was specifically under-performing. “[N]early 40 percent of the offenders working for PE are serving life sentences,” the audit read. “This means many of the offenders working for PE may not be learning job skills that could help them after they are released.”

For Wright, the state’s framing is a product of its connection to slavery. If the state wanted to rehabilitate its younger population, she argued, they would be sending them to get GEDs instead of working the farm line.

“It’s an institution that’s so deeply rooted in slavery in a place that is so deeply rooted in slavery that the state just doesn’t seem to be able to contemplate moving past it,” Wright said.

Both the state and Promise of Justice Initiative plan to take the case to trial. While motions are still being filed, Wright was direct about her firm’s chances: “We will win,” she said.

Pastorick’s statement also highlighted a desire to sort out the issue via trial: “We look forward to our day in court.”