Chris Smaje believes the breakdown of society is nigh — but farmers may be the key to preserving a livable future.

Chris Smaje is remarkably mild-mannered for a prophet of catastrophe. Once a university-based social scientist, now a self-described “aspiring woodsman, stockman, gardener, and peasant” in rural England, his writing combines an academic’s gentle persuasion with an understated wit that is quintessentially British.

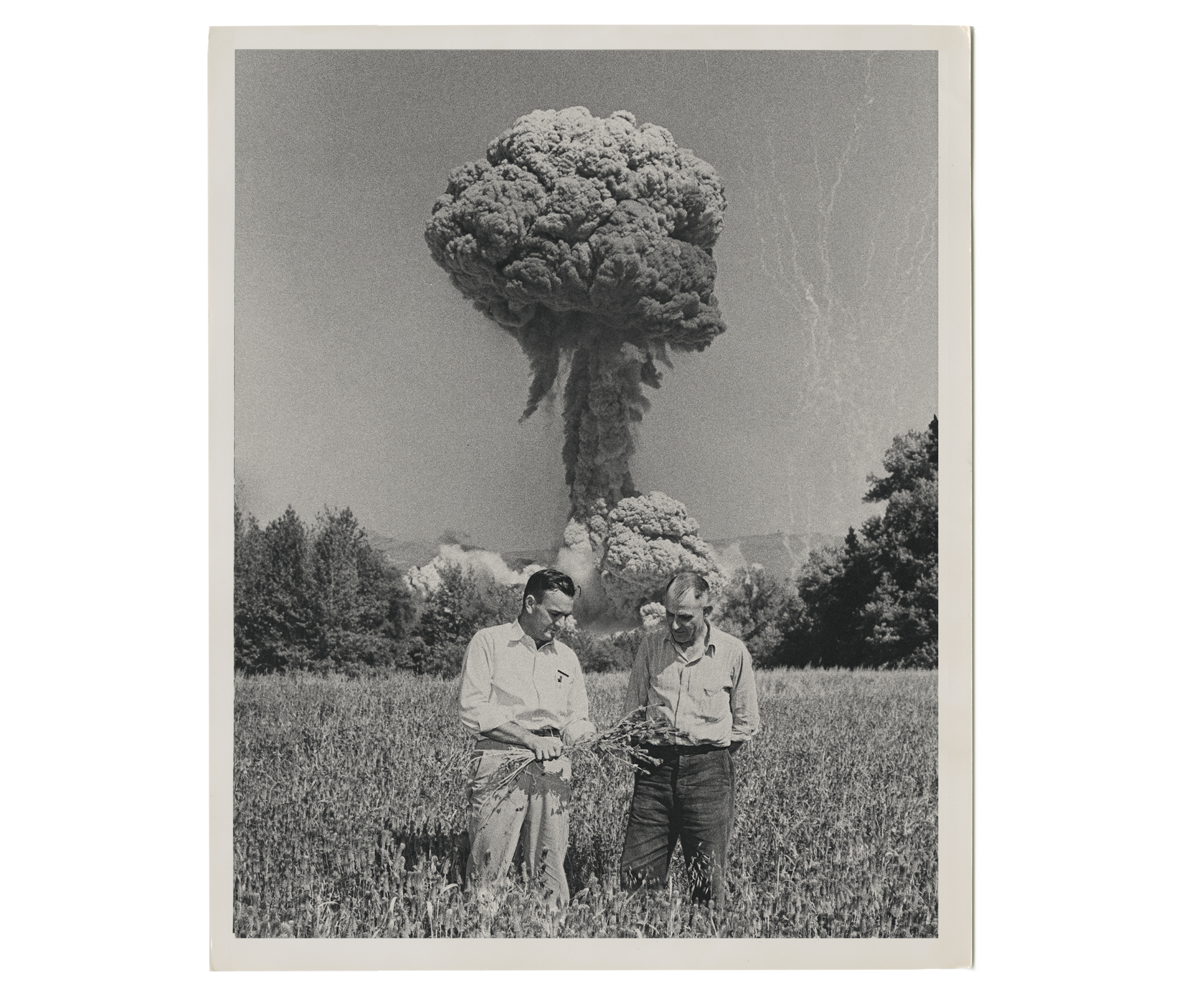

Nonetheless, Smaje speaks doom. His latest work, Finding Lights in a Dark Age: Sharing Land, Work and Craft, does not shy away from proclaiming that the end — at least, the end of modernity as we know it — is nigh. Given the combined pressures of climate change, unsustainable economic systems, and delusional technology worship, he argues, Western civilization is all but certain to face “disorder and uncoordinated breakdown” over the coming decades.

Apocalyptic narratives are not hard to find these days. Less common are visions for what forms of human flourishing might emerge as existing social structures crumble into irrelevance. These are the proverbial “lights” Smaje works to illuminate throughout the book. Offrange readers will be pleased to learn that, by his account, farmers will be vital to keep the hopeful beacons blazing.

When some sort of societal collapse inevitably occurs, Smaje argues, it will likely hit cities the hardest: places that depend on cheap fossil fuels, complex logistics, and orderly government to import raw materials and export waste. As those conditions disappear, urbanites will be pushed to seek refuge in what he calls “open country,” places where it’s feasible to make a living directly from the land.

“Improbable dreams of renewable energy transition, ‘farm-free’ manufactured food and extensive rewilding reflect at best a smugly superior and improbably dematerialized urbanism,” writes Smaje. “Ultimately, there is no better lifehouse than a farm.”

He explores the implications of this big idea in a book that, while difficult to characterize, rarely fails to be lucid and thought-provoking. Smaje roams from imaginary travelogue to personal memoir, philosophical treatise to anthropological field note, in all cases referencing a formidably broad pool of thinkers. His citations include permaculture cofounder David Holmgren, social ecologist Murray Bookchin, Catholic distributist G.K. Chesterton, agrarian luminary Wendell Berry, and Australian Aboriginal scholar Tyson Yunkaporta. Anyone designing a crash course on sustainability thought leaders would be hard-pressed to improve on Smaje’s bibliography.

Farmers tend toward a spiritual worldview, informed by their real experience with the land, that serves as a valuable corrective.

Perhaps it’s best to think of Finding Lights in a Dark Age as a collection of essays, attempts to provide searching inquiry against an uncertain future. Chapters with titles like “Home Economics: Caring” and “Politics of the People” address different dimensions of the post-collapse world, in many cases showing how farmers are most likely to embody the skills and attitudes most needed for the new reality. (Smaje writes less here on the specific types of farming he believes will dominate, but he covers that topic extensively in 2020’s A Small Farm Future.)

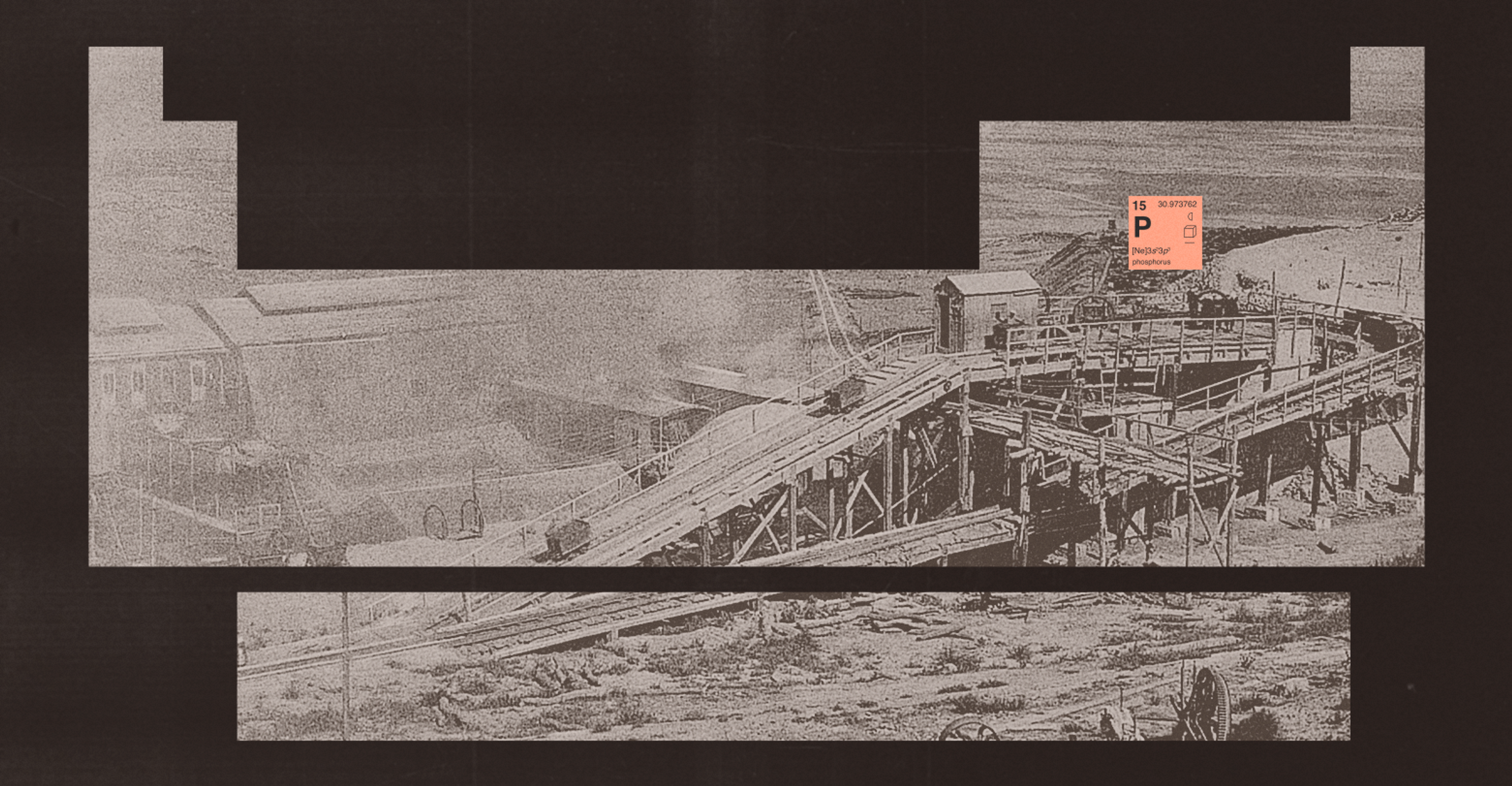

Beyond their practical understanding of land and its potential, Smaje points out, farmers are already used to thinking of the household as a place to meet local needs rather than a mere locus of consumption. They’re familiar with non-monetary ways of organizing labor, like apprenticeships and trading favors among neighbors. And they often have a populist political streak — as explored by Sarah Mock in Offrange’s The Only Thing That Lasts podcast — that seeks to protect local livelihoods against outside interference.

Smaje is clear-eyed about the potential for such interference as society breaks down. Existing governments may scramble to maintain their former glory through authoritarian diktat over rural areas; bands of refugees from failing cities may overrun small communities. Yet he believes there’s room for new, mutually beneficial social arrangements, especially as the loss of cheap energy favors job-rich, small-scale forms of agriculture.

“In all of these scenarios, there’s enormous scope for factionalism, power politics and tyranny,” he writes. “There’s also enormous scope for co-operation, care and benevolence.”

Perhaps most importantly, Smaje argues, farmers tend toward a spiritual worldview, informed by their real experience with the land, that serves as a valuable corrective to modern “Promethean, growth-oriented techno-salvation narratives.” This isn’t necessarily a formal religious faith, but instead an understanding of “immanence,” a sense that the world has its own intrinsic value and inviolable dignity. “The main point of being a pig-keeper isn’t to produce more pork, and the main point of being a person isn’t to get maximum cheapness and convenience,” he offers in pithy summary.

Finding Lights’ final chapter features a vividly imagined pilgrimage out of late-21st-century London by a disaffected laborer to an agrarian outpost in western England. Smaje is careful not to call it a prediction, but instead “a dark thrutopia embodying aspects of arguments made earlier in the book.”

“People used to say ‘this is the twenty-first century’ when they were shocked about bad stuff happening. Now we say it like an amen when it does.”

The big city is beset by malaria and flooding, holding on to scraps of self-importance through policing and land seizures. Regional cities like Bristol have more or less divorced from the national government to run their own local affairs. In the community where the London laborer eventually ends up, the electric grid is a distant memory, sheepskins and apple brandy are more common currency than pounds, and New Age nomads mediate arguments between cattle farmers. It’s a collapsed society, but one where people can still find joy in harvest festivals and the village church. A dark age, with points of light.

This vision felt both plausible and strangely compelling to me — especially as a resident of Asheville, North Carolina, which spent two weeks in 2024 essentially off-grid thanks to the climate-change-enhanced Hurricane Helene. I saw how a community can choose not to devolve into chaos when times get tough; I saw local growers and livestock producers organize to provide water and food to people in need.

The late 21st century feels like a long ways off, but if my four-year-old daughter is lucky, it’ll be within her lifetime. To read Finding Lights gives me some optimism that, in her old age, there will still be a society worth engaging with, growing from the seeds of resilience and realism that farmers are planting today.

Still, I’m haunted by a line Smaje attributes to an old man in his future London. It felt like something on the tip of my tongue, even today: “People used to say ‘this is the twenty-first century’ when they were shocked about bad stuff happening. Now we say it like an amen when it does.”