Many consumers, particularly in the organic market, still hold negative feelings on genetically modified foods. Should these feelings dictate public policy?

Sharp’s at Waterford Farm sits nestled into the lightly sloping hills of western Howard County, Maryland. At 530 acres, the expansive property has grown all manner of fruit, vegetables, and meat animals over the decades. Throughout high school and college, I worked at Sharp’s, starting my days with early morning harvests, driving the farm truck out into the fields just before sunrise, headlights guiding my way through corn stubble and irrigation ponds.

In summer 2008, the Sharps, a multigenerational Howard County farming family known locally for their agricultural expertise and willingness to experiment, planted their sweet corn in two different fields. On one parcel, the farmers grew the crop conventionally, relying on the usual arsenal of synthetic sprays and fertilizers.

The second crop was grown using a GMO seed variety, engineered to express one or more genes from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). With this genetic modification, the corn is made resistant to a range of insects, particularly species of burrowing caterpillars. Sprays with Bt as their active ingredient are commonly used on organic farms. It is by far the main pesticide that I have used over the years, when I’m in a pinch. It’s the pesticide I feel most comfortable using — it targets bad bugs while (mostly) sparing the good ones.

But while Bt is an allowable organic pesticide, Bt corn is not permitted for USDA Organic Certification, which stipulates against the presence of any GMOs on certified farms. Bacillus thuringiensis is found naturally in soil, which allows for its use in organic farming as a pesticide. But once it has been bred into the seed itself using GM technology, it is no longer permitted as an organic input. Once a Bt bacterium has been subjected to the “unnatural” process of transferring its genetic material into a corn seed, it is off-limits for the organic farmer.

The USDA clearly states, “The use of genetic engineering, or genetically modified organisms (GMOs), is prohibited in organic products. This means an organic farmer can’t plant GMO seeds, an organic cow can’t eat GMO alfalfa or corn, and an organic soup producer can’t use any GMO ingredients.”

This commitment to the exclusion of any GMO materials from USDA certified organic operations has been reaffirmed over the years. In both 2016, and again in 2017, the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB), a USDA Federal Advisory Board, voted down the possibility for GM products to be considered for organic approval.

Throughout the 2016 report which preceded the vote, the NOSB makes very stark the wariness both producers and consumers have held for this advanced form of ag tech. The title of the statement, “Report to the USDA Secretary on Progress to Prevent GMO Incursion into Organic,” perfectly captures this circumspection. Indeed, the word “incursion,” meaning “an invasion or attack, especially a sudden or brief one,” appears six times throughout the three-page paper to describe the threat of genetically modified material finding its way into organic systems.

What accounts for this total rejection of GMOs from the world of organics? In an article from 2019, The Cornucopia Institute, a consumer watchdog organization working to ensure “an organic label you can trust,” identified a number of key reasons. To begin with, they point out that “the majority of genetically engineered crops currently on the market have been modified to withstand synthetic pesticides.” It has been estimated that a total 81 percent of GM seeds that are commercially available are engineered for this purpose, and a majority of these seeds are specifically developed to withstand Roundup.

“An organic farmer can’t plant GMO seeds, an organic cow can’t eat GMO alfalfa or corn, and an organic soup producer can’t use any GMO ingredients.”

Notorious for its toxic effects on natural ecosystems and people, glyphosate (branded as Roundup), is synthetically derived, barring it from the USDA’s list of approved inputs on organic farms. It is understandable that with so many GMOs designed to effectively increase the global output of Roundup, organic advocates would be skeptical of the technology as a whole.

That said, not all GM seeds grow into herbicide-resistant plants. One of the most celebrated examples of the application of GMO technology is the papaya. After papaya ringspot virus became endemic to Hawaii, the development of a disease-resistant variety all but saved the industry on the island. Now, the vast majority of papayas grown in Hawaii are genetically modified. In fact, much of the research into new GM crops centers around disease resistance.

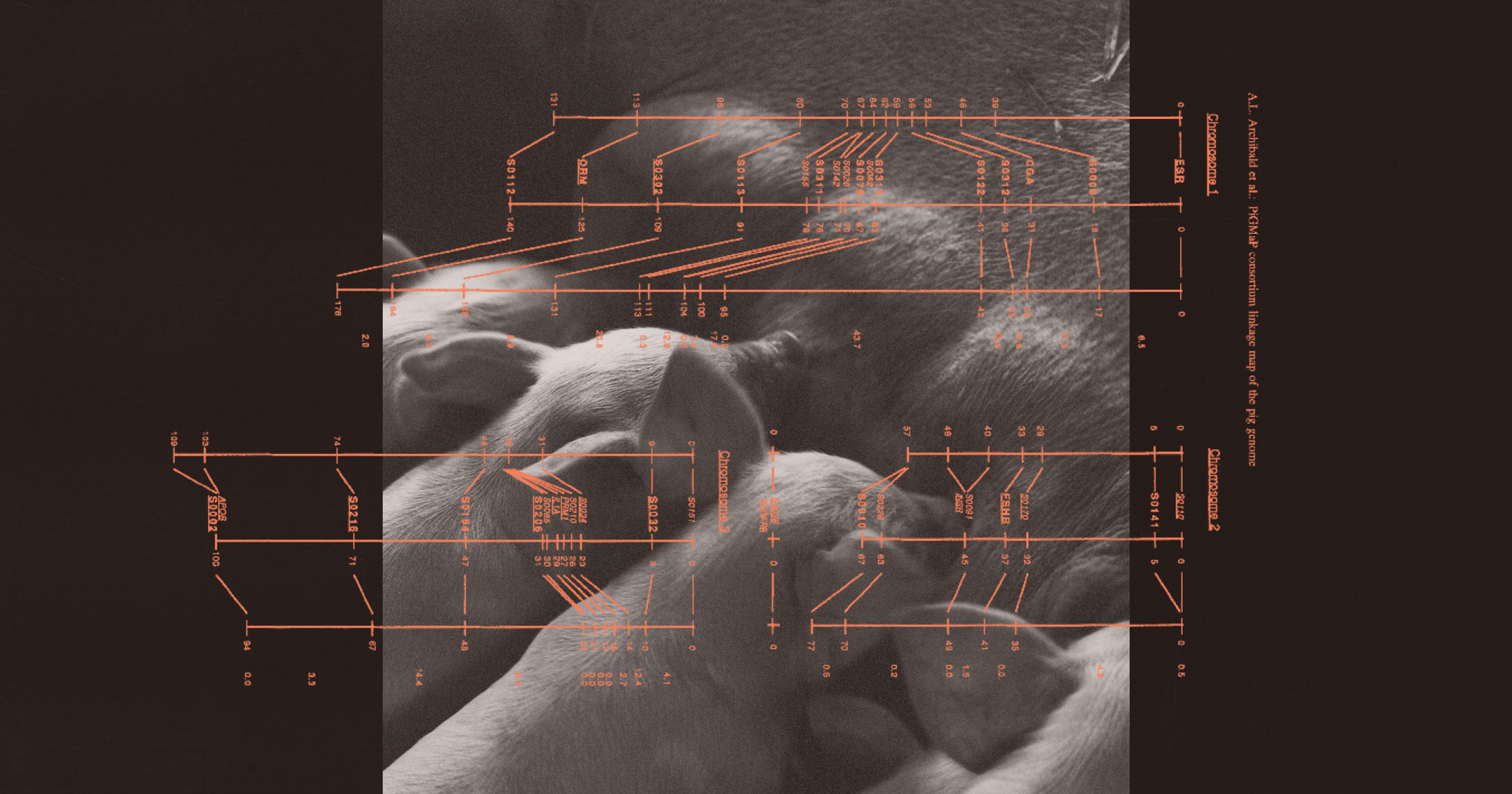

Besides corn, Bacillus thuringiensis’ genetic code has been inserted into a variety of other crops to protect against insects, like cotton, soybeans, and eggplant. The cultivation of these transgenic crops does not result in increased herbicide spraying and has been shown to reduce the overall usage of conventional insecticides.

In July of 2019, Under Secretary of Agriculture Greg Ibach spoke at a House Agriculture Subcommittee hearing to recommend the inclusion of genome-edited crops in organic agriculture. Gene-editing methods represent a newer form of GM. These practices rely less often on the insertion of foreign DNA into genetic code (the “transgenic” method), and more on tools like CRISPR to make changes to the native genetic material of a seed (the “cisgenic” method).

Going up against most organic proponents, Ibach presented his case:

“I think there is the opportunity to open the discussion to consider whether it is appropriate for some of these new technologies that include gene-editing to be eligible to be used to enhance organic production and to have drought and disease-resistant varieties, as well as higher-yield varieties available.”

“There’s a fear, if you bend the rules some, people won’t be willing to pay the premium for organic, which you absolutely need in order to make organic sustainable financially.”

Many of these gene-edited crops make alterations to seed that could be achieved through the organic-approved and time-tested method of selective breeding, albeit much more rapidly. In fact, foods that contain gene-edited crops are not required by law to be labeled as such, unlike the more commonly grown and consumed transgenic GMOs. This is because “current regulations say gene-edited foods are analogous to traditional selective breeding and therefore, do not fall under the same review process as GMOs.”

However, setting aside the ongoing debate around whether gene editing should fall under the category of GMO, the organic industry has so far not shown signs it is willing to consider it as a separate issue. When you buy a product marked USDA Certified Organic, you can be assured that there are no GMOs present, whether transgenic or cisgenic, bred using CRISPR or older technologies.

In 2018, a study by the Hartman Group found that nearly half of Americans would still prefer to steer clear of GMOs in their diets. Interestingly, another study from the prior year showed a wide divergence between public opinion and the scientific community, which largely views GMOs as safe to eat.

With these newer forms of GM crops flying under the radar of regulatory agencies, it is not surprising that many organic champions are not keen on relaxing the rules on GMO, and, in doing so, potentially eroding the trust that consumers give to the label. It is the customer with their purchasing power that ultimately has more say on the matter than the scientist.

The public skepticism of GMOs gets at the core of why we won’t see organic farmers planting Bt eggplant, mosaic virus-resistant zucchini, or gene-edited mushrooms that don’t brown — at least anytime soon. Denise Sharp, one of the head farmers at Waterford Farm (and my first boss), points out that even organic farmers who might be open to growing some GM seeds face pressure from their customer base to keep things the way they are:

They may not put it this way, but many organic consumers are ready to accept their Bacillus thuringiensis on the outside, not the inside.

“There’s a fear, if you bend the rules some, people won’t be willing to pay the premium for organic, which you absolutely need in order to make organic sustainable financially.”

In the 2016 NOSB report, the board states that, “one message has consistently, repeatedly, and abundantly been made clear: consumers across the country have expectations there will be no GMOs in their organic food.” The organization implores the USDA to, “develop policies to address shared responsibilities for GMO contamination.” The board uses the same phrase, “GMO contamination,” in their 2017 follow-up report.

It is clear that the NOSB members see their role, in large part, as defending the public demand. And while that demand might slowly be shifting toward a warmer view of GMOs, a study showed that as recently as 2020, only 26 percent of social media posts surveyed demonstrated explicitly positive attitudes on the matter. It seems likely that this consumer pressure precludes even the possibility for discussion among regulators.

A couple years ago, I worked as a field hand at an organic farm in southeastern Pennsylvania. I remember one morning laying plastic mulch for the spring-planted potatoes. The flimsy and cheap-feeling material stretched across the acres in straight narrow bands. It was bound to end up in a landfill at the end of the season. I had come to understand after untold hours spent cultivating by hand that our use of plastics for weed control was all but necessary to reduce labor and keep us paid a living wage. The head farmer lamented the situation he found himself in. He wasn’t permitted by the USDA certifiers to use the biodegradable plastic. It was made using GMO corn.

Whether or not some GMOs could offer organic farmers another tool, it is apparent that the current paradigm positions these technologies and ecological agriculture as diametrically opposed. The customer is king, and for now, they want to know that when they spend that extra dollar for the certified organic sweet corn, they are nowhere near a GMO. They may not put it this way, but many organic consumers are ready to accept their Bacillus thuringiensis on the outside, not the inside.