Over a decade after the maple syrup grading change, Grade A Dark is just not the same.

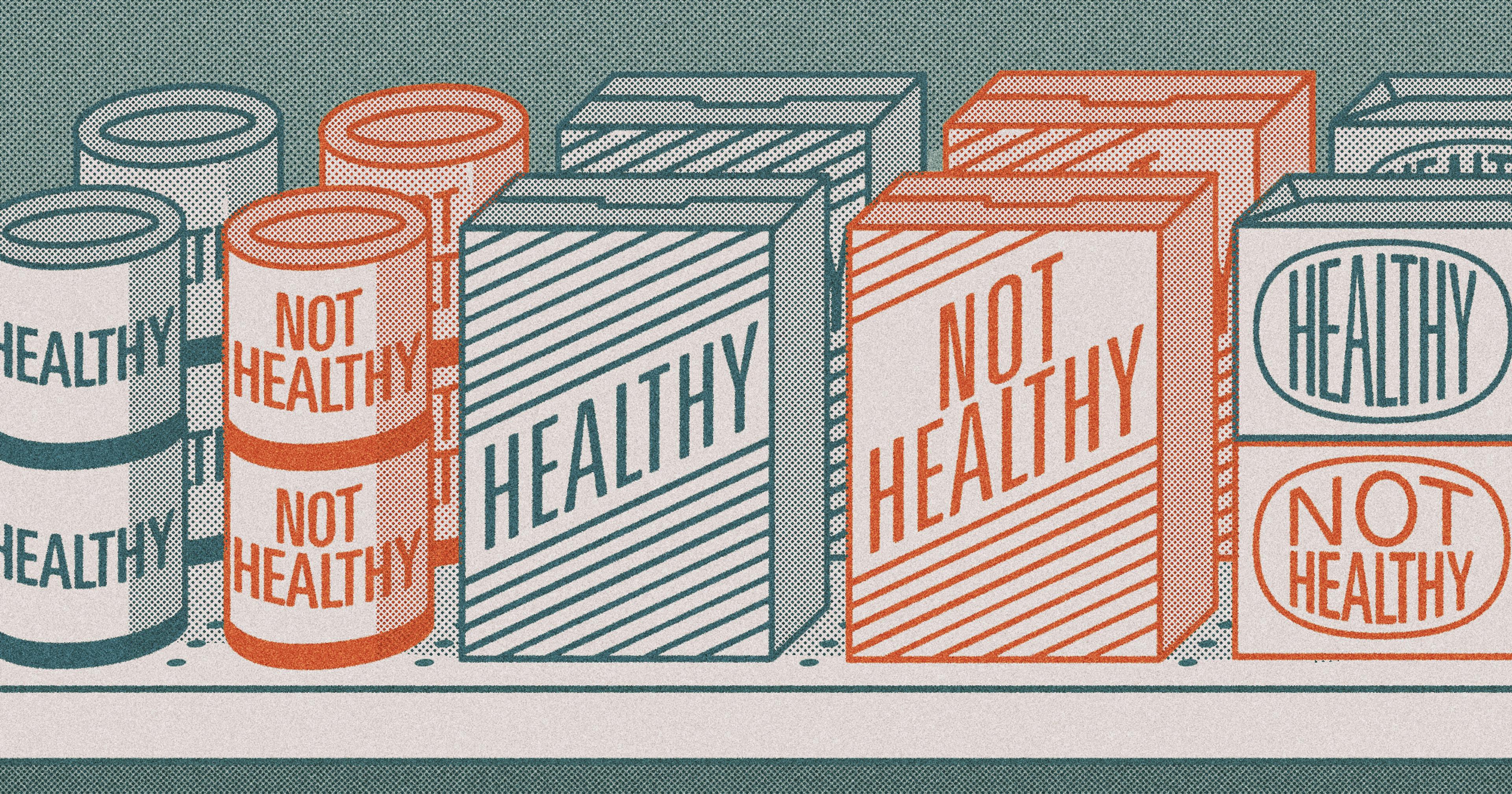

The maple syrup industry was trying to make things easier, really they were. After all, the world of food labeling is a quagmire — it is the rare consumer who has really studied the difference between “cage-free” and “pasture-raised” eggs, who understands what separates “natural” from “artificial” flavors.

But somehow, maple syrup was even more complicated, with labels differing between not just countries, but individual states. (Vermont has a team of state inspectors to enforce its grading system.) In any store or sugarhouse, you could find things like Grade A Fancy, Grade A Amber, or Grade B. But a bottle of “Grade A Medium Amber” in Vermont was the same product as “No. 1 Light” in Canada.

How did that make any sense?

These labels, regulated either by the USDA, Canadian law, or state requirements, were all meant to convey the color and flavor of the syrups. For example, Grade A Light Amber was thinner and clearer; Grade B was dark and intense. But in Canada, which used a numerical system, No. 1 could range from light to medium, while a darker No. 2 could also be named “Ontario Amber” in some places. The same product could be labeled “Grade A Light Amber” if produced in Maine, and “Vermont Fancy” in Vermont.

So the maple syrup industry — specifically the International Maple Syrup Institute (IMSI), a trade group representing the industry in both the U.S. and Canada — proposed a solution, and released a new plan in 2011. Gone would be Canadian No. 1 and No. 2, and Grade A and Grade B in the U.S. Instead, all manufacturers would label their syrups “Grade A,” and specify the color and taste as ranging from “Golden Color With Delicate Taste” to “Very Dark Color With Strong Taste.” This way, in theory, customers could choose maple syrup based on whether they wanted something lighter or more robust, rather than the perceived quality — the assumption being that no one would buy Grade B if a Grade A were available.

Of course, some customers never needed convincing. I grew up in a Grade B maple syrup household, which was essentially maple syrup for Real Heads. It was the most maple syrupy syrup you could get, viscous like toffee, like licking a sweet tree. Knowing Grade B was a good product made you feel like you were in on something. There was a punk edge to buying it, publicly declaring your love for something that sounded worse in comparison to its counterparts, but that you knew was better. Amateurs could have their Fancy Grade As — basically sugar water — in a novelty maple leaf-shaped bottle. The real ones, who understood pancakes were only a vehicle for the good stuff, knew Grade B.

The new grading system was accepted, and has been in place since 2015. At any grocery store or farmer’s market, you’ll find a range of Grade A jugs of maple syrup, the only difference being an adjective to tell you whether you’re getting a lighter or darker product. But despite it being over a decade since the change, some consumers are still not over it.

The maple syrup industry insists Grade B has just been replaced with Grade A Dark or Very Dark, that the same great product is there under a different name. In fact, they were trying to save Grade B when they made the change. “There are many consumers who prefer good quality Grade B or Canada No. 2 Amber or even darker coloured syrup. The new system would place all colours of maple syrup on equal footing in the retail market, provided they meet taste and quality standards,” wrote the IMSI in its 2011 regulatory proposal.

In theory, the change could even help more customers discover the benefits of darker syrup. “Some dark syrup with bold flavor had been labeled as Grade B for reprocessing and not intended for retail sale. But, the USDA said there’s more demand for dark syrup for cooking and table use,” wrote Today at the time of the change. Instead of seeing “Grade B” and thinking it was an inferior product, renaming it “Grade A Dark” would hopefully get more customers to buy it.

Grade B was the most maple syrupy syrup you could get, viscous like toffee, like licking a sweet tree.

Pam and Rich Green of Green’s Sugarhouse in Poultney, Vermont, have seen the positive impact of the labeling changes in the past decade. “People would pick up ‘Fancy’ thinking it was the best, and then they didn’t like it because it had a very delicate flavor,” said Rich Green of the old labeling. Now the labels are more tied to the flavor you get in the bottle, so “if they like dark roast coffee or dark chocolate, then maybe they’ll like dark robust.”

Having them all labeled Grade A, they argue, is just assuring the customer that they are getting the same quality regardless of color. Plus it sounds better. “You wouldn’t buy grade B eggs or grade B meat,” said Pam. (Grade B eggs do exist, but are typically not sold in grocery stores).

But some fans of Grade B say they never equated the name with quality. “I liked that intensity just for regular use. I felt like I was getting more of the tree,” said Michael Metivier, who started buying Grade B in the Berkshires when he and his wife lived in Western Massachusetts. And the new naming system, for him, presents as many problems as the old one. “Having a range of Grade As with different labels seems unwieldy while Grade B felt pretty clear … It felt more like ‘This is the serious stuff.’”

This would all be easy enough to navigate if consumers knew they were getting the same product under a different name. But some consumers say it’s still not the same. “The commercial Grade As that I’ve tried that are supposed to be the most like Grade B still look too light to my eye and taste a little thinner, less interesting somehow,” said Erin Keane, who started seeking out Grade B syrup after attending a maple syrup festival in Indiana about 15 years ago. She’s mostly chalked it up to memory clouding her experience, but she very well could be right.

“People would pick up ‘Fancy’ thinking it was the best, and then they didn’t like it because it had a very delicate flavor.”

The change in labeling also came with a change in which syrup goes into which category. To be legally categorized as maple syrup (as opposed to a “pancake syrup” or other maple imitator), the product must be produced by the concentration of maple sap, and have soluble solids (mainly sugar) between 66% and 68.9%. The different grades are then judged by light transmittance, or how transparent it is.

Producers sometimes advertise that Grade A Very Dark used to be called Grade B, but that’s not entirely true. What was sold as Grade B in Vermont and Ohio, or Canada No 2. Amber, had to have 27-43.9% light transmittance, while anything below 27% was sold as “Commercial Grade” or “No. 3.” But the change in naming also came with a change in light transmittance classification. Now, Grade A Dark is a wider range of 25-49.9% light transmittance, while Grade A Very Dark is anything below 25%. It seems minor, but now that means it’s possible to buy a Grade A Dark syrup that is lighter than what Grade B used to be.

It also could be possible to buy Grade A Very Dark that is darker than formerly Grade B syrups, but in all likelihood that’s not happening. According to Tasting Table, Grade A Amber is the most popular, and a quick scan of a few local grocery store shelves confirmed that even when there were a range of maple syrup brands, Grade A Amber was by far the most common grade available. And a look around at individual producers show some don’t even make Grade A Very Dark. Like any other business, maple syrup sales work by supply and demand.

Both Kaylie Stuckey, executive director of IMSI, and Peter Christopher, IMSI’s vice president, agree that while there are no official statistics, Grade A Amber is the crowd pleaser. This makes an intuitive sense — it’s not too dark and not too light, suitable for both baking and drizzling on waffles, the kind of syrup most people would be happy enough with. If you’re stocking shelves for the general public, it’s what will sell.

It’s also the easiest to stock because that’s what maple syrup producers make the most of. Golden Delicate syrup is produced at the very beginning of the season, while Very Dark syrup is produced right at the end, so less of each is made. “I have to have enough volume on the shelf to put out a product,” said Christopher, who is also the plant manager at Maple Grove Farms of Vermont. So Amber and Dark go out for mass consumption, while the rest is usually bottled and sold at sugaring houses.

What I and other Grade B fans want is credit for knowing the band before they got big, as it were.

There is an inherent tension in trying to label and classify a natural product. Just as the same wine will taste different year over year, maple syrup changes with the seasons, with the soil, and across geographical zones — even if it carries the same name. This was the case then and now, whether it was called Grade B or Grade A Very Dark. But those who miss Grade B don’t necessarily miss a specific product, but a phrase that symbolized they were different, an identity that made them unique from other consumers.

But perhaps they’re not so unique anymore. It’s clear the Dark and Very Dark syrups are enjoyed by those who try them — some producers are saying they’re becoming more popular, and perhaps some of that is indeed because of the naming change. “If you don’t know maple syrup, I think you’re automatically drawn to the lighter colors, but then I find once you actually get to know syrup and you taste enough of it, you’ll find that the darker flavors are more robust,” said Stuckey. It’s just that because of the quirks of maple syrup production, you have to be the kind of maple syrup fan who actively seeks them out, rather than casually picks up whatever’s in the syrup aisle.

This whole grading change was an exercise in public education, to convert casual grocery shoppers into the kind of people who know more and seek out exactly what they want. Which is precisely what chafes. That the same syrup can be bought and enjoyed is not the point (though let’s be honest, everything being called “Grade A” is kind of silly).

What I and other Grade B fans want is credit for knowing the band before they got big, as it were. For seeing the value in Grade B before it got a makeover to appeal to the people who previously never gave it a chance. Then again, regardless of the name, you still have to know where to look for it. Nothing feels more punk than that.