Producers ditch certification despite rising organic sales to maintain more sustainable practices.

Seventeen years ago, Jennie and Hans Schmidt tried something new on their 2,000 acre family farm in eastern Maryland. Designating a 100-acre section for organic crops, the couple spent four years transitioning the land to earn the USDA’s certified organic designation on the grains growing from it. Such a transition requires farmers to comply with a long list of USDA regulations, conceived to ensure that crops certified as ‘organic’ result from “an ecological production management system that promotes and enhances biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity.”

But after seven years of organic farming on those 100 acres — four years to make the transition, followed by three years producing certified organic corn — the Schmidts found the organic farming hadn’t paid off. They decertified the organic portion of the farm and replanted Bt corn, a genetically modified crop. Their story highlights the challenges some farmers face when attempting to meet organic certification standards while still profiting from and caring for their local environment.

“It was an economic decision,” notes Jennie, referring to both the creation and demise of the organic section of the farm. “The yields were down, and if your overall yield is so reduced compared with biotech corn, it’s an overall loss.”

Hans Schmidt serves as Maryland’s Assistant Secretary of Agriculture for Resource Conservation, making the Schmidts especially attuned to sustainability concerns on their farm. But their difficult experience with organic agriculture is not unusual among farmers. Surveys from the past two decades suggest that a substantial number of farmers move away from organic agriculture after becoming certified, despite consumer demand for organic food steadily driving up organic production. In 2012 survey data from sixteen states, 36% of 234 farms reporting organic status had been organic, but then had dropped certification. In 2008, a UC Davis study reported that 20% of California organic farmers had dropped organic between 2003 and 2005.

In the American regulatory system, GM or transgenic crops and organic certification are mutually exclusive: a farm or farm section can grow genetically modified crops or be organic certified, but not both. Farmers interested in organic techniques are therefore often hamstrung, as studies suggest organic farming produces lower yields compared with conventional agriculture. Farmers must balance the benefits of genetically modified crops against the premium price attached to crops bearing the organic certification.

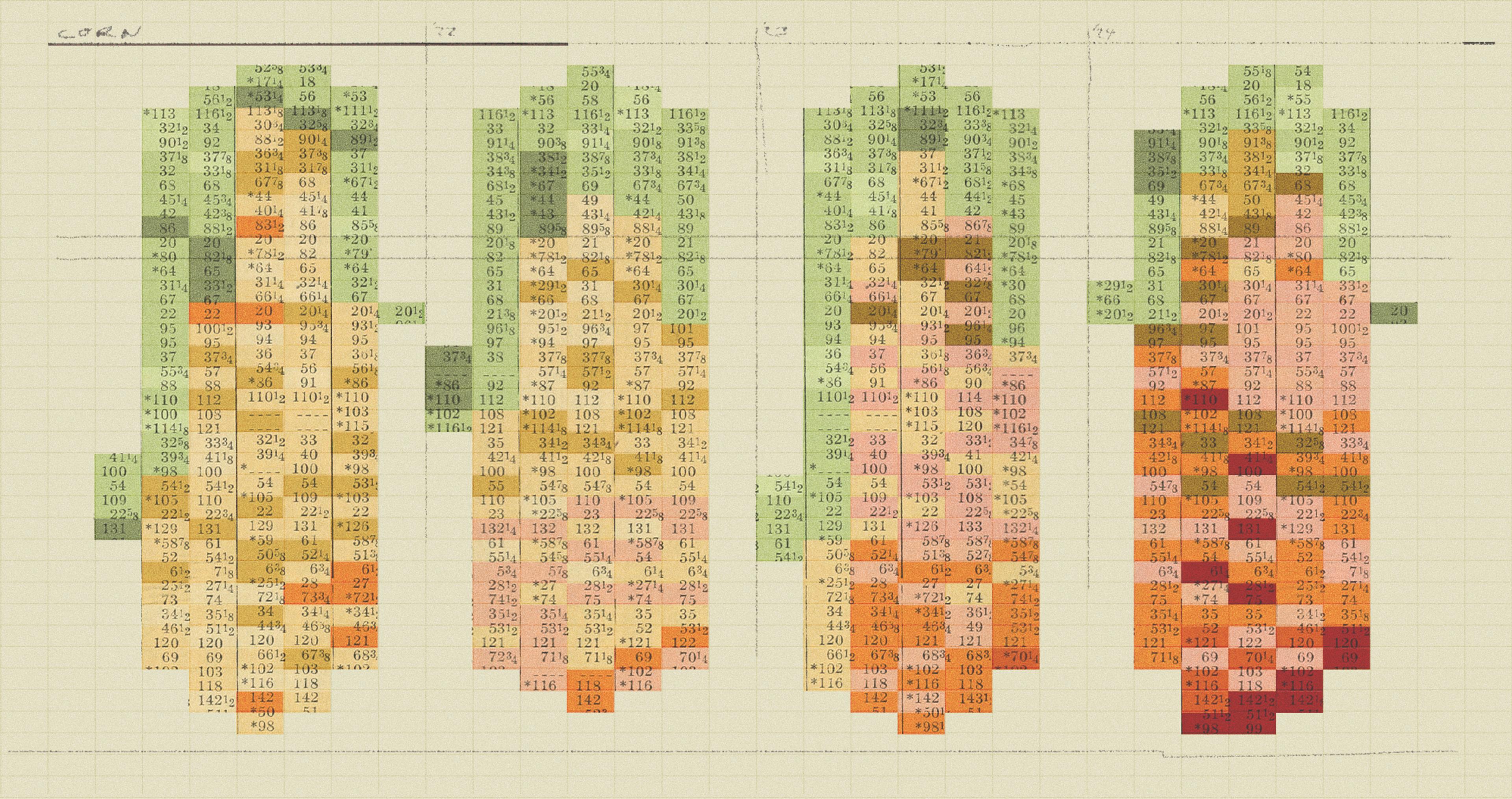

The financial decision to transition to organic farming is characterized by a series of tradeoffs. Broadly speaking, organic products require fewer inputs, exhibit lower yields, and command higher prices than their conventional counterparts, and it is therefore common to make a holistic comparison on the basis of net return per acre planted. Examining this metric across farms in the US, the Center for Commercial Agriculture at Purdue found that organic corn producers received a greater net return per acre than conventional producers on average, but the magnitude of the improved return varied greatly by the sophistication of the farming operation. The top performing decile of organic corn growers achieved almost five times the return of their conventional counterparts, whereas the lowest performing decile of organic corn growers on average achieved only double their conventional neighbors’ return.

Some studies suggest that GM crops may make agriculture more sustainable by reducing use of land and consumables as well as production of greenhouse gases. A recent German analysis of agricultural data claims the European Union could decrease its agricultural greenhouse gas emissions 7.5% by expanding the use of GM crops and. The researchers calculate that a shift to more GM crops would prevent the release of 33 million tons of CO₂-equivalent gases, largely by avoiding the development of more land for farming.

The Schmidts encountered other sustainability challenges in their organic transition. Their farm sits on Maryland’s Delmarva peninsula, where coastal soils are loose and vulnerable to erosion. As a result, the Schmidts have historically practiced no-till farming, which releases less carbon from the ground than tilling methods. The Schmidts crimp the cover crop down to form a thick mat of residue on the soil surface in hopes of suppressing weeds. But practicing no-till while attempting to keep the organic certification proved difficult, as weeds outcompeted the crop. The Schmidts eventually switched to tilling their organic land, which exacerbated soil erosion. The Schmidts would have preferred to maintain an organic certification without tilling, but most herbicides don’t qualify as organic. Compared to their non-organic colleagues, organic farmers can avail themselves of far fewer herbicide options. “The biggest drawback to organic farming for us was the damage that tillage does to the soil,” says Jennie. “If no-till organic production had been successful, I think we’d have kept that farm in organic production.”

To protect their organic corn, the Schmidts sprayed it once or twice per year with Dipel, an organic insecticide made of the bacterial species Bacillus thuringiensis. The bacteria produce Bt protein, which kills the corn earworm. Bt is harmless to mammals, including humans, because we lack a receptor present in the insect worm’s digestive tract. In contrast, the Schmidts’ GMO corn, known as Bt corn, is genetically engineered with the Bt gene. It produces its own internal Bt in amounts large enough to kill the earworm, and is a more successful pest-killer than spraying organic corn externally. Since Bt corn is a transgenic crop, however, it’s a disqualifier for organic certification.

Since switching back to Bt corn, the Schmidts have resumed no-till farming.

Demand for organic products will likely continue to rise. It remains to be seen whether family farmers like the Schmidts will be able to benefit from that demand.