Built on years of research, the federal agency’s new tool aims to help farmers reduce heat stress in the world’s most widely consumed animal.

Any experienced swine farmer knows this, but maybe you don’t: When pigs roll around in the mud, it’s not because they are filthy, uncouth beasts. Rather, they are large and prone to overheating, without the evolutionary benefit of sweat glands. Mud gives them an ad hoc cooldown, like a bird splashing in a puddle.

“Think about a human’s behavior response to heat — you’ll probably try to go inside an air conditioned building,” said Jay Johnson, an animal scientist who leads USDA’s Livestock Behavior Research Unit in West Lafayette, Indiana. “Pigs use what they have available, so that’s why you’ll see them wallowing in mud or some other water source.”

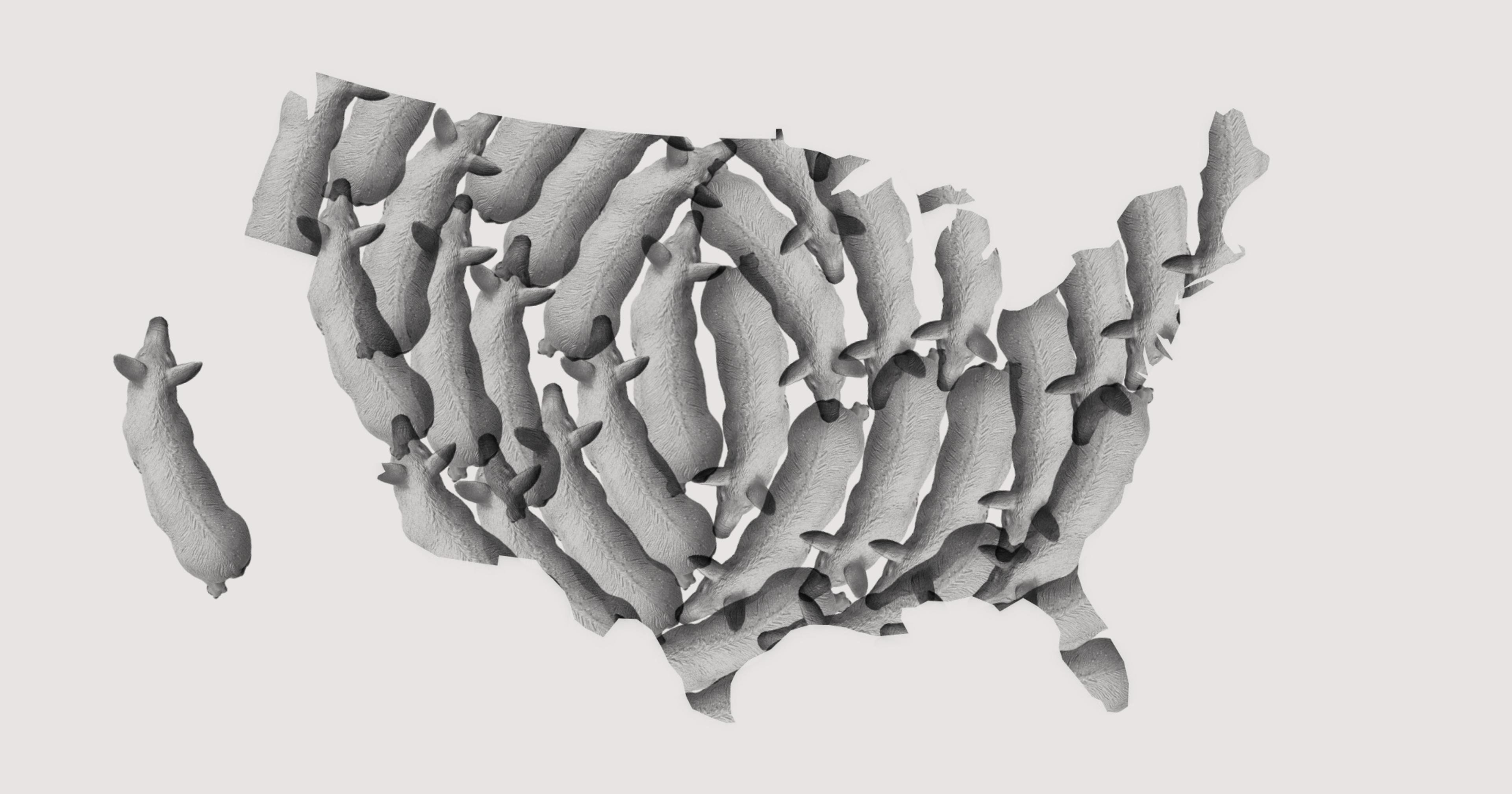

But a natural cooldown is not always available, or sufficient, for overheating hogs. These animals are particularly ill-suited to coping with extreme heat, a concern producers have grappled with for years: USDA researchers estimate that heat stress costs American pork producers nearly a half billion dollars per year.

Farmers were so persistent and vocal about their concerns, they eventually prompted USDA to create HotHog, a cheekily named phone app to help detect when your pigs are overheating.

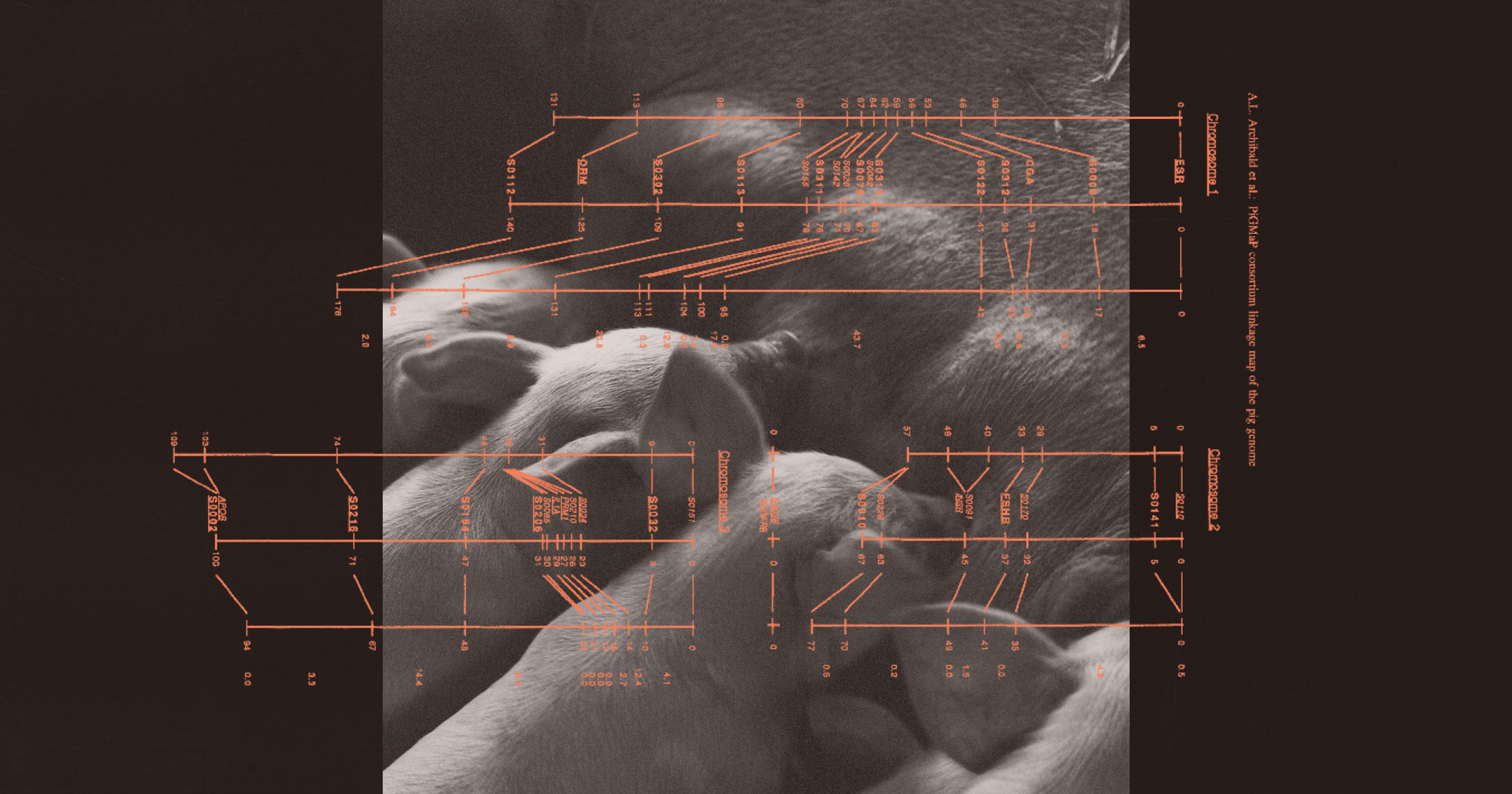

HotHog was released this summer, but its history goes back to 2017. Johnson and an interdisciplinary team of government and academic researchers set out to create a state-of-the-art tool to specifically address heat stress in pigs. Johnson’s team looked at breeding sows, as heat is known to have particularly negative effects on reproduction in pigs and other livestock. Pigs have a different range of temperature needs and preferences from other mammals, though (see: cows), so the HotHog research focused on pinpointing exactly what the thermal indices are.

According to Lindsey Robbins, senior animal care analyst at the Department of Homeland Security, this project was one of the first to test sows’ behavioral preferences for different temperatures, not just physiological. In other words, they observed how much heat a pig likes. It’s like pig farmer Phil Borgic told Illinois Public Media in 2021: “Pigs can’t talk to us, but we can listen to them, and we can do that by … observing their habits.”

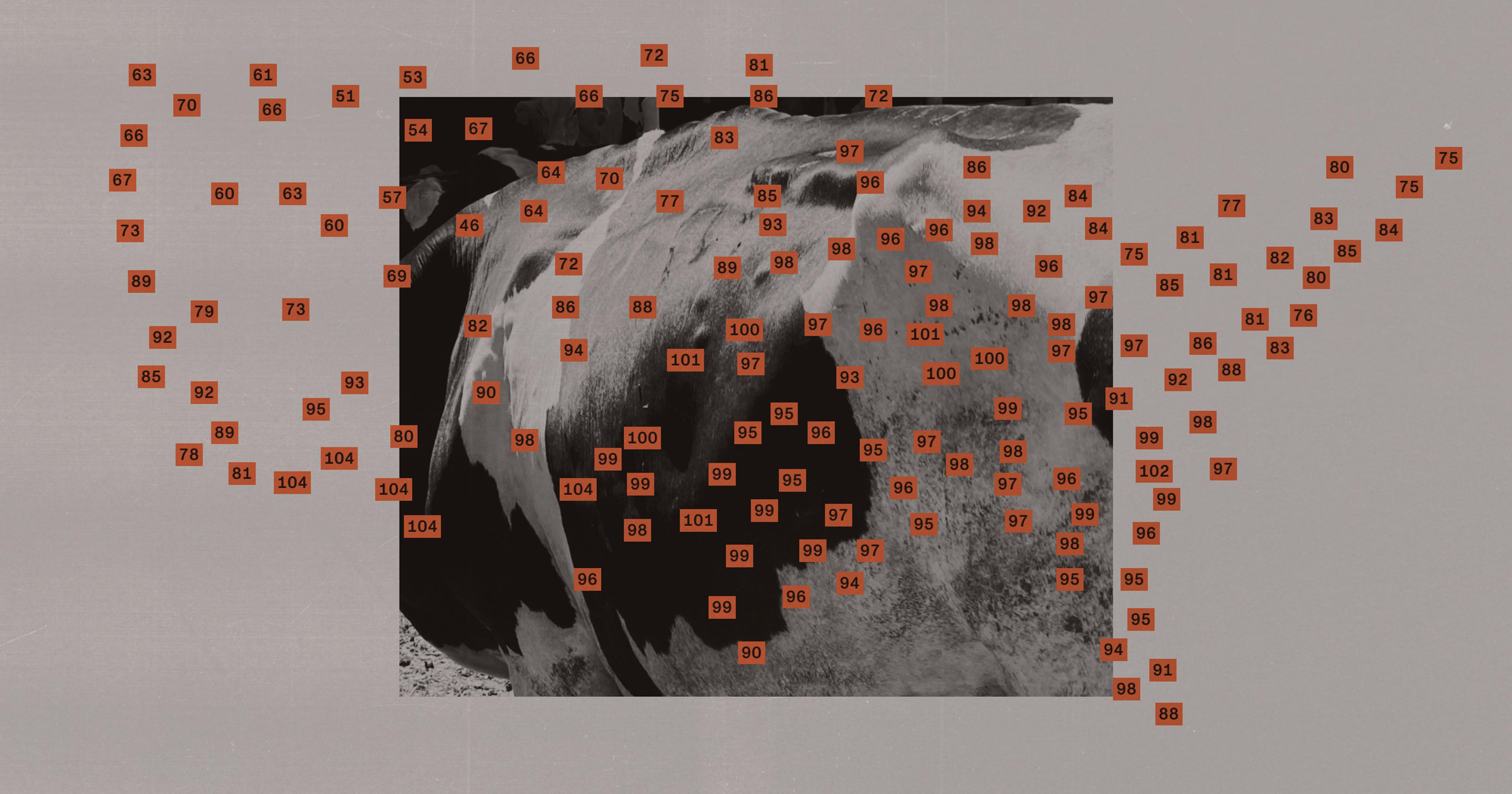

Robbins’ team helped construct a 40-foot-long, six-foot-high containment facility, heated differently throughout. Then they simply observed sow behavior within the structure: which parts the animals preferred, which they avoided, and whether their behavior shifted during different activities like feeding. Robbins, who was at Purdue University when the study was conducted, said there was little precedent to this work.

“Usually, instead of asking sows what temperature they prefer, they tend to estimate it based on backfat ratios, based on size, and based on old research,” she said. “So a lot of the research that does exist ... was done in the 1950s.” Robbins added that pig genetics have changed quite a bit since then.

““This is a production issue, but it’s also just an animal welfare issue.”

Robbins said her portion of the project was kind of a “stepping stone” to learning about heat stress, simply determining preferences before a pig reaches extreme conditions. Allan Schinkel, an animal sciences professor at Purdue who also worked on HotHog, said his research looked at pigs’ physiological responses to heat. Namely, he helped find the “break point,” when their labored breathing gave preliminary indications of heat stress. Precision was key.

Schinkel said heat stress causes an array of detrimental effects that both make life unpleasant for the pigs and lose money for their owners. For instance, it reduces its feed intake, leading to reduced, slower growth, and eventually leading to lower profits for producers (something pig farmer Borgic also noted). “This is a production issue, but it’s also just an animal welfare issue,” said Schinkel.

The HotHog app is tied in to a user’s local weather, and gives six simple, color-coded categories for how your pigs are probably feeling: cool, comfortable, warm, mild heat stress, moderate heat stress, and severe heat stress. You can then check on the behavioral and physiological signs a sow typically exhibits in different temperatures, and learn about various mitigation strategies. Ventilation, fans, sprinklers, and cool drinking water are among the more basic suggestions, while long-term strategies may include costly equipment upgrades.

Johnson said HotHog is very much a work in progress; they intend to release versions that focus on boars and infant pigs, as well as a Spanish-language version coming soon. As to why the staid USDA went for such a lighthearted app name? (Another USDA app is called the “Land Potential Knowledge System,” for instance.) “At first we thought of some of the more, I don’t know, rigid names for this kind of thing,” said Johnson. “Then I was driving to work one day and it hit me: HotHogs! What a great way to catch people’s eye, let them know this isn’t just a run-of-the-mill app.”