Federal officials have been running simulated emergencies to help prevent a wild pig pandemic, part of a wide-reaching initiative to protect the country from African Swine Fever.

Last October, experts and stakeholders from across the Northwest gathered in Spokane, Washington, to discuss a pressing issue of national security. They ran simulations, teased out scenarios: How would they coordinate between various state and federal agencies and tribal populations in the event of a potential threat? For two days, groups discussed the ins and outs of this critical issue inside the convention center, in what’s known in emergency management circles as a tabletop exercise.

On the agenda: emerging pig diseases like African Swine Fever (ASF), and the potential for feral hogs to help spread them.

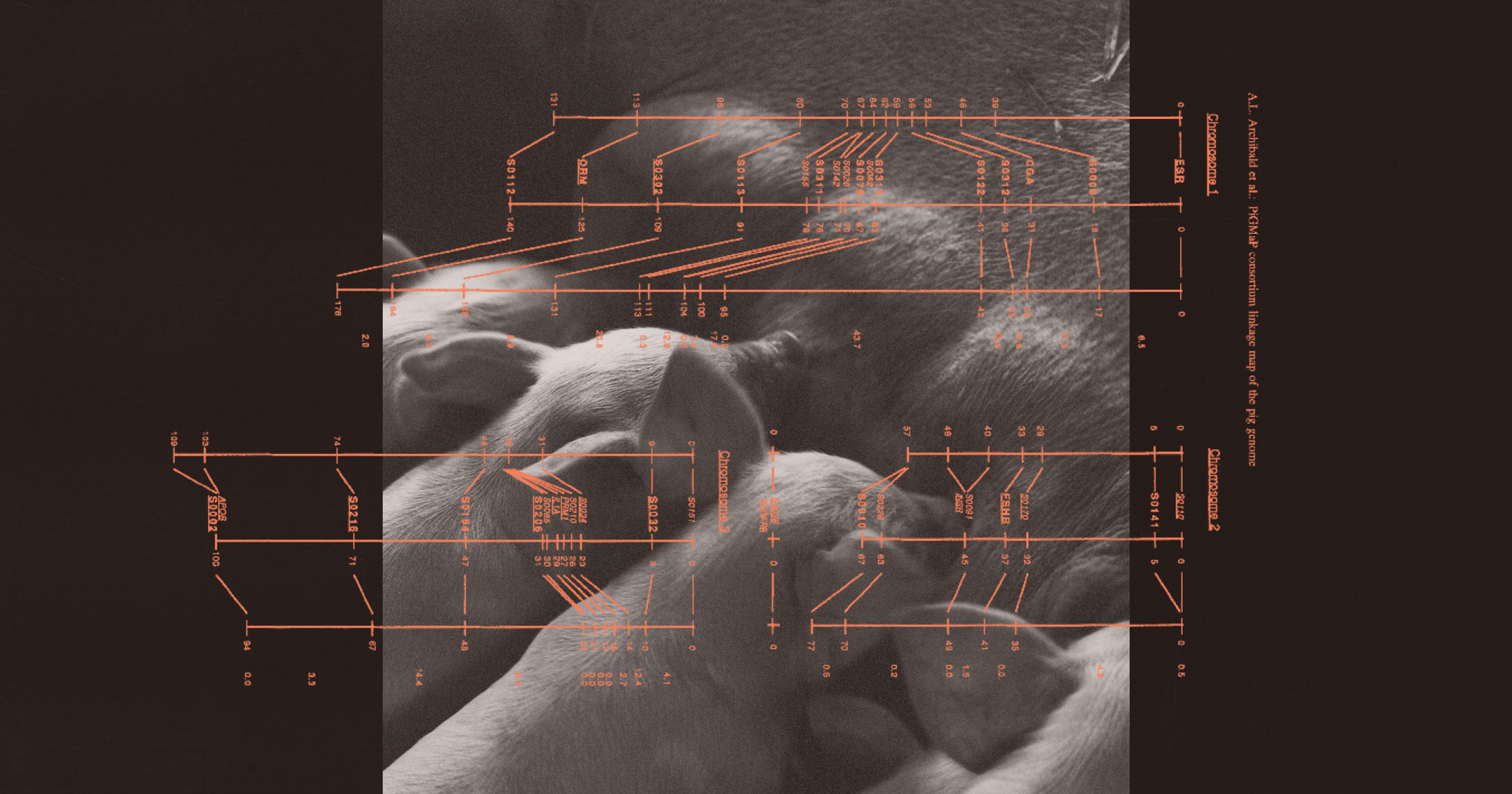

Feral swine are a notoriously damaging invasive species that can quickly impact agricultural facilities and products. They hunt small animals that live or nest on the ground, threatening endangered or threatened species. They compete for resources like food, water, and habitat, displacing resident creatures. They’re “ecosystem engineers,” changing the environment around them by degrading water quality and wetlands, and altering plant makeup in an area. They’re known to “strip a field of crops in one night,” among other threats.

“It’s remarkable how destructive they are,” said Vienna Brown, a biologist with the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). “In many ways, they’re just this unstoppable creature that is, from a human perspective, the worst-case scenario of swine.”

But all this destruction pales in comparison to a quick-spreading and deadly pig pandemic. The tabletop exercise in Spokane was concerned about pigs as a viral vector, potential carriers for disease that obey no laws of humanity — whether property lines, state lines, or international borders. Wild pigs are known to transmit parasites and diseases like pseudorabies, brucellosis, and tuberculosis. But most troubling in recent years is African Swine Fever (ASF).

ASF, which kills close to 100% of infected pigs, is a growing problem globally. It’s endemic in parts of Africa, and has spread rapidly in Europe and Asia. It’s never been detected in the United States, but spread since 2018 has heightened concerns, when it jumped from Eastern Europe and Africa to Belgium before rampaging through Southeast Asia, according to Brown.

It’s important to note: ASF cannot currenly be transmitted from pigs to humans. But it’s one of the top threats to U.S. pork production, which exported $7.7 billion of product in 2022.

Eleven European Union countries have documented ASF in wild boars as of a 2023 report, and researchers have warned the animals can serve as a reservoir that can spill over into domesticated herds. This makes feral pigs not just a damage concern, but a food security issue. As the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated, the modern global market and frequency of air travel allows for the rapid spread of disease. Shutdowns disrupt supply chains, which can lead to price spikes or shortages at the grocery store, and disaster for producers.

The USDA estimates as much as $15 billion in losses from a two-year ASF outbreak scenario, or as much as $50 billion if it couldn’t be eliminated in 10 years.

“They’re just this unstoppable creature that is, from a human perspective, the worst-case scenario of swine.”

The tabletop exercise was held in Washington, where there are not any known standing populations of feral hogs, though they have been found and removed in the past. Feral swine are also in neighboring Oregon, and to a greater extent, California. There are concerns wild pig numbers could be growing in British Columbia following record wildfires. Outside the Northwest, large numbers of feral swine have expanded across the Southern U.S., with the USDA estimating a total population of about 6 million.

Any ASF detection would trigger immediate shutdowns in the pork supply chain. A single infected domestic or wild pig could lead USDA to pause all live pig and semen shipments for 72 hours to try and contain it, a massive stoppage considering we have a million hogs on U.S. roads every day. And being shut out of international trade, even temporarily, is a serious concern.

“As we’ve seen already in some of the places where African Swine Fever has hit, it would just be devastating to not only the economy, but to our producers and to the businesses out there,” said Kevin Morgan, acting deputy assistant director for the Health, Food and Agriculture Resilience Directorate of the Office of Health Security, part of the U.S. Dept of Homeland Security (DHS).

The Office of Health Security was created in 2022 as “the principal medical, workforce health and safety, and public health authority” for the department, building on lessons learned from the pandemic. Officials are currently working on a multi-year risk assessment for the agricultural sector.

“The new national defense strategy for the first time actually elevated issues such as food security and health security to the national security level, as recognition that these things — significant disruptions as we saw with COVID — that can disrupt the food supply, could easily turn into a national security issue if not anticipated, prepared for, and addressed in an all-of-government manner,” Morgan said.

“You get [ASF], it’s an immediate depop, every hog is put down. It’s scary, I don’t care what business you’re in.“

National Security Memorandum-16 (NSM-16), signed by President Biden in 2022, directs federal agencies to ensure the American food system is prepared for future threats. For the Office of Health Security, that means operations like the PNW tabletop exercise, with the goal of building connections and resilience. They’ve run similar gatherings in the Southwest for simulated drought scenarios, and one for Arizona, New Mexico, and California discussing a foot and mouth disease outbreak in cattle.

“We need to get better at shared awareness across borders, because these types of emerging pathogens — there’s no line on a map that they respect,” Morgan said. “We’re in this together, in ways that we can’t afford to be restrictive about that type of thing. We need to be on the same page on surveillance and early warning.”

As the saying goes: You don’t want to be handing out business cards in an emergency.

Beyond building connections, officials are also looking to help producers protect their herds at a local level. Paul Klingeman Jr. runs Pure Country Farms in Ephrata, Washington, an outdoor, antibiotic-free, non-GMO operation of about 400 sows. He’s watched other regional producers go under for years.

But he persists, as his family has for generations. And in some ways, the lack of colleagues is also an insulator. “It’s sad to see, but it’s kind of a blessing,” Klingeman said. “Pig diseases don’t move around as much, because I don’t have to worry about walking into the grocery store and 10 other people having hog boots on, and maybe carrying something back to my farm.”

“How many people are going to think they might get this if they eat pork?”

Still, he takes precautions. He makes 90% of his own feed to reduce the risk of contamination. He runs a closed herd: nothing in or out without supervision. People can’t see other hogs within 48 hours of a visit, and everyone wears special booties. Klingeman also counts on the outdoor setting of his operation to reduce spread of any disease. Workers can’t wear the same boots to fairs, or visit other pigs. It’s extensive.

ASF is not something you can take lightly, Klingeman said. “You can be in business one day and be out of it the next,” he said. “You get it, it’s an immediate depop, every hog is put down. It’s scary, I don’t care what business you’re in. That’s saying your lights are on one day, and your lights are off the next. So it’s a pretty serious ordeal.”

For operations like his, he doesn’t think feral hogs are the number one threat of ASF introduction (contamination of feed would be more likely, he believes). Still, there was a group of feral pigs in the Potholes region a few years back that drew attention. Klingeman more fears the consumer perception impacts of any outbreak — whether human or wildlife driven — much like the Mad Cow crisis in the ‘90s. “How many people are going to think they might get this if they eat pork?” he asked. “I guarantee you pork sales will be down. It’s going to affect everything. It will cause grief on all of us.”

At a higher level, federal officials are running an education campaign to prevent an ASF introduction, reminding travelers that “Pigs don’t fly.” Brown’s team at USDA is also running active ASF surveillance across 12 states — the entire U.S./Mexico border, and the Florida Gulf Coast. But she admits, people’s actions are difficult to anticipate, and disinformation can be a powerful adversary, as they discussed at the PNW tabletop exercise. “It’s hard enough to communicate science to the lay public, much less when you’re competing against social media and Q-Anon conspiracy theorists about how it happened,” Brown said.

This is why relationships could prove to be the most important line of defense if African Swine Fever comes to American shores. Controlling an outbreak would involve not just ecology and epidemiology, but also getting a handle on the unpredictable human component that drives the spread of disease worldwide, especially one with characteristics like ASF. “It’s just a tough bug,” Brown said.