Deer farms have long worked to breed the highest-quality deer for hunting. Is it possible to create a herd that can withstand the plague of chronic wasting disease?

In August 2017, Pennsylvania deer breeder Josh Newton found himself forced to choose between shooting and starving his herd. Three and a half years prior, Newton had sold a doe to a farm in Bedford County, in the state’s southern hills. When a deer in that herd died in 2017 and returned a positive test for chronic wasting disease (CWD), the state Department of Agriculture depopulated and tested all of the other deer in the herd, including the one Newton had sold. When that deer tested positive for CWD, the Department of Agriculture placed Newton’s farm under a 20-month quarantine — essentially a stop order on all business he could conduct, cutting off income to the farm.

“I ended up having to kill animals because I couldn’t afford to feed them,” said Newton. “It was terrible — you go out, you shoot a healthy animal.” When CWD test results from the dead deer came back from the veterinarian, all 26 were negative.

Pennsylvania has the highest number of deer farms in the United States, with 661 facilities. (About 250 of those have five deer or fewer, and are essentially considered hobby farms.) These operations breed and raise desirable specimens of deer for a number of purposes — for materials used in hunting, like deer urine; for venison; and to stock hunting ranches, where customers can pay to hunt deer on enclosed grounds. Newton’s farm outside of Williamsport is one such operation. And regulations to staunch the rampant spread of CWD in the state, which usually entail the depopulation of a herd, have put about half the deer farms in the state out of business.

Tensions have existed between deer farmers and conservationists since the advent of the industry. The latter has long decried the inhumane nature of a “penned hunt,” popularizing the slogan “Real Hunters Don’t Shoot Pets,” and warned against turning a hallowed American way of life into a luxury sport. And yet a few scholars have pointed to the potential ecological benefits of private deer ranches: Where farmers might suffer economic pressures to lease their land for mining, drilling, or other harmful industry, raising deer herds for hunting offers a profitable way to steward healthy forest ecosystems on their land.

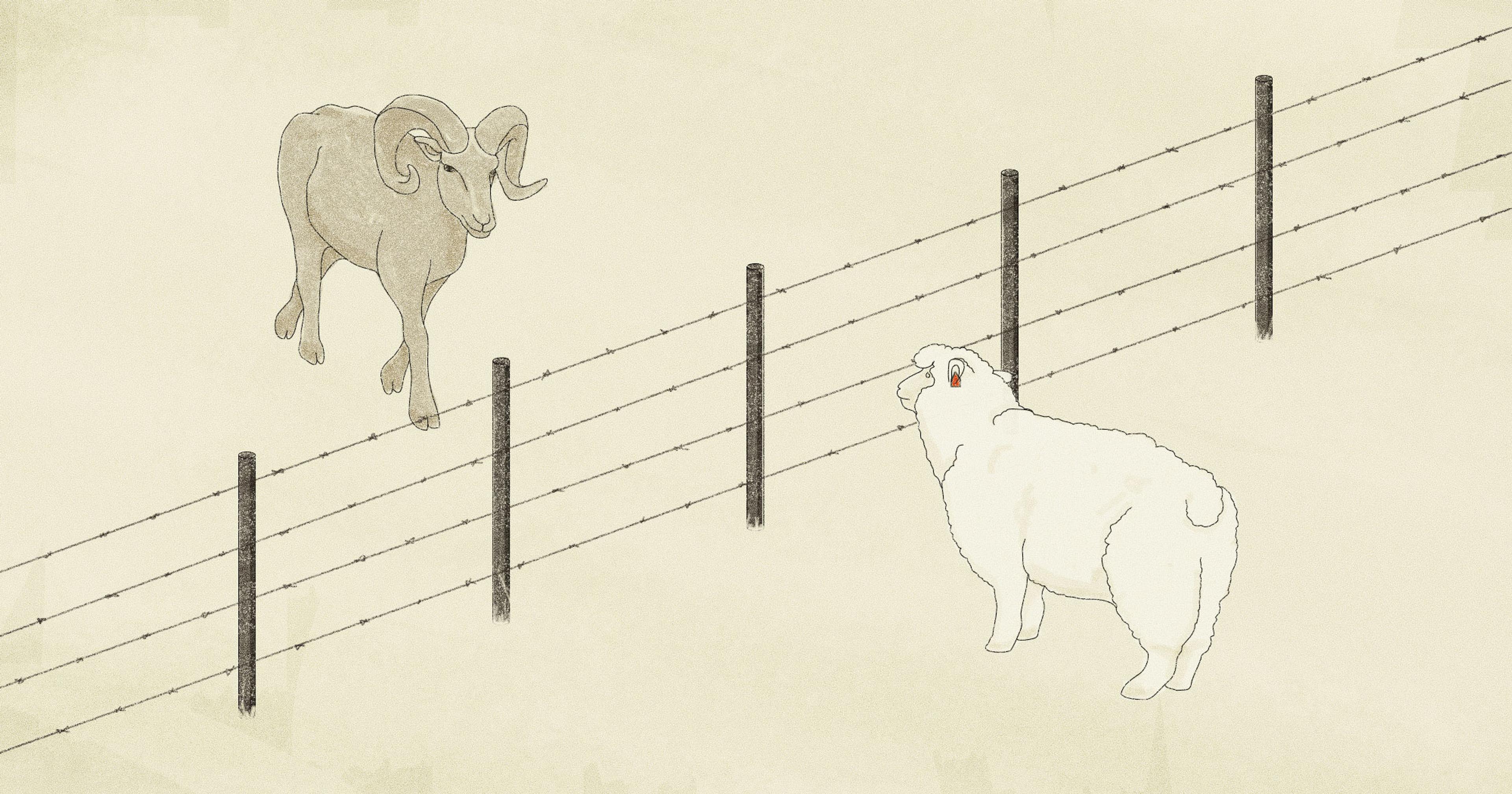

But the explosive rise of CWD, with positivity rates of up to 38 percent in South Central Pennsylvania, has raised another difficult question between the two factions: In a state where wild and captive deer roam their respective woods, which poses more of a threat to the other? Can they safely coexist?

A Disease Unleashed

The late Elizabeth Williams, former professor of veterinary pathology at the University of Wyoming, was the first researcher to identify CWD in 1979. Beginning in 1967, she had observed an illness in captive mule deer in research facilities in Colorado and Wyoming. The deer would show “listlessness, progressive weight loss, and depression … leading to emaciation and death.” They ground their teeth, drooled, drooped their heads toward the earth with slack faces. In 1974, researchers started to perform necropsies on the dead deer, which would show brain and spinal cord tissue riddled with holes and lesions.

They deemed the plague “chronic wasting disease” and placed it in the same category as scrapie, mad cow, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob — degenerative conditions of the nervous system that affect sheep, cows, and humans, respectively. These diseases spread through prions, misshapen proteins that alter the makeup of cells and erode brain and spinal tissue over the course of years.

There’s no firm conclusion on how those first mule deer became ill. Theories include that they could have arrived at the facility already infected from the wild, or they could have contracted a species-jumping version of the scrapie virus from sheep in a shared facility. The first wild deer to be diagnosed with CWD was found in Rocky Mountain National Park in 1981, two years after Williams’ landmark paper was published. In the years that followed, the disease spread across the continent. It was first reported in Pennsylvania in 2012, in a deer that died on a farm in the South Central part of the state, and there have been over a thousand positive cases reported in both wild and farmed deer since.

Farmers buy and sell deer for breeding or to develop herds to hunt, which means there’s more wide-ranging movement among captive facilities than in the wild, and more opportunity for infection to travel. (Josh Newton, like a number of other farmers, has maintained a “closed herd” since 2015 out of concern for CWD quarantine.) It’s also — obviously — easier to test captive deer than wild ones, which results in more positive tests on farms.

“I think many in the wildlife and conservation agencies look at the deer farming industry as an industry that is exploiting wildlife for profit.“

But CWD can make its way to a healthy deer any number of ways. It can transfer between wild and captive herds when captive deer escape, or through the barriers of single-fence (as opposed to double-fence) facilities. It can also travel through smaller and less controllable vectors: carrion birds who eat infected meat, mice and voles, plant matter and soil, even tufts of fur left in the bed of a truck.

“Nobody really knows how it got started, and with any positive detection it’s hard to say how it got there in the first place,” said Andrea Korman, CWD biologist with the Pennsylvania Game Commission.

The spread of the disease has also augmented tensions between hunters and farmers in the state, with each pointing fingers at the other as perpetrators of its spread. “The wild deer resource is in jeopardy, and hunters aren’t happy,” said Kip Adams, chief conservation officer with the National Deer Association, “because once the disease ends up in a new area, all hunting regulations change.”

The Pennsylvania Game Commission has designated seven Disease Management Areas (DMAs) in the state, five of which originated from a positive case on a captive facility. State restrictions surrounding the DMAs include prohibiting hunters from taking high-risk parts of the carcass — like the head and the spine — from outside DMA borders without first sending them to a state-licensed processor for testing. And, of course, the worst-case fear is that CWD could eventually wipe out wild deer populations.

“I think many in the wildlife and conservation agencies look at the deer farming industry as an industry that is exploiting wildlife for profit, and they don’t believe we can do what we do,” said Newton. “Starting from that premise, there’s been an ideological divide — to say deer farming is bad and it shouldn’t be legal, and then you add the CWD into that convo, and it becomes a larger finger pointed, [saying] we’re the reason CWD is spreading.”

The Trouble With Tests

The challenges of containing CWD, especially with regard to the deer farming industry, have to do with testing. A reliable, easy-to-execute test that could be performed on live animals would make movement of deer from farm to farm safer. The most common and reliable test — an analysis of the brain stem or the retropharyngeal lymph nodes — is performed after a deer has died. There are live tests, but they’re invasive and somewhat challenging to execute, and not effective at detecting the disease in its early stages.

Another approach, first implemented to address scrapie in sheep herds in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands at the start of the 2000s, entails identifying CWD-resistant genomes and selectively breeding susceptibility out of herds. Deer farms already make a business out of breeding for size and — somewhat infamously — enormous antlers. It makes them an apt testing ground for breeding CWD resistance.

In 2020 Christopher Seabury, professor of genomics at Texas A&M University’s veterinary school, published a paper identifying genomic traits associated with resistance to the disease. “We find that most of the variation in susceptibility and resistance can be explained by genetics,” he said in an email. “And our research continues to show that less than 1 percent of the farmed white-tailed deer with “resistance genetics” (as defined by our program) ultimately test positive for CWD at CWD-positive facilities nationwide. Moreover, the genetics which afford this ‘resistance’ to CWD are also common among farmed white-tailed deer.”

Using Seabury’s research, Josh Newton has begun to use DNA testing to breed susceptibility to the disease out of his herd. He’ll submit tissue samples from his herd — a small piece of skin taken from a deer’s ear with a tool like a hole punch — to the North American Deer Registry, which uses technology developed by Seabury to identify a number of genetic markers in the tissue’s DNA, including CWD susceptibility.

Josh Newton has begun to use DNA testing to breed susceptibility to the disease out of his herd.

From that report, he can determine how strong of a candidate that deer is to breed. “We have our industry pushing as hard as we can to educate our fellow producers on the value of this and then get them to implement it,” Newton said. “We have this tool today through this technology, that eases our regulatory burden because we’re going to beat or solve this disease.”

Many wildlife biologists are more skeptical of the power of selective breeding to alleviate the disease in wild herds. In April, the Oklahoma state legislature passed a bill that would support a 2026 pilot program where captive deer with CWD-resistant genes would be released to breed with wild ones — which has been met with considerable uproar.

There’s no genome that has proven to be immune to CWD, but deer that are CWD-resistant don’t contract the disease as easily, and live longer once they have it. Seabury points out that breeding for scrapie resistance — not immunity — in sheep herds has been effective in reducing the disease significantly in the United States. That’s in combination with practices like frequent testing and monitoring for symptoms, depopulating infected animals, and controlling the movement of herds.

But it’s obviously much harder to control breeding in wild populations, let alone movement and symptom monitoring. And even as evolution might favor CWD-resistant genes, that process is very slow.

The selective breeding technology “works very well inside a fence,” said Adams with the National Deer Association. “That is not the future for wild deer herds.”