The state will now pay livestock producers for their animals‘ indirect, wolf-related stress.

Ranchers in Western states have had a predictably rocky relationship with predators like wolves and grizzly bears. In particular, livestock owners in wolf territory have to remain on high alert to protect their herds and their livelihood.

In some states, like Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming, ranchers can shoot wolves on sight if they are threatening livestock. In others, like California, killing wolves is illegal — they were relisted as endangered last yeard — and ranchers and wolves must learn to coexist.

In an effort to aid the ranchers who deal with the impacts of wolf presence, states like New Mexico, Oregon, and California started programs that pay them back for financial burdens of losing their animals The programs offer reimbursement for direct livestock loss due to wolves or non-lethal on-ranch tools — like fences, guard dogs, or even extra staff.

Now, thanks to an expansion of California’s pay-back policy, ranchers are entitled to more wolf dollars than ever.

California’s program — originally launched in February 2022 by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) — took an extra step last month, offering ranchers reimbursements for indirect impacts of the predators’ presence. These impacts include wolf-induced stress that can result in reduced weight or breeding problems — no other payback program is so comprehensive.

When CDFW originally launched the Wolf-Livestock Compensation Program, ranchers could get payments for direct livestock loss, meaning if they found one of their animals injured or dead thanks to a wolf, the program would provide compensation. The exact payout for each animal is based on what it would sell for at full market value, which can be dependent on weight and type. For example, the payout for a typical head of cattle can be worth anywhere from $2,000-$3,000, and sheep around $100-300.

If they implemented special structures like fencing, hired extra help to protect herds, or bought guard dogs, reimbursement was available for that too. And if a rancher’s guard dog falls victim to a wolf, they would be repaid for it, too.

There are also more colorful techniques to deter the wolves. A method called fladry, for example, involves stringing brightly colored flags around the perimeter of the livestock. The flags fluttering about leave the wolves wary, and can be enough to keep them away. Some ranchers double down by stringing the flags along electrified wires.

Vicky Monroe, the department’s statewide conflict programs coordinator, said the CDFW “understands that livestock producers operating within wolf territories may be impacted directly and indirectly by wolves.” For the indirect loss, the state uses a calculation that pays for up to 3% of an animal’s value if that animal resides in wolf territory. So, say a rancher has 10 $2,000 cows living in a wolf pack’s main stomping ground, a rancher may be entitled to $600 per year in compensation for the cattle’s potential stress.

“We’ve got one rancher that’s lost nearly 20 animals since these wolves came.”

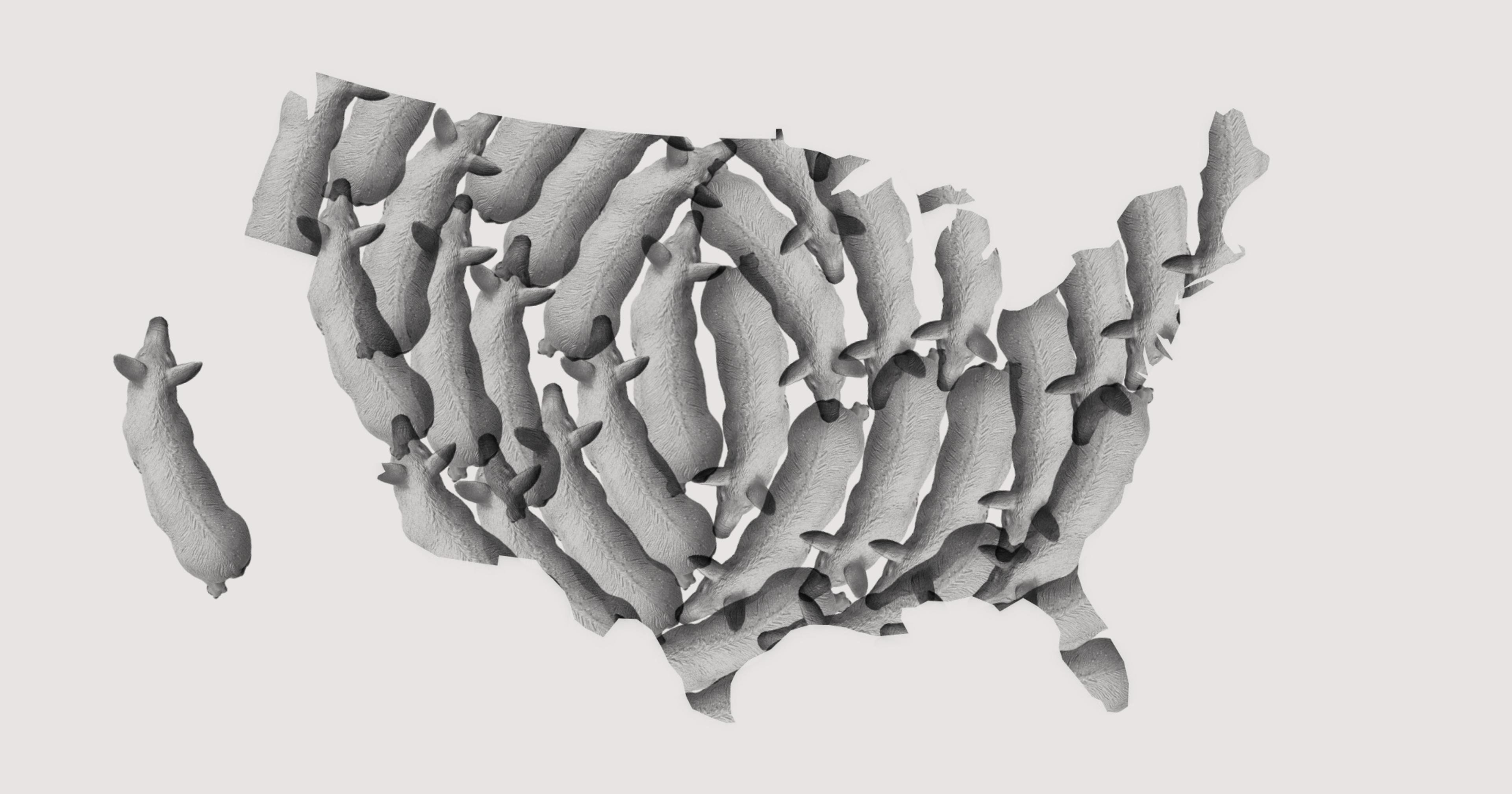

Even though wolves only account for 1% or less of accidental livestock deaths around the country, some ranchers are impacted more than others. That’s certainly the case for wolf territory in northern California like Siskiyou and Lassen Counties, where the Cascade mountain range region houses an abundance of both wolf packs and ranches.

Pat Griffin, once Siskiyou County’s agricultural commissioner, currently serves as the region’s wolf consultant. A cattle rancher himself, he has never lost any livestock to wolves, but he’s seen how hard it can be for ranchers who do. “If you look at it on a statewide basis, there’s a very small percentage of ranchers who are affected. But for those ranchers here locally that are impacted, it can be significant. We’ve got one rancher that’s lost nearly 20 animals since these wolves came.”

Other states, like New Mexico and Oregon, also have reimbursement programs. But California’s program is the only one in the nation that covers ranches for all three types of reimbursement: direct loss, indirect loss, and the use of non-lethal wolf deterrents.

Programs in other states also have less funding to work with, meaning payments have to be split or prorated amongst all qualifying applicants. “Here, right now, they’re doing 100% payment for the approved applications. I don’t think any other state has the level of funding that we have,” said Griffin.

That being said, California’s program is not permanently funded. Instead, it is a pilot program, based on $3 million of allocated state funding. As of now, the program only runs until June 30, 2026, or until all funds are used.

If a rancher discovers one of their animals killed, they have to ask for an investigation into that death.

To receive funds, ranchers have to submit applications to the CDFW website for approval. Repayment requests for non-lethal deterrents are the most straightforward. If a rancher pays for any equipment or structures to deter wolves, they fill out a form and submit receipts to get the money back.

A rancher seeking reimbursement for direct wolf-related losses needs to come bearing proof. If a rancher discovers one of their animals killed, they have to ask for an investigation into that death. And factors like finding a carcass too late, or never at all, can make proving a wolf killed the animal more complicated.

Griffin explained that when a rancher requests an investigation, either county trappers, wildlife biologists with CDFW, or he himself can carry that investigation forward. “If there’s evidence that shows that it was a wolf kill, that rancher can be reimbursed for the fair market value of that animal at the normal time of sale,” said Griffin.

The “normal time of sale” is another important aspect of the reimbursement program. With that language, even if a rancher lost, say, an 80-pound calf that was worth only hundreds of dollars at its time of death, the rancher can get paid the thousands, or whatever market value it would have been worth when fully grown. That is, of course, as long as it’s a “confirmed or probable” wolf-related death, approved by the program.

For the new, indirect part of the program, the state uses calculations based on the wolves usual whereabouts to determine what the region’s “core area” for the predators is. Through the program, ranchers are entitled to payments ranging from 2-3.5% of each individual animals’ market value, if that animal is living on or near wolf territory. This hopes to cover the harder-to-quantify, indirect impacts of the wolf’s presence — a gray area that’s still being researched.

“Once you compensate me for the wolf kills, it’s like agreeing that it’s okay.”

Tina Saitone, a UC Davis Cooperative Extension agricultural economist leading a study to quantify the impact of wolf presence on cattle performance and grazing behavior said in a statement, “Fear of prey stimulates cortisol production, so high concentrations of cortisol after leaving high-elevation ranges could suggest that wolf presence is correlated with cattle performance and indirect economic consequences.” She noted that stress also impairs cattle’s immune system and reproductive abilities.

For some ranchers, taking the state money feels less like a solution, and more like accepting a preventable problem.

Billie Roney, a cattle rancher with her husband Wally in Lassen County who no longer runs calves due to multiple wolf depredations, told Ag Alert, “Once you compensate me for the wolf kills, it’s like agreeing that it’s OK. The other side says, ‘It’s no big deal,’” Roney said. “That’s the part I’m not OK with.” Presumably, Roney may favor a shoot-on-site policy like in Wyoming or Montana.

Still, the program is considered popular, a compromise that allows for the protection of an endangered species while easing the financial pain of livestock owners. Monroe said that, to date, the CDFW has processed a total of 42 applications from 21 individual ranchers seeking over $750,000 in payments.

And Griffin said despite the mixed opinions, he can see the program’s potential as a source of solid payment for ranchers.

“Some ranchers … are pleased to get it, but not everybody. And I’m not sure everybody’s going to apply. But it could be a significant payment,” said Griffin. “I think ranchers really need to look at it as a means to offset the extra burdens they are having to bear to have these animals present.”