As avian influenza moves from birds to cows to people, how worried do we need to be?

As farmers around the country struggle with avian flu infections in their livestock, health agencies raised alarms this week when they confirmed that at least one person had contracted the virus. And while this strain of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), also known as H5N1, has long impacted wildlife and commercial poultry flocks, scientists are significantly more concerned with the virus’s jump to humans and domesticated mammal species, including cows in nearly a dozen dairy herds across four states, and a goat in Minnesota.

The Texas dairy worker diagnosed with HPAI is only the second case ever recorded in humans in the U.S. Up until last month, it had never been observed in cows — but as of Tuesday, the USDA confirmed HPAI had been detected in seven Texas dairy herds, two in Kansas, and one each in Michigan and New Mexico, with one other herd in Idaho still pending results from the National Veterinary Services Laboratories.

Richard Webby, director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds, said that while there’s still a lot we don’t know about the outbreak, the risk for “the average person on the street” hasn’t increased at all. For farmworkers handling livestock, however, it’s another story. The patient diagnosed in Texas worked directly with a sick dairy cow, according to the New York Times, and is being treated for conjunctivitis, or pink eye. To avoid the spread of disease, the CDC is recommending gear like gloves, goggles, and disposable boots.

This HPAI strain has been around since 1996, Webby said, when its “great, great, great grandparents” originated in Southern China. Since then, the virus — which is carried by wild, migratory birds — has mutated somewhat. But in its current evolution, it’s still not very well-adapted to mammal hosts, meaning it’s less likely to be deadly or otherwise severe. Though an 11-year-old girl died last year from avian flu in Cambodia, in the U.S. the most acute cases of mammalian HPAI have occurred in the wild among scavengers that ingest infected birds — think foxes, bears, and raccoons. In humans and domesticated animals, the infections have been much less severe because the virus can’t survive well outside the respiratory tract.

Still, “if there’s any virus I don’t want, it’s this,” Webby noted. And for good reason: For some severely sick wildlife, the virus can migrate outside the respiratory tract to impact other organs, including the brain.

Now that domesticated ruminants like goats and cows are getting infected, more people will be exposed to the virus than in previous outbreaks. But, unlike wild creatures, farm animals live in controlled populations that can be monitored closely — which is exactly what scientists and farmers need to do in order to understand more about and contain the outbreak, Webby said.

Phillip Jardon, clinical associate professor at Iowa State University and veterinarian at the school’s dairy extension, said before the last several weeks, HPAI wasn’t something experts thought to test for in cattle. But after months of attempting to identify a “mysterious” disease affecting milk production in Texas dairy cows, veterinarians and researchers were stumped. Jardon and his colleagues in Iowa were among those tapped to try to figure out what was making these cows ill. But it wasn’t until the carcass of a young goat in Minnesota tested positive for HPAI on March 20 that they even considered testing cows.

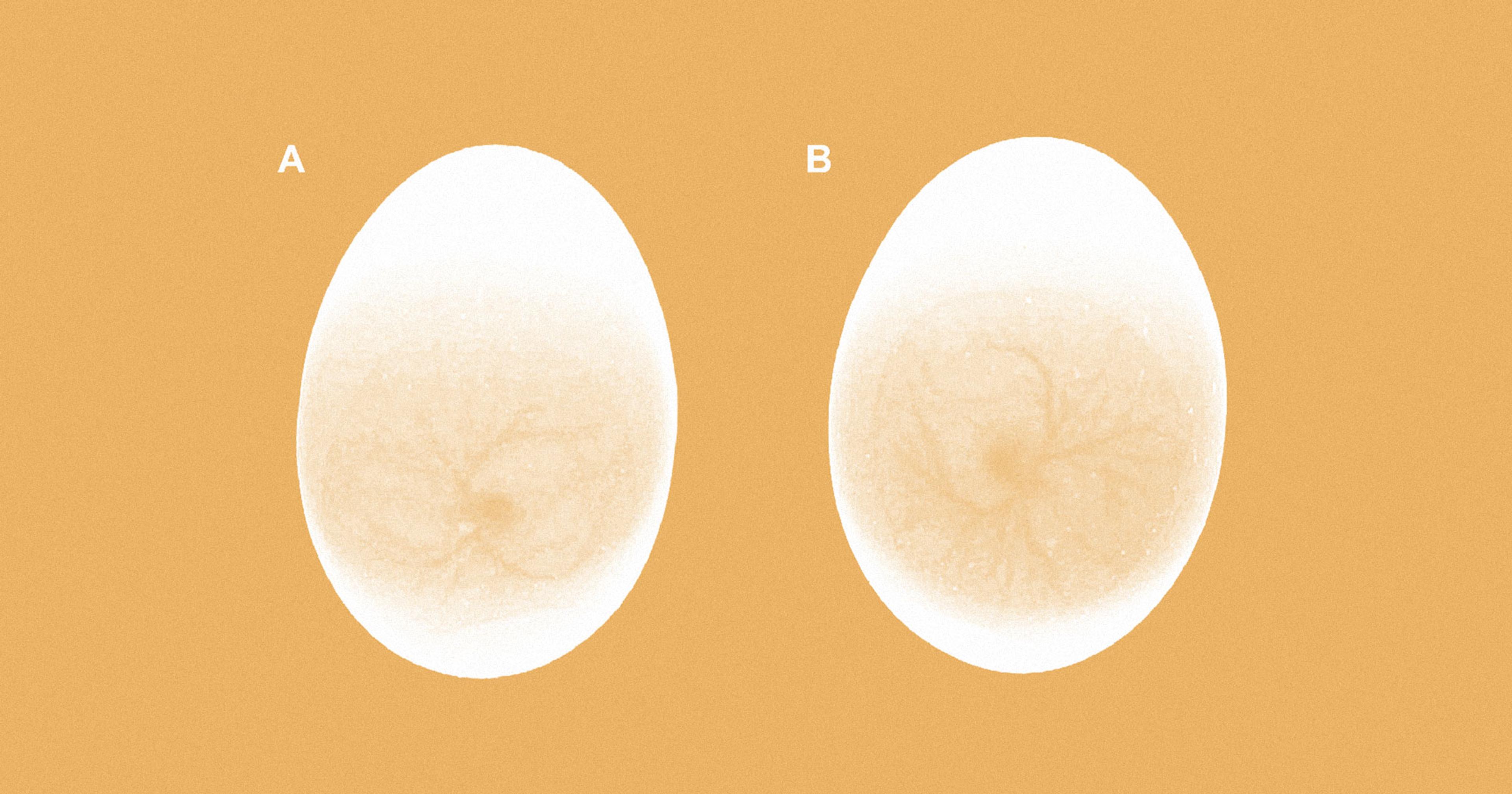

Researchers don’t know yet whether certain animal demographics are more at risk than others. In cattle so far, only mature dairy cows have presented HPAI symptoms — including decreased lactation and appetite. And while the standard response to a diseased poultry flock is to cull the animals indiscriminately — at least 2 million laying hens were “depopulated” in Texas this week — the vast majority of infected cattle are expected to make a full recovery. Some farms, however, are killing off cows whose milk production doesn’t bounce all the way back.

Jardon said it’s actually easier to prevent the spread of HPAI in poultry than it is in cows, which are about as difficult to quarantine as “a bunch of kindergarteners.”

“If there’s any virus I don’t want, it’s this.”

It’s harder to keep wild birds out of cow barns and away from cattle feed than it is to keep them out of chicken coops, he said. And while there’s talk of a vaccine for poultry, there isn’t the same push for cattle. “For some diseases, vaccines are magical, like for rabies,” Jardon said. “Some other vaccines are not as effective,” because the virus spreads quickly through a herd and can change rapidly.

The dairy industry is watching closely as events unfold, though so far there have been no dramatic fluctuations in the market. Sick cows produce significantly less milk, and what they do produce must be discarded, but Jardon said roughly only 10% of affected herds are experiencing symptoms. The CDC has strongly advised consumers to avoid raw dairy, which is only legal in a handful of states, because of potential contamination, but Jardon — who grinned and sipped a glass of store-bought milk on camera over Zoom — emphasized that pasteurized products remain safe.

In the shadow of the Covid epidemic, nerves are high. Some are wondering if this outbreak could trigger a global health crisis on a similar scale, or even a mass extinction event. Left unchecked, “that’s absolutely a possibility,” Webby warned. An industry dominated by factory farms focused solely on “the fastest way to convert feed into meat” does “create many more opportunities for a virus to get in and spread throughout that population,” he added.

The “extreme end” of this HPAI outbreak could look like “another Covid-level crisis,” wherein the avian flu virus will mutate enough to be “more able to transmit between humans, and we have another pandemic.”

Webby’s former colleague at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Robert Webster, who has since retired, expressed his concern last year that not enough people were taking the “inevitability” of the human-to-human transmission of H5N1 seriously.

“I think there’s an attitude like, ‘This virus has been wrapped for 30 years, so why are we getting our knickers in a twist at the moment?’” he said. “But consider the fact [the virus] acquired the ability to spread throughout the whole world and that hadn’t happened before. I think we need to be ready for anything.”

But while outbreaks like these are scary, they don’t immediately spell doomsday. In the more than 25 years that this virus has been circulating, there have been close to 1,000 human cases overall and infections in several different mammal species. In all that time, Webby stressed, we haven’t really seen much of a change in the virus. It’s not that catastrophe is impossible, it’s just not inevitable.

“There certainly are schools of thought that this particular form of flu can’t be a pandemic virus in humans, but I think it probably can,” Webby said. “I just think the barriers for this virus to overcome, to become a fully fledged human pathogen, are fairly high. It would have to make some changes that this virus really doesn’t want to make.”