The U.S. Navy owns more than 50,000 acres of forest in Indiana. They use some of the wood to maintain their oldest warship, the USS Constitution.

Trent Osmon began working at a landlocked Indiana naval base in 1997 while earning his forestry degree. He knew the work might entail long days of walking through the woods to collect data on trees and wildlife. What he didn’t realize when he started the job was that he wouldn’t just be assessing the health of trees; he would be sizing them up for use in the restoration of the world’s oldest warship still afloat, docked in a harbor over 1,000 miles away.

Since 1976, the U.S. Navy has relied on white oak trees grown amid more than 50,000 acres of forest on the Naval Support Activity Crane in Crane, Indiana, to maintain the USS Constitution, often referred to as “Old Ironsides.” The Constitution is the last of six frigates commissioned by George Washington in 1794 to establish the Navy — it first set sail in 1798. Today, the massive ship is docked in the Charlestown Navy Yard in Massachusetts, where hundreds of thousands of people visit it and attend tours led by active duty sailors every year.

The storied warship is almost always undergoing some kind of repair or maintenance, according to Margherita M. Desy, the ship’s official historian employed by the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston. That ongoing maintenance requires very specific materials, and is the reason the Navy relies on white oak trees from Indiana.

“The procurement of appropriate wood for historic wooden vessels is actually quite an issue in the maritime world,” said Desy. “We’re all always looking for wood of the dimensions that we need.”

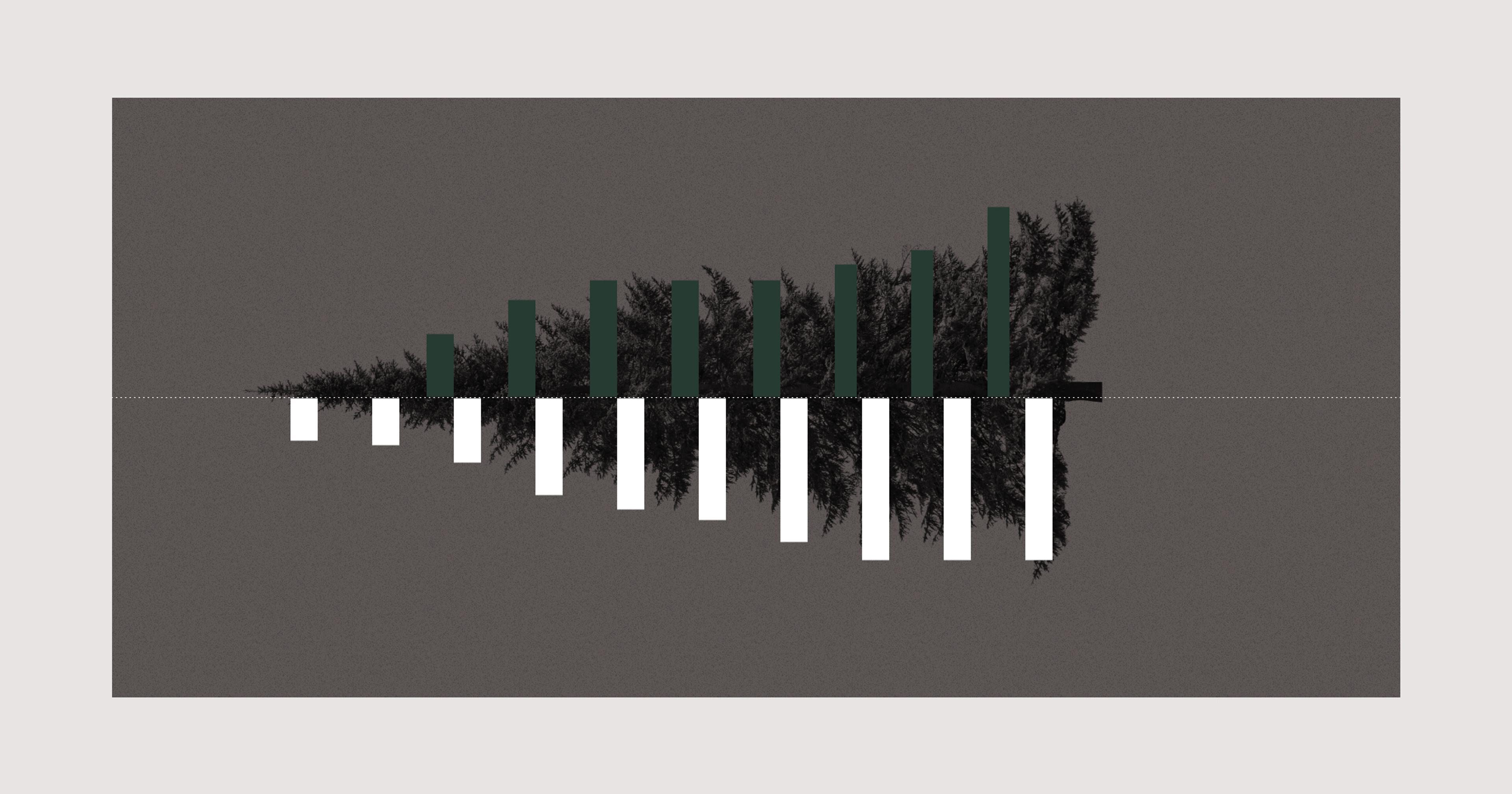

In the case of the Constitution, those dimensions are enormous: To be of use for the ship’s hull, the white oaks have to be at least 40 inches in diameter at their base, and at least 40 feet long from base to crown, according to Desy. They also have to be extremely straight. That’s where foresters like Trent Osmon come in.

While today Osmon spends most of his time inside overseeing a team of foresters and environmentalists at Crane, he spent the first 18 years of his career in the field, tending to the forest. Two groves within that forest are predominately white oak; there are also about 120 more white oak scattered throughout the property that Osmon and his team have identified, mapped, and monitored for their shipbuilding potential.

“When we are just in our normal day to day forestry operations, we manage the forest independently of the Constitution just for biodiversity,” said Osmon. “So when we come across a big beautiful tree, we’ll GPS it, and we can go out and relocate them.”

When he first started at Crane in the late 90s, Old Ironsides was undergoing repairs in preparation for its 200th birthday celebration. The naval base sent 78 white oaks to the East Coast for the restoration, and Osmon, a self-professed history buff, was delighted to learn this would be part of his job.

“The procurement of appropriate wood for historic wooden vessels is actually quite an issue in the maritime world.”

“It was big in the news, there was a lot of buzz around here because we knew that Crane had provided the wood,” he said. In 2015, when the next restoration took place, Osmon and his team selected 35 trees for the ship, and he escorted the first load out to Boston.

Beyond keeping an eye for trees that might be candidates for the Constitution, Osmon relished spotting wildlife while bushwhacking through the forest at Crane.

“Sometimes you see some stuff that most people don’t get to see very often, whether it’s bug species or even a snake species or a frog species, or even a little bird,” he said, adding that the scarlet tanager is one of his favorite songbirds to spot.

In their maintenance of the forest, Osmon and his team are also charged with protecting an endangered species: the Indiana bat. During the summer months, these rare little bats roost under the bark of trees like the Shag Bark Hickory, or the shards of bark that loosen on dead trees. Osmon ensures the hickory are never cut down, and his team sometimes intentionally kills damaged trees to create more habitat for the bats. They also refrain from cutting down any trees from April until October, when the bats head into caves to hibernate for the winter.

“Each of those trees is an ecosystem in and of itself,” said Osmon.

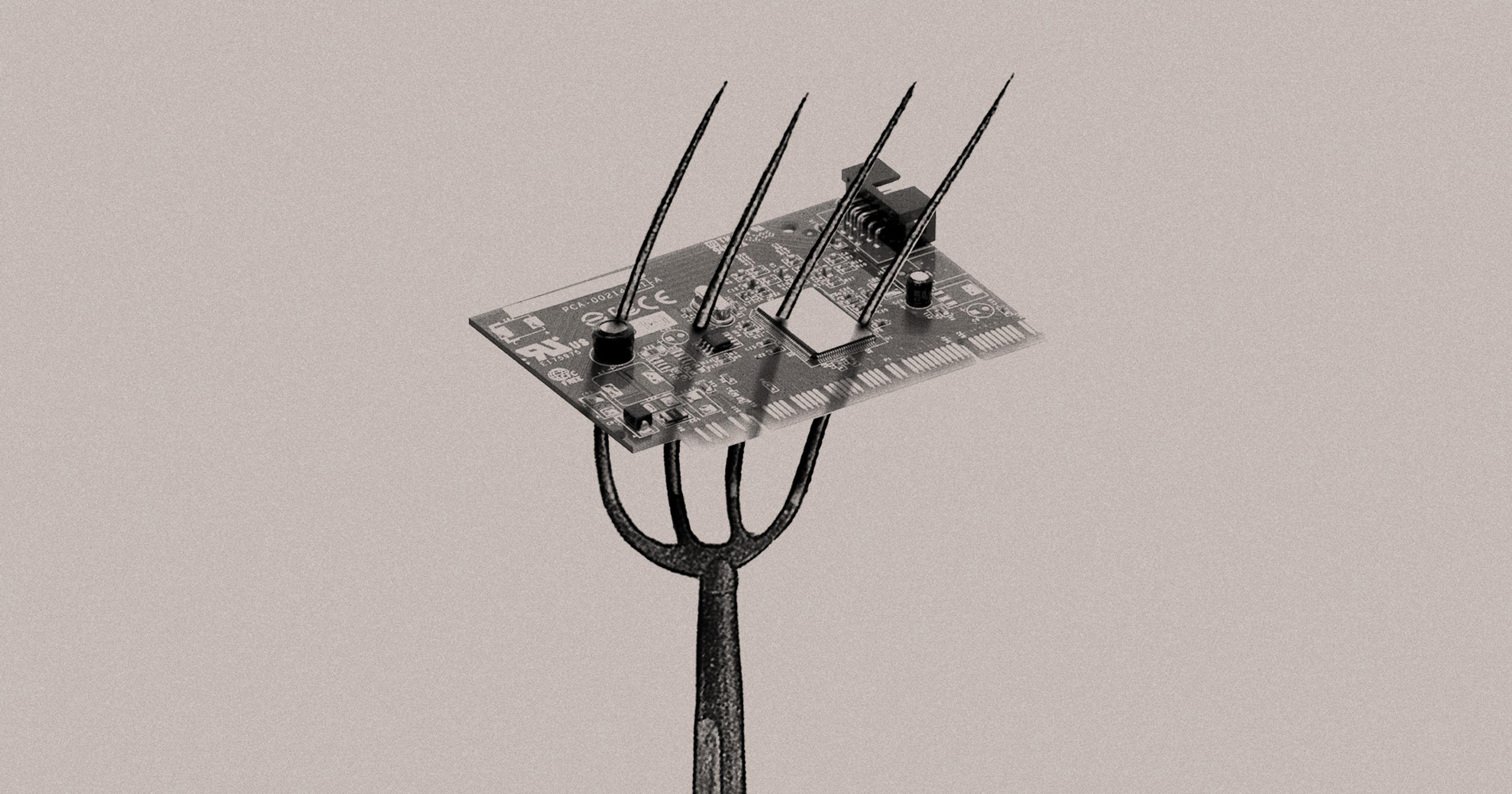

Part of Osmon’s job entails negotiating with fellow naval staff who are looking to test military equipment such as electronics and radar equipment. Osmon works to mitigate the environmental impact of this testing; he might require staff to test during the day when the bats are asleep or in the winter when they’re hibernating, for example.

“The perception is a military base is all blacktop and buildings, but some of these bases are enormous.”

Osmon also works closely with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, who act as a regulatory agency when activity at Crane could impact an endangered species. He’s currently working with them to create habitat for monarchs, planting milkweed and prairie plants to accommodate their larvae. And the water in a manmade lake on the base is so clear thanks to the health of the forest, it is populated by a rare freshwater jellyfish otherwise unseen in typically murky Midwestern bodies of water.

This delicate management and conservation of habitats and the broader forest ecosystem may not be what springs to mind for most people when they think of our armed forces, but the Department of Defense (DOD) is charged with tending to ecologically diverse landscapes across the country. While environmental conservationists and the military may seem like odd bedfellows, their goals are often intertwined, even as their core missions diverge. During the Trump administration, for example, former defense secretary James Mattis cited climate change as a major threat to national security.

“Some of the most diverse landscapes are within military landscapes,” said James Lewis, staff historian for the Forest History Society. “The perception is a military base is all blacktop and buildings, but some of these bases are enormous,” he added. “They need training grounds with different conditions.”

While vast swaths of land overseen by the military may be protected from some of the harms of urban development and clear-cutting for agriculture, this stewardship can also come with its own environmental impact. Certain trees at Crane, for example, are full of shrapnel from ammunition testing, according to Desy. Shells and artillery remnants on bases can leech toxins into soil, and military training exercises involving large vehicles can reduce plant cover and leave soil compacted.

For Osmon, the environmental task at hand coexists alongside the hunt for trees for Old Ironsides and his colleagues’ tasks of testing lasers, radars, and other military tools. As private land is developed and species of flora and fauna are pushed onto DOD lands, experts like Osmon are essential caretakers.

“That rapid development outside the fence line is pushing a lot of these species on our property,” he said. “And so the DOD is partnering to try and help preserve those species. As they become more and more endangered it restricts the [military] mission that much more. Kind of an interesting dance.”