Steeped in a rich history, Black oystermen and women across U.S. coastal regions have been disappearing for decades — a revival may be underway.

When Baltimore restaurateur Jasmine Norton set out to partner with a Black oyster farmer, sourcing was a lot more difficult than she’d imagined.

“There generally isn’t a lot of widespread coverage of Black oyster economies and farmers,” said Norton, chef and owner of Baltimore’s The Urban Oyster Bar, the country’s only Black-and-woman-owned oyster restaurant. “A lot of our industry connections are made by word of mouth and the legacies are often shared through the oral tradition, but not much has been written down or documented in a way that gives new generations access to this information,” she continued.

Norton acknowledged that her own path to oysters was forged by a legacy of Black oystermen and women — shuckers, dredgers, and especially farmers — who helped build today’s billion-dollar industry in the United States.

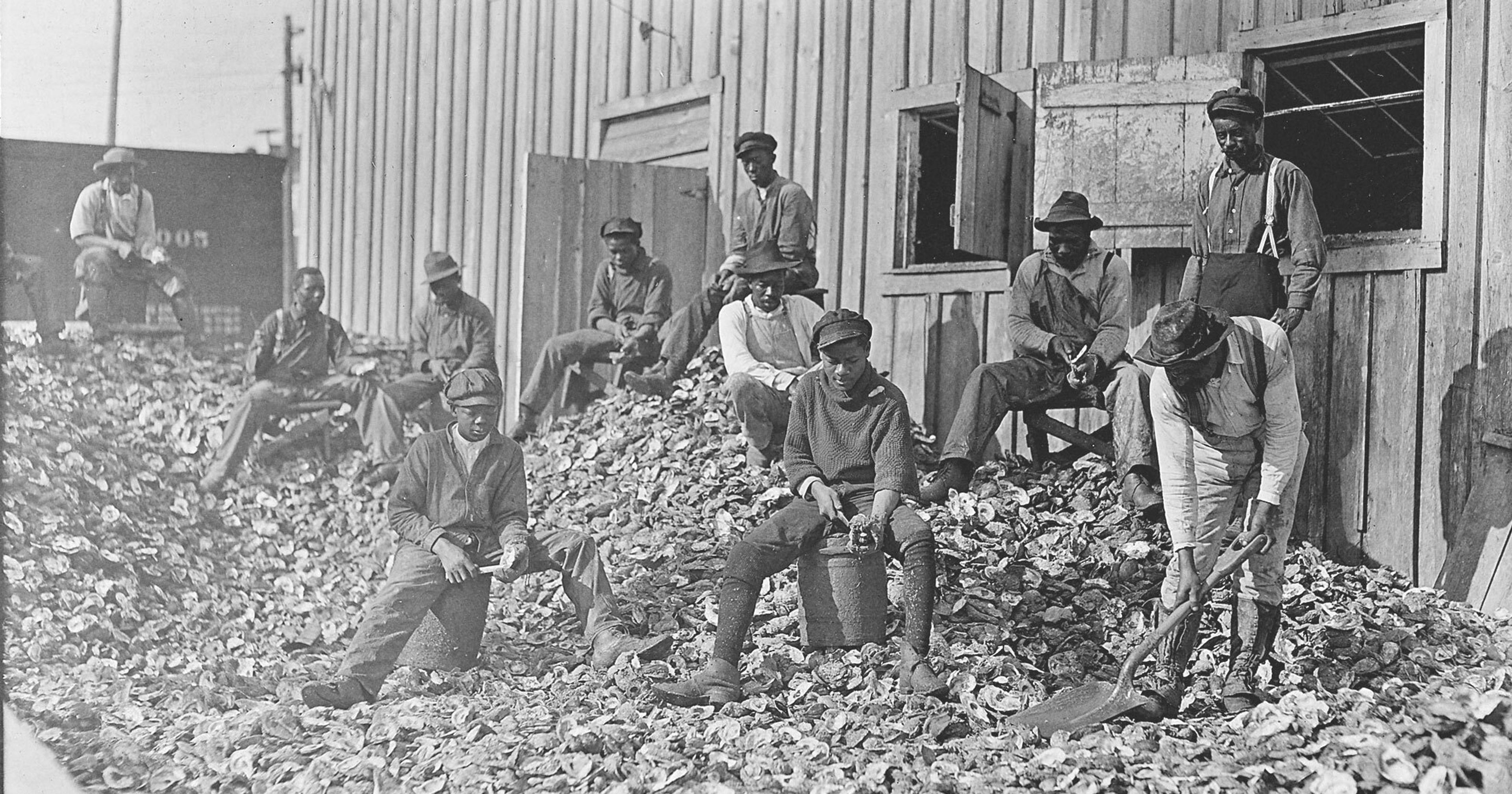

Similarly, in other coastal regions of the United States such as New Orleans, Maryland’s Eastern Shore, South Carolina, and Georgia, the contributions and expertise of Black oystermen and women during The Gilded Age were critical in building the American oyster industry. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, in the 1880s, oyster farming peaked to around 27 million bushels per year. Oysters were a common food, especially throughout the East Coast and Midwest. Thousands of industry workers were involved in the process from harvesting to shucking, dredging, canning, packing, and transporting.

However, many Black oystermen and women during this time traced their involvement in the industry back to the pre-and-during Civil War era when Blacks and Whites often worked the waterways together. Still, Black oystermen and women of coastal communities were often taken advantage of by enslavers who used them to farm, sell, clean, and prepare oysters, but paid them little to nothing at all.

In the Netflix docu-series High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America, host Stephen Satterfield highlights Thomas Downing, “The Oyster King of New York,” who became famous for his NYC oyster business in the late 1800s. Learning the ropes from growing up on Virginia’s eastern shore, Downing’s Broad Street oyster cellar assisted in elevating the business of oysters, taking them from cheap, easy-to-afford eats for the working class to fine-dining delicacies. Located near Five Points and the center of the city’s bustling business district, oysters ironically became inaccessible to the very people who helped to build their popularity.

Despite his own community’s lack of access to oysters, Downing expanded his business to include catering and shipping nationwide. His pickled oysters even made their way to Queen Elizabeth in Europe. The queen was so pleased, she sent Downing a gold watch that became a treasured family heirloom.

This popularity, in turn, gave Downing the platform as an activist for New York’s free Black community, fighting alongside local civic organizations for economic equity — a legacy that was passed down to his eldest son, George Thomas Downing, who was also a hotelier, activist, and restaurateur.

After the Emancipation Proclamation, Black oyster harvesters looked to the fishing industry as means to financially support themselves and their families. At the time, oystering was one of the highest paid professions for Black men. By the early 1900s, many areas along the Eastern Seaboard were renowned for robust oyster harvests. The Department of Labor even noted in its yearly bulletin that Black oyster harvesters were thriving in oyster and fish-producing areas like Litwalton and Whealton.

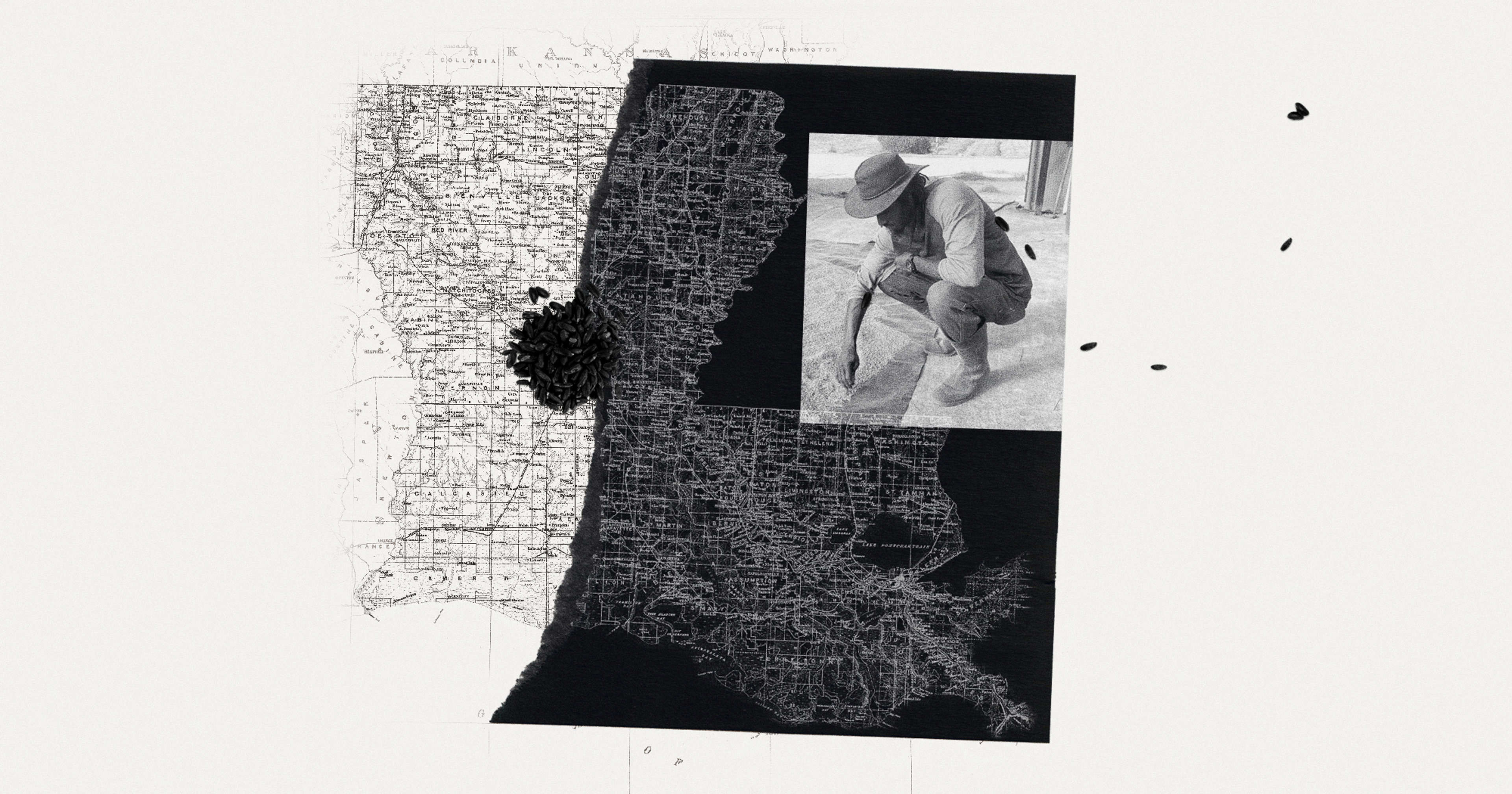

During the Reconstruction era, Black oyster farmers in the South (the Carolinas, Georgia, Louisiana) often entered into sharecropping-variety agreements that kept Black Southerners impoverished and immobile. In response, many made their way North to form communities like Sandy Ground, an oyster harvesting sanctuary in Rossville, New York.

Promoting Sustainable Communities

Historically, oyster farming supported sustainability not only within the industry, but also within predominantly Black communities.

“The economic impact of the oyster farming process affects individuals and businesses on several levels,” said Kevin Dawson, associate professor of history at the University of California, Merced, and author of The Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora. Dawson has dedicated his life’s work to examining aquatic culture amongst West Africans and Africans in America during the late 15th century through American Reconstruction.

“My current work in progress closely examines how enslaved African women used fishing techniques to sell all kinds of seafood, including oysters, at what would be known as modern-day farmer’s markets,” said Dawson.

“During the early and mid-1800s, most of what was being eaten in seaports was being produced by enslaved people during their free time. They were fishing, crabbing, harvesting oysters and selling it in port cities like Baltimore, Charleston, and New Orleans. Oysters, in addition to other types of seafood, were really crucial to those economies,” emphasized Dawson.

In his research, Dawson discovered that these women were often allowed to keep their profits. However, enslavers used this system to justify not giving the enslaved enough clothes to wear or quality food to eat.

“A universal complaint was that enslavers did not provide them with enough clothing and food … so women used profits from selling oysters to buy necessities like clothes, bedding, bathing, and hygienic products in addition to small livestock for meat and eggs,” explained Dawson.

Another such story is that of John and Tom Vreeland Jackson, two brothers who, in 1830, were freedmen in the Hudson River region whose oyster business funded the purchase of family land and served as a refuge for enslaved Africans escaping through the Underground Railroad.

Oyster harvesting continued to support generations of families by providing stable and steady work. For instance, Ira Samuel Wright of Wetipquin, Maryland, worked as an oyster farmer from the 1950s to the mid-70s. Oystering the Chesapeake Bay, just like his father had done before him, Wright earned a solid income for himself and his family.

Dawson continued, “Over time, oysters were not just used to feed people and produce cash crops for profit. Oyster farmers contributed to an ecosystem within Black neighborhoods by also using oysters as fertilizer in composting methods and by providing jobs for skilled workers and their families.”

Longtime oyster farmer and commercial crabber Ernest McIntosh Sr., who owns the family-operated oyster farm E.L. McIntosh and Son Oyster Company, has been harvesting wild oysters along Georgia’s coastline for more than 50 years.

In an interview with Jolvan Morris, a consultation biologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Oral History Archives, McIntosh described how the oyster industry supports the economies in the Southeast, particularly St. Augustine, Jacksonville, Savannah, Atlanta, and parts of the Carolinas. McIntosh Sr., who taught his son to harvest oysters as a pre-teen, used revenue from crabbing and oysters, as well as a SBA loan, to build a seafood packing and shipping house which provided jobs and income to other members of the community.

Although the crabbing portion of the business proved fruitful for McIntosh Sr., he explained that his brothers left due to shifts in the industry, government regulations, and increased pricing. “They all turned sour at it … and got out,” said McIntosh, whose business is now entirely focused on oyster farming.

A Vanishing Legacy

Around 1929, state governments replaced oyster harvesting with repletion seed programs, hoping to restore oyster beds that had been displaced by large kelp forests. However, decades after the programs were initiated, efforts were thwarted by fungal pandemics and natural predators.

In the 1970s, overharvesting, pollution, and gradual climate change continued the sharp decline in oyster farming, especially in Black communities. And while restoration practices have resulted in boosting previously low oyster populations, Black oyster communities have yet to fully recover, jeopardizing the history and traditions of culturally-nuanced oyster harvesting.

Today, oyster farming is still practiced by the descendants of generations of Black harvesters in coastal communities along the Chesapeake Bay such as Hobson Village, Virginia, where Mary Hill, a seventh-generation oyster harvester may be the only Black woman oyster farmer in the country. Local historians, societies, museums, preservationists, and oral storytellers in Louisiana parishes as well as other once-thriving historically Black oyster communities along the coasts are working to ensure the stories, recipes, and traditions of Black oyster farmers don’t get lost in shifting economic and political landscapes.

Accessibility and Education in Mind

“While it has steadily declined in African American coastal communities, accessibility and education can further support development in oyster farming,” said Jordan Lynch, aquaculturist and farm manager of the Key Allegro Oyster Farm in Rockport, Texas.

Lynch said “one of the biggest hurdles in advancement is visibility and access to capital for underrepresented and Black [oyster] farmers.”

There are, however, organizations like Minorities in Aquaculture which are increasing opportunities for anyone who wants to learn more about oyster farming or any careers in the aquaculture sector. While Minorities in Aquaculture is the currently the only minority workforce development organization in the industry, according to their official website, they are committed to “educating underrepresented demographics about the environmental aquaculture and a growing viable career pipeline.”

Lynch, who is originally from Iowa, knew that in order to get more career-focused information, he was going to need to get out of his hometown. Not only did he leave his construction career to pursue an education in aquaculture at Texas A&M in Galveston, he voluntarily interned with a local oyster farmer who showed him the ropes. “I also paid my way to a lot of national conferences, but I know that everyone can’t always afford to attend them.”

“In order to preserve the legacy, there should also be more education on the nuts and bolts of oyster farming,” said Lynch. “If new oyster farmers are just learning the ropes, they should definitely understand their access to landing and the history of the farm site. How far is the landing from how you’re going to get your oysters? Five miles versus 10 across the bay makes a huge difference. Also, what about the history of the site … how often does the bay close?” he continued. “There’s a ton of research that needs to be done.”

Diverse Storytelling Holds Another Key

“Oyster farming today is pretty much a face-to-face network … and the relationships you build with people in this industry are critical if you want to go far,” said Lynch.

After a delectable first experience eating raw oysters in Charleston, South Carolina, Kamille Harris and Jasmine Hardy highlighted their newfound love by starting an Instagram page, Black Girls & Oysters, where the couple showcase themselves eating and learning about all-things oysters.

“Not having prior knowledge of the intersection of Black history and oysters, I really did not think oysters were eaten widely by people in our communities. So, bridging that gap and helping our people to understand the history, is going to get more Black folks not only wanting to taste them, but potentially even work in oyster farming or seafood commerce,” said Hardy.

Dawson confirmed that, as storytelling evolves, new generations are sharing the stories of Black oyster farmers (past, present, and future) in unconventional ways to ensure visibility.

“Instead of just providing information through scholarly texts and museum exhibits, social media platforms can help historians get information to individuals in short, digestible chunks,” he said.

Jasmine Norton also envisions a future where accessible information can open more doors especially for Black oyster enthusiasts, chefs, scientists, historians, restauranteurs, harvesters, shuckers, dredgers, packagers, transporters, or anyone who wants to explore the oyster industry for its history or as a trade.

“One of my goals is to have my own brand of oysters that are sourced from Chincoteague, Virginia, the birthplace of Thomas Downing. It’s my way of honoring history … And I’m definitely not the only one fighting to keep our connection to oysters alive. Through storytelling, we can make sure our narratives — and our legacies — don’t disappear.“