Farmers are fighting AI companies offering fortunes to build data centers on their land. Can they withstand the pressure — and live to farm another day?

“Life-changing money.” That’s how Wendy Reigel describes the windfall developers are offering farmers for their land, potential sites for hyperscale data centers to meet AI’s massive processing needs. Reigel is a grassroots anti-data-center activist who successfully fought the building of a center just 300 feet from her house in Chesterton, Indiana; she now helps other communities mobilize against data center incursions. She can only make an educated guess as to how much money is on offer — almost everything about these facilities is shrouded in secrecy.

“$20,000 an acre would be low-balling it,” Reigel said. “$40,000 would be maybe a starting point. And I’ve heard as high as $90,000.”

From the Pacific Northwest to the Northeast, communities are seeing a surge of tech-center buildouts as American tech leaders embark upon what Wired magazine called a “battle for AI dominance.” New executive orders from the Trump administration will eventually ease environmental permitting and other barriers to these builds — there have been three such orders since January 2025. And with this wind beneath their sails, AI-giddy companies like Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Oracle have embarked on a national land grab.

Legislators often welcome data centers for their promise of jobs, infrastructure development, and increased tax revenue and property values — rewarding developers with tax breaks and weak regulations. Meanwhile local residents decry them for guzzling water, driving up energy costs, fouling the air, churning out noise pollution, and causing land prices to skyrocket. (In some instances, land prices surpass Reigel’s guesstimates: Developers are paying $150,000 an acre for farmland in Ohio, $400,000 an acre in Utah.)

Some farmers are loath to condemn fellow farmers who sell their land for this purpose. They don’t begrudge life-changing money to anyone who’s contended with their industry’s often brutal fiscal realities, although a farmer in Michigan who sold his land for an “astronomical” sum — in the interest of what he called progress — says his neighbors don’t wave at him anymore. With or without the animus, farmers who opt not to sell are left to contend with the potential destruction of their operations and their lives. “It ruins all our little farms around here that we worked all our lives on,” a couple in Coweta, Oklahoma, told the local news.

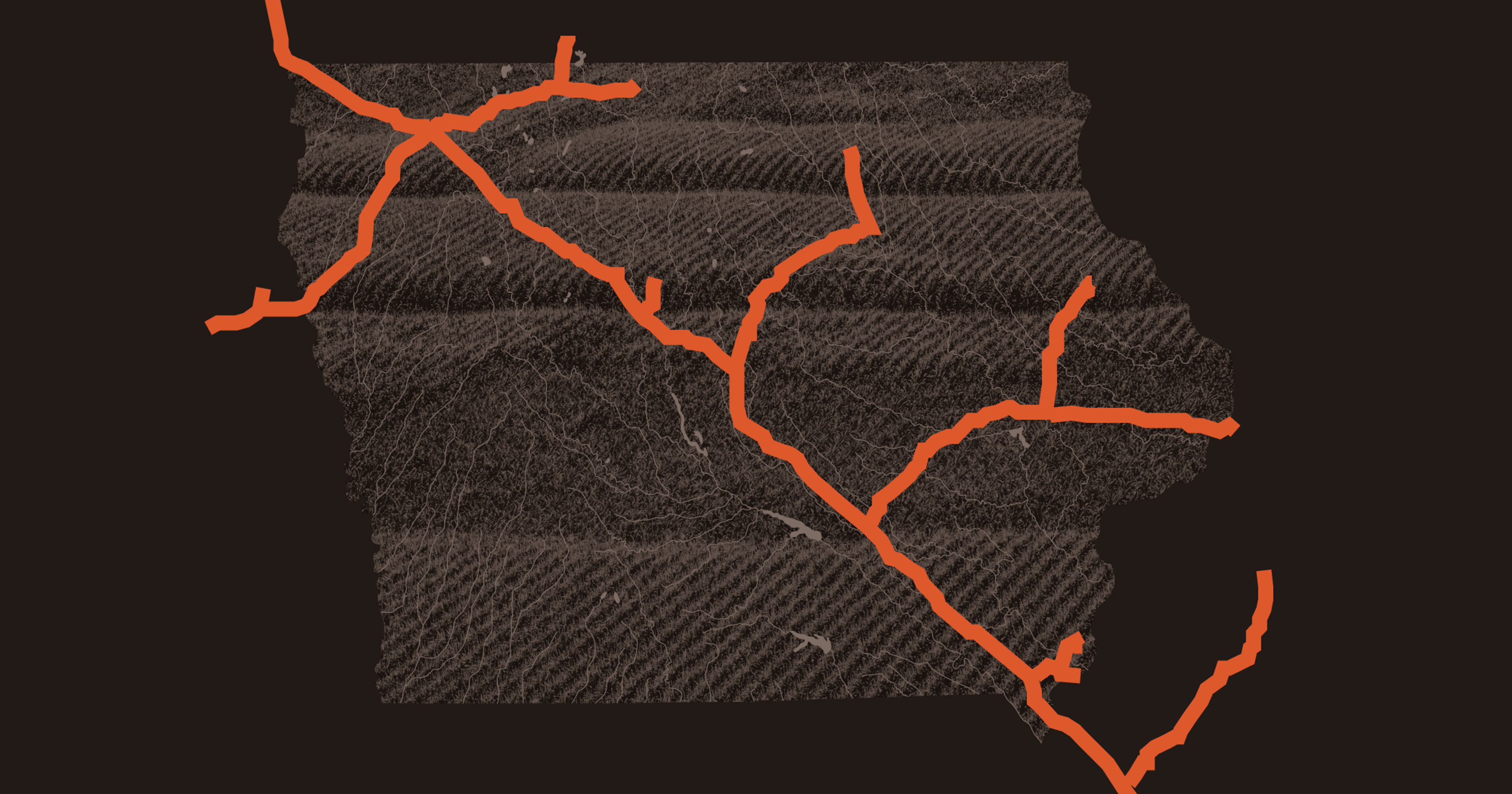

There are data centers popping up almost everywhere, from Oregon and Nevada to Georgia and Virginia. (Loudon County is our country’s “data center alley.”) But Indiana has become an especial target for hyperscale facilities, of which there are an estimated 1,130 globally; since Indiana produces a lot of corn, soy, and hogs, it’s also illustrative of the challenges that farmers in particular are up against.

“It ruins all our little farms around here that we worked all our lives on.”

“Of the 40-something [data centers] that we’re tracking” in the state, “most of them are in ag areas,” said Bryce Gustafson, program organizer for environmental nonprofit Citizens Action Coalition (CAC). He’s not sure what the exact implications are for food security although he noted, “Last I checked, we can’t eat data or AI.”

Even before data center developers started to swarm, farmland in Indiana was going for about $15,000 an acre, according to Kiley Blalock, who married into a third-generation row crop and beef-producing family some 30 miles east of Indianapolis. At first, she said, private equity firms were the eager buyers.

“That hurts us, because they’re paying a higher price than market value for the land; that drives property values up, then farmers are struggling to pay their taxes,” Blalock said. That price is also “completely out of reach” for any farmers starting out or looking to expand their operations. When data centers are willing to quadruple or quintuple an already-inflated price, affordability for farmers goes up in smoke.

Morgan Butler is a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, who helped the tobacco- and dairy-producing community of Pittsylvania County, Virginia, fight off a 1,000-acre AI facility. He said developers are drawn to farmland because “They see a huge area. In their eyes there’s nothing on it, nothing particularly valuable, there aren’t that many residents so hopefully they won’t kick up a firestorm of public opposition.”

That rural “nothingness,” though, is precisely what community members opposed to data centers hope to preserve. One farmer in Kentucky turned down an $8 million offer for his land, citing his family’s sentimental ties to it and the community’s fondness for the landscape as it is. However, one bitter truth for farmers is that much of their net worth can be tied up in their land; retirement might necessitate selling property because they have few or no other assets, making a generous offer for acreage hard to refuse.

“They’re paying a higher price than market value for the land; that drives property values up, then farmers are struggling to pay their taxes.”

Blalock is currently fighting a proposed 585-acre data center that abuts some of her farmland in Henry County. The facility would be built on land sold by the property’s non-farming heirs — no one knows for how much. Many sellers sign NDAs because companies “don’t want them knowing that maybe the next project down the way is getting double,” said CAC’s Gustafson.

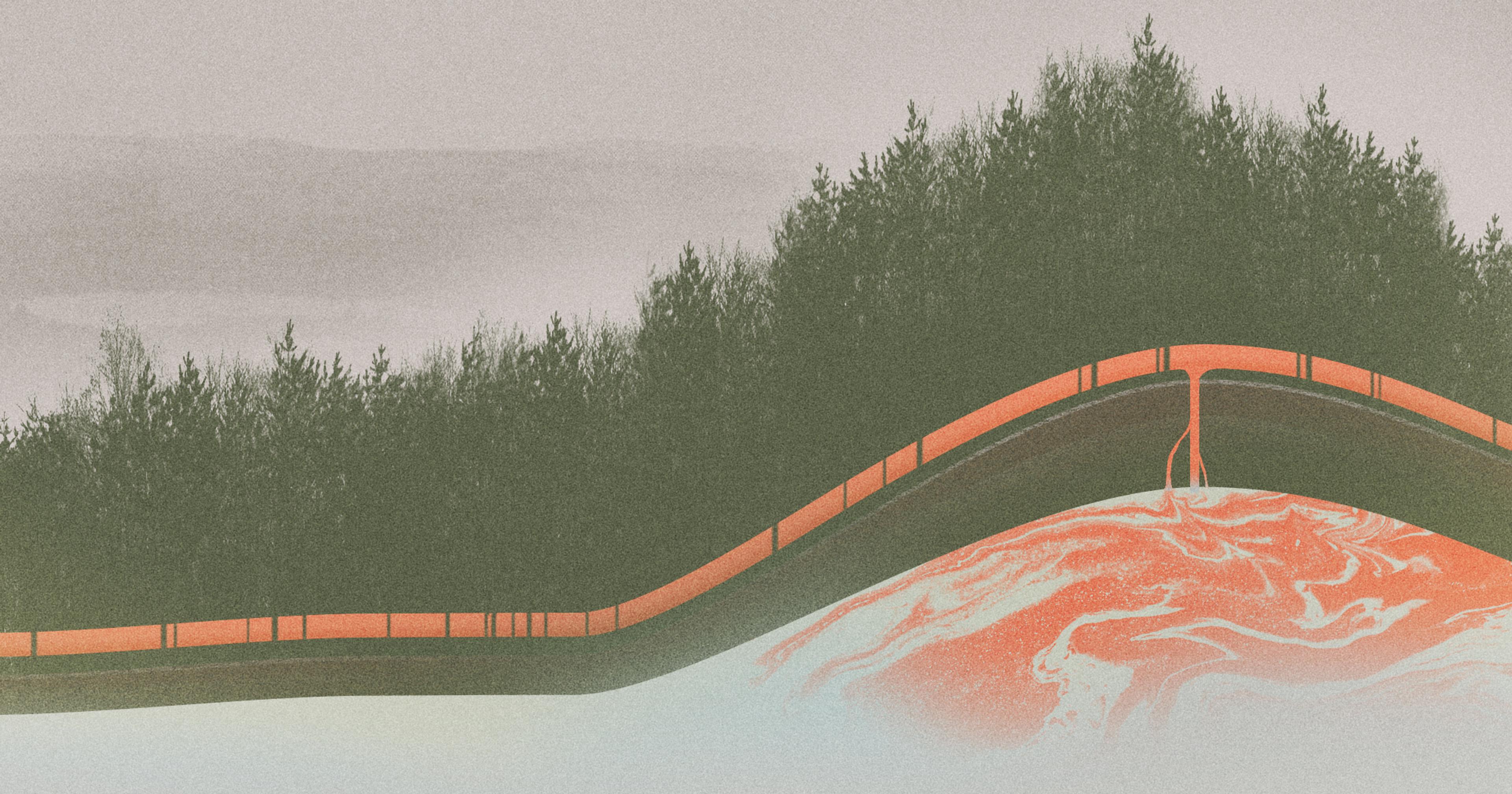

A hyperscale data center can use upwards of 8 million gallons of water per year, mostly for cooling its servers. “We don’t have the water supply” to meet those needs, said farmer Bart Snyder. Snyder lives in Wolcott, an ag-centric town 135 miles northwest of Henry County, where Amazon is scouting a 330-acre facility 1,000 feet from one of his farm properties. He’s suing his town’s commissioner and redevelopment committee members (all of whom signed NDAs) for approving a farm-to-industrial land rezoning on behalf of that facility. “To consume that much water would absolutely devastate our row crops” and potentially create a deficit for Snyder’s 30 beef calves, which each drink 15 gallons of water daily. “People are literally scared to death,” he said.

Blalock is concerned that if a data center is approved in her county, it could deplete the local aquifer, causing neighbors’ wells to run dry and preventing her family from ever drilling one of their own for their cattle. She said that would put them out of business and leave their land valueless. “No one has answers for us about, what’s our backup plan? What if people lose water? You can take your family to go stay in a hotel but it’s not like doggy daycare; you can’t show up with 50 head of cattle.” And she worries: “Are we going to be the generation that loses the farm?”

Farmer anxiety doesn’t end with water use and property values. Data centers require enormous amounts of energy to run — worldwide, they consume 55 gigawatts per year, with 14 percent of that used by AI. They’re projected to gobble 84 gigawatts by 2027, with 27 percent used by AI; for reference, one gigawatt can power 876,000 homes. And they’re driving up the cost of electricity for users who live nearby, by 267 percent a month.

Snyder uses electricity to grind and dispense cattle feed and he doesn’t relish the idea of a price spike if a data center moves in. Even worse, these facilities tend to have emergency generators, for which they store hundreds of thousands of gallons of diesel onsite. What happens if the facility catches fire? In Wolcott, population 952, “The local fire department is all volunteers. We don’t have anything to fight a fire like that,” Snyder said.

“Are we going to be the generation that loses the farm?”

Over in Blalock’s part of the state, developers want to connect the proposed data center to a nearby natural gas pipeline, to generate what she calls “clean-er” energy — Indiana got 42 percent of its energy from coal in 2024. “We’re talking about VOCs [volatile organic compounds] and methane that are going to be released,” she said. “Is that going to create a heat island that’s important to anybody that grows corn?”

Blalock explains: “Night temperatures for corn, they need to drop. That helps with the development of the kernels. If nighttime temperatures remain elevated, it can drop yields up to 10 percent. We have hot summer nights; it’s Mother Nature, she’s her own thing and we can’t control her. But this is manmade.” The data center is in her county’s power to control — but planning commissioners have voted to recommend it, with no environmental review or guarantees the company will be held accountable for much of anything.

There’s also the hum. Data centers “emit low-frequency noise 24/7 through their fans and their diesel generators,” said activist Reigel. Both Snyder and Blalock are quick to point out that no one knows how this affects livestock. “We live out here with grain bins and when we harvest, they have heaters and blowers on them to dry the grain, but they’re only going to run for a few weeks,” Blalock said. “I’ve seen studies that show that even just with fans in barns, that can impact cattle” — elevated noise is connected to lowered milk production, and fertility disorders in bulls. “But again, these are more questions that we have that nobody can answer.”

What’s being offered to communities in lieu of answers are promises — rarely backed up in clear, detailed, contractual writing, say critics. There are promises that an incoming company will pay for infrastructure upgrades, or that water quality and amounts will remain stable, or that economic benefits will pour into rural towns.

SELC’s Butler says that for this reason, his organization is encouraging communities to make sure they’re requiring permitting for data centers — something that’s often bypassed in these transactions. (Permitting currently tends to fall under state and local jurisdiction, although in December of 2025 the House passed a bill that would make federal permitting easier.) Butler would also like to see states offer guidance and legislation to help small communities better understand both the pros and cons of what data centers bring with them.

“The developers say, ‘Oh, we promise we won’t do that. We promise we will do this. We promise, promise, promise, promise.’ But there’s nothing binding them to that,” said Blalock. She scoffs at a developer offering a million dollars to the local school system, although in one Michigan township, a data center will pay an estimated $8.1 million annually in school taxes, which is nothing to sneeze at; it will also pay $14 million for a farmland preservation trust.

Still, Blalock and others remain unconvinced of data centers’ benefits. “The town is thinking in terms of, what is the tax revenue going to be?” she said. “They’re not thinking about, how does this uplift every individual in town? And it doesn’t.”