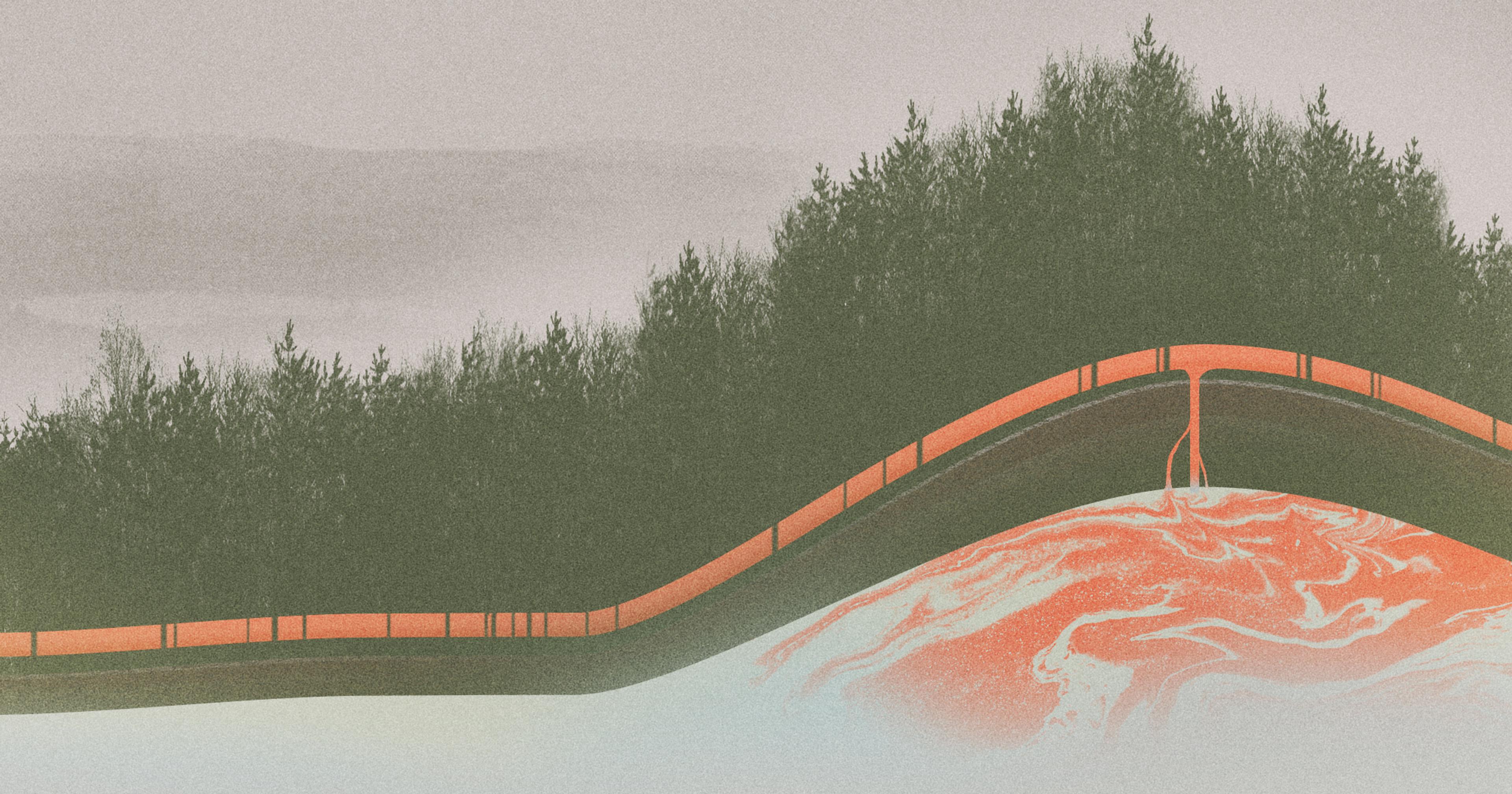

The geology of southern West Virginia leaves its groundwater vulnerable to pollution, making the state’s new natural gas pipeline a risky proposition.

There are some who say the water of Monroe County, West Virginia, is the purest and best-tasting in the world — or at least it was in the 1990s. The springs on Peters Mountain, which straddles the border with Virginia, won first prize at the Berkeley Springs International Water Tasting four times in that decade, beating out — as farmer Maury Johnson will tell you — the renowned municipal water of New York City.

Johnson’s family has owned over 200 acres of farmland in Monroe County for 130 years, in the verdant Hans Creek Valley. Coming around the bend of a two-lane road into the valley, you behold a patchwork of dandelion-dotted pastures where small farmers raise sheep, cattle, pigs, and even a paddock of wide-eyed, statue-still deer. Underneath that farmland is a geological formation called karst, which is found throughout the greater Appalachian region.

It is a layer of ancient limestone, made porous over eons by mineral-laden water and riddled with caverns and underground waterways. Precipitation that falls on mountain ridges makes its way into the valley springs below through subterranean creeks that rise at intervals to catch their breath above ground, moving through the earth like a thread through cloth. In karst land, the earth is thin and porous and filled with gateways to aquifers below. That groundwater, the delicious prize of the county, is easily touched and tainted by pollution.

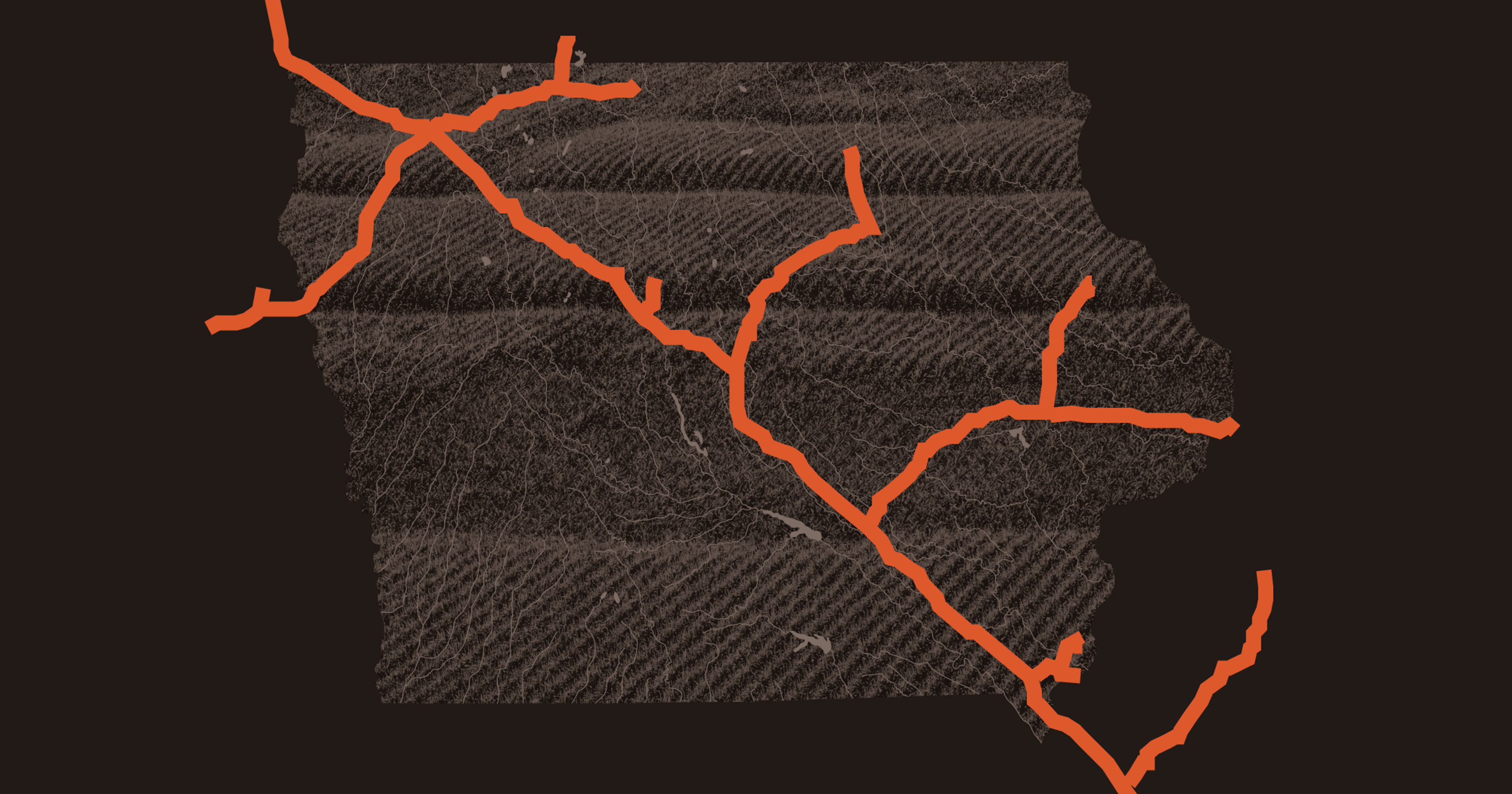

Meanwhile, the Mountain Valley Pipeline is a 303-mile conduit for gas from the Marcellus Shale, and runs from the northern panhandle of West Virginia to a compression facility in southern Virginia. Its six-year construction process — totalling $7.85 billion — has been marred by controversy and delays. It’s faced many legal challenges and significant activist protests.

In June 2023, Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) tied blanket approval of pipeline-related permits to the passage of the Fiscal Responsibility Act, the bill that addressed the national debt ceiling. This month, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) cleared the pipeline for operation, which is expected to begin July 1. (EQT Corporation, the operator of the pipeline, did not respond to requests for comment on this story.)

When pipeline construction began on Johnson’s property in 2018, he monitored the activity very closely, concerned about violations to the organic integrity of his land. Johnson clears less than $5,000 a year selling agricultural products like hay, corn, and pumpkins, which is not enough revenue for him to seek organic certification for his farm. But he’s implemented exclusively organic practices on it since about 1993. That’s when an over-application of fertilizer on the hay fields poured down the mountainside in a heavy rain and into an aquifer via a sinkhole, contaminating the groundwater. “You could taste fertilizer for a month,” he said. “And at that point I decided, no more chemicals on this property.”

Over the course of the pipeline construction, Johnson meticulously documented any violations he saw on his property that would compromise the aquifer that sustains the farm: trucks refueling over streams, for example, or improper protections against erosion. And during that first year, he began to observe an increase in sedimentation in the water from his wells, especially after a rain. In the spring of 2018, he noticed the water would turn white or brown with mud and grit with each rainfall, and in 2021 he stopped using his own well water altogether. He has no running water in his house today.

“They’ve changed the way the water travels across the property,” Johnson said. “Landowners in at least three counties now have water issues — ponds have dried up, wells have dried up, the wells maybe have become unusable.”

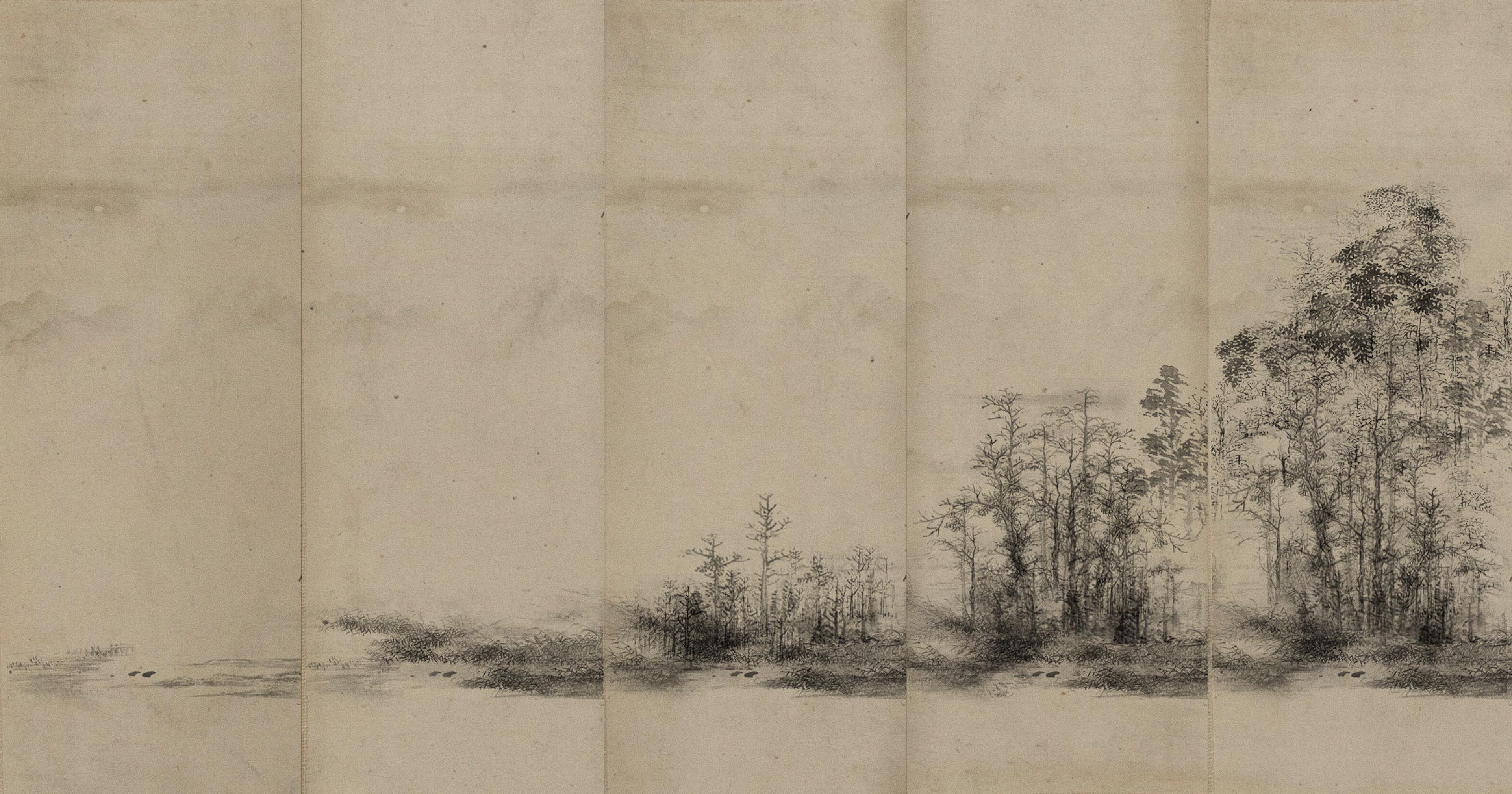

The pipeline crosses Indian Creek in Monroe County, at the site where Maury Johnson was baptized as an adult.

·Eve Andrews

Over the course of this past spring, Johnson has been driving his well-worn minivan across the Greenbrier Valley to meet with other landowners who have experienced issues with their water since the construction began. With the West Virginia Rivers Coalition, he wants to build a body of evidence that the land and water have been altered since the pipeline has been installed. Johnson himself has brought the evidence he’s collected across the region to the attention of FERC, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, Manchin’s office, and the National Organic Standards Board, among many other agencies and government officials. He’s filed about 350 complaints in total.

“A lot of people didn’t know they could complain. They thought: ‘Well, you know, I haven’t heard anybody else having a problem. Maybe it’s just me, maybe it’s something not related,’” Johnson said. “We have to go talk to people and get the data to figure it out. Sometimes things happen and it’s not related to the pipeline, but you got to go out and do some research.”

Since the Mountain Valley Pipeline was first proposed in 2014, community groups, scientists, and environmental advocates have been warning of the potential dangers of building a large natural gas pipeline through the mountains of West Virginia and Virginia.

“It’s true we have tons of pipelines crisscrossing the state of West Virginia, but my research documents the fact that no other pipeline in the country has ever attempted to cross the same amount of high-risk terrain that Mountain Valley Pipeline does, and it’s not even close,” said Jacob Hileman, an environmental science professor at West Virginia University. “We do have techniques for minimizing and mitigating risk in infrastructure projects, but you’re not eliminating that risk.”

One particularly risky aspect of the region’s terrain is the steep mountainsides with highly erodible soil, an issue only aggravated by swift and powerful rains brought on by climate change.

J.R. Gill shows a filter for his well water, which fills completely with sediment every day since his well casing cracked in November.

·Eve Andrews

“When you site a pipeline along an entire ridgeline and remove the trees and disturb the soil, that’s going to impact all of the runoff in the valley below,” said Autumn Crowe, an environmental scientist and executive director of the West Virginia Rivers Coalition. “We’re seeing the runoff increase and the drainage patterns change so that there’s more flooding in areas where there hadn’t been because there were trees and vegetation to soak up the water, and now without that people’s properties are being flooded.”

That flooding can dump contaminants into the karst’s many access points to aquifers. Some residents along the pipeline’s path are also concerned about toxic chemicals like spilled diesel fuel from trucks, or protective coating on the pipe itself, which degrades over time. Underground channels that run through the karst can carry pollution fast and far, potentially miles away in just a few hours.

But the biggest problem so far has been the sediment, which comes from runoff and blasting through rock. It fills stream beds and pours through cracks in karst into groundwater and wells. That can suffocate the wildlife in fragile stream ecosystems, pollute drinking supplies for farm animals, and turn rural water systems unusable.

“The typical protection that people think of when something happens on the land, that it’ll sink down through all these filtering layers of dirt and sand — well, we don’t have that, we’re missing the filtering layers,” said Nancy Bouldin, a resident of Monroe County who has protested and organized against the pipeline. “And it’s a problem because there is no public water service for probably 80 percent or more of the homes in Monroe County that this pipeline goes past.”

Karst is also conducive to sinkholes that cover the land like pockmarks, and can be coaxed open by events like a flood, construction, or the drilling of a well. The Greenbrier Valley, which stretches across three counties along the southeastern edge of the state, has one of the densest concentrations of sinkholes in the world. (The town of Lewisburg sits almost entirely on something called an uvala, a large divot in the earth formed by a compound of sinkholes.) You could say the land is sensitive; it gives way and fractures under sustained pressure.

The Mountain Valley Pipeline, its path visible in the background, runs right behind the Lindside Methodist Church in Lindside.

·Eve Andrews

Johnson spends much of his time now making his rounds across the state, climbing narrow mountain roads to meet people who have lost reliable or clean water supply since construction of the pipeline began. One Sunday in April, he invited me to follow along, and brought me to the home of J.R. Gill.

Gill bought his dream property in Pence Springs, just northeast of where the pipeline crosses the Greenbrier River, in September 2018. He built a house from the ground up with lumber cut from his own trees, and over the years installed heat and electric and plumbing connected to a well accessed by a small pump house.

In November 2023, Gill awoke to a boom that shook the whole house. A crew had resumed pipeline construction less than a mile from his home about a month prior. That night, Gill said, workers were blasting — using explosives to clear a trench for the pipe through rock — and that the sound also startled his neighbor in the next holler over.

“That next morning I got up and I didn’t have any water in the bathroom, so I went out to the pumphouse after it turned daylight and checked my pump,” he said. “And that’s when I seen my concrete floor busted around my well casing.”

That concrete foundation slab, which is eight inches thick, had been cracked and pushed up. The well casing itself was fractured. Its filter comes up filled with mud every day, and there are days when no water comes out of it at all. The pipeline company sent its staff karst specialist to look at the damage, and deemed that there was no way the pipeline construction could have caused it.

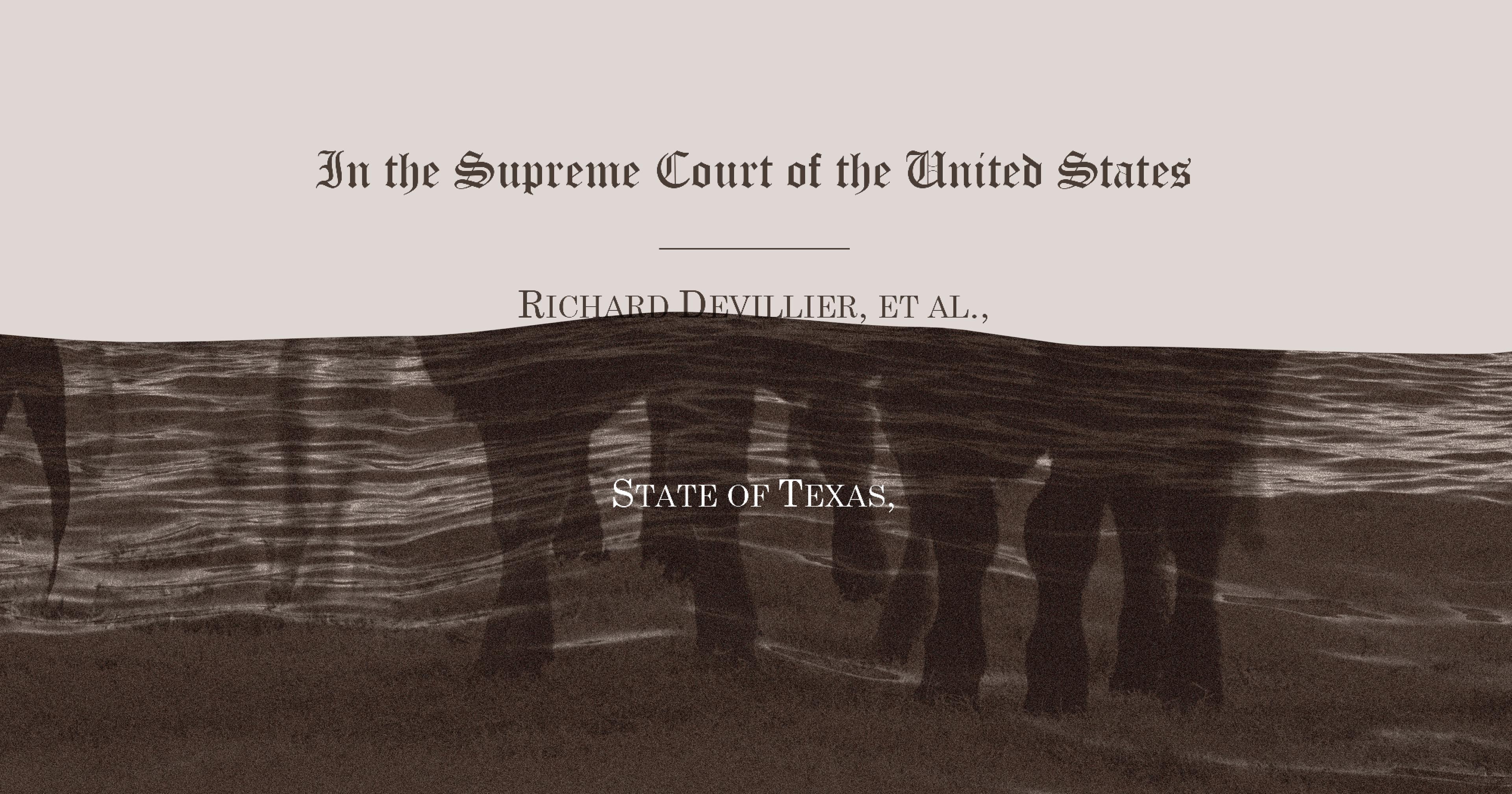

Drilling a new well will cost nearly $10,000. Gill has contacted Manchin’s office, West Virginia Governor Jim Justice’s office, and the Summers County Commissioner’s office. In April, the county commissioner granted him a meeting to document the well problem. From there, he said, that office will bring the issue to the FERC, the governing body that permits pipelines. But FERC exists to get pipelines approved, not to regulate them, and it’s unlikely that Gill will see any money soon — if at all.

Landowners in the Mountain Valley Pipeline’s path are struggling with the classic dictum of economics: Correlation is not causation. They observe changes to their land, water, and animals, and can say they started after pipeline construction began, but they can’t claim with any certainty that the construction is responsible. And what can they anticipate now that the pipeline is actually going into operation?

“The power imbalance we face, unless you can prove 100 percent beyond a shadow of a doubt that MVP caused these damages, you don’t have any recourse as a landowner to be compensated,” said Hileman. “It’s not enough to just say this has never been a problem in the past but now it is, and that’s unfortunate.”

Becky Crabtree, who owns a farm right next to the pipeline’s path crossing Peters Mountain, said that last year all but two ewes in her flock died, and the surviving ones appear to be barren. Last spring, all of the lambs were stillborn. She’s waiting for the results of water testing of their wells and ponds, in hopes of getting some answers.

“The death of so many sheep was as heart-breaking as it was mysterious,” she wrote in an email. “We may never know [what caused it], but are not going to keep sheep any more.”