This year’s devastating Crabapple Fire revealed ranchland vulnerabilities — and provided a roadmap for how to minimize future damage.

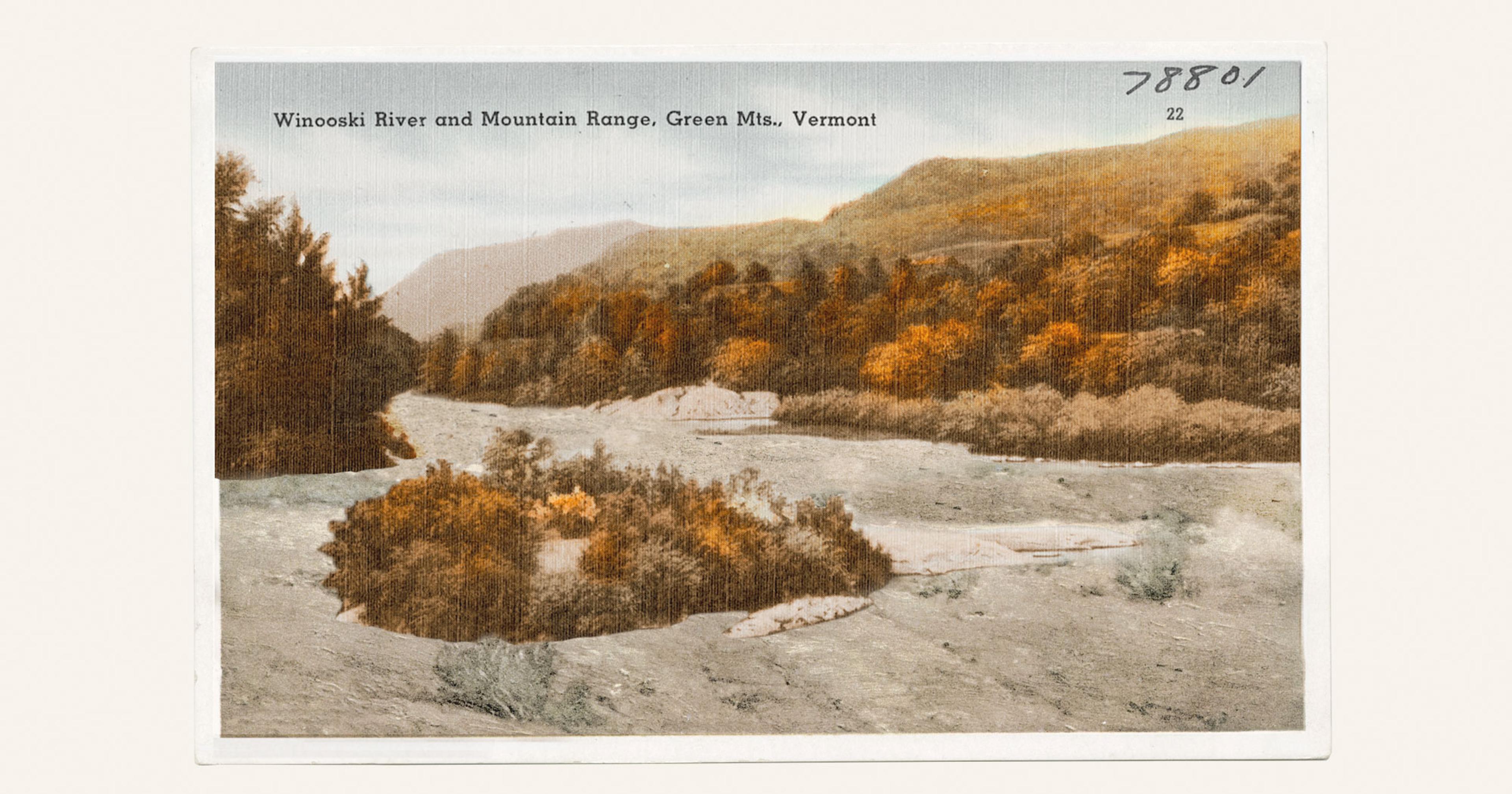

Rolling hills covered in tall grass, short trees and shrubs, and wildflowers every color of the rainbow — it doesn’t get much more picturesque than Texas Hill Country in the spring. Late March is when the wildflowers are in full bloom, lining the highway alongside ranches, vineyards, BBQ halls, resort spas, and other tourist attractions.

This year, just before peak wildflower season, nearly 10,000 acres of Hill Country burned in a scorching wildfire — later named the Crabapple Fire for its origins on Lower Crabapple Road.

“It literally just took off and we could not catch it,” said Fredericksburg Fire Chief Lynn Bizzell, who spearheaded containment of the Crabapple Fire. He said in his nearly 50 years of fighting fires, this one stood out as especially overwhelming — calling the heat “incinerating,” and noting that this fire moved quickly, making it particularly hard for his crew to catch.

The vegetation across the land was a huge part of what made this fire high-speed and hot — including tall grass and cedar trees. Both of these are endemic to Texas Hill Country; however, grazing animals typically keep these two types of kindling in-check. With more people moving to Hill Country and managing their land without grazing animals or prescribed burns, kindling like this is becoming more plentiful — which means wildfire risk will continue to rise.

Unless — we fight fire with fire.

*

Tom Proch didn’t lose his home to the Crabapple Fire, but he did lose his guesthouse, woodworking shop, barns, shed, chicken coop, trailers, and around 40 acres of trees and timber. In terms of land management, Proch does his best to keep his recreational land clear of fire kindling — keeping in mind the cost associated with managing that much recreational land.

“Long story short, if you have the equipment, all it takes is time to manage the land,” Proch said. “But if you don’t have the equipment, it takes time and a bunch of money.”

And Proch is not alone. Many landowners in Hill Country now file for wildlife exemption for their non-agricultural land, a way of paying agriculture property taxes in return for performing conservation practices. Managing that land can pose a challenge when it comes to minimizing wildfire kindling.

“To me, a lot of the country now is undergrazed, and that’s why our fire danger has skyrocketed around here.”

“Because there’s portions of the land here under wildlife exemption that are not grazed, the cedar that grows in there has the fuel around it, the grass, to be very, very volatile,” said Brad Roeder, county extension agent. “To me, a lot of the country now is undergrazed, and that’s why our fire danger has skyrocketed around here.”

While it may seem simple (less kindling = less chance for a wildfire to spread), in practice this quickly gets into the weeds of land management — literally and figuratively.

*

Cedar was key to the Crabapple Fire burning hot, due to the high oil content of these trees and the tall grass growing around them on land that hadn’t been grazed. Under more humid conditions, sometimes cedar can actually work as a firebreak — due to their high leaf moisture potential.

When the fire broke out, the humidity was down to 9%, according to Fredericksburg Prescribed Burn Association (PBA) president Allen Ersch.

“At 20% humidity, if you have short grass burning you can spray it out with water, look back at it, and it’s burning again,” said Ersch. “Like a trick candle — you blow it out, and it comes back. At 9% humidity, you’re lucky to get it out the first time.”

Ersch has worked with fire in a productive way for Texas Hill Country for over 20 years, serving the community as a certified private prescribed burn manager, and teaching landowners how to use prescribed burns and brush pile burns to manage their land. He also uses prescribed burning to manage the nearly 600 acres of property he currently manages for himself and for others.

“At 20% humidity, if you have short grass burning you can spray it out with water, look back at it, and it’s burning again. At 9% humidity, you’re lucky to get it out the first time.”

Looking at the history of the land, Ersch pointed out that fire has always been a part of the story, but how people have interacted with and viewed fire has changed significantly.

Prior to European settlers moving in, Texas Hill Country was open land with frequent wildfires that would start from campfires and lightning strikes and would burn until they were stopped by natural breaks like creeks. However, German influence brought fences around property owned by different families to contain grazing animals like cattle and goats, and fires needed to be put out so they wouldn’t destroy those fences.

Overgrazing quickly became a large and consistent issue.

“Tall grass was wasted grass,” Roeder said. “The first picture of our ranch was from the drought of the 50s, and there is literally not a blade of grass anywhere in sight.”

When people started turning away from the land for their livelihood after the 1950s Texas Drought, the grass had time to recover — and so did the cedar, previously kept in check by goats.

*

In 1995, Texas enacted a wildlife management exemption from high property tax — this alternative to farm exemptions meant people could own large pieces of Texas land without paying high property taxes, and without having to graze animals or plant crops. As Ersch put it, many landowners opted not to have the “pleasant remains” left by cattle on their land under wildlife exemption. Put simply: Land without cattle is land without cattle manure, too.

Morgan Treadwell, professor and extension range specialist at Texas A&M University, said that both a fear of fire and of overgrazing has kept landowners from preventing wildfires — especially those who are managing land under wildlife exemption.

“They’re sort of in preservation mode, a little bit of let-nature-exist-in-a-vacuum type of thing,” she said. “But when you start talking about the natural processes that shape plant communities throughout the Edwards Plateau, Hill Country, the panhandle, all of that — they crave fire and grazing. They cannot survive without it.”

She explained that oftentimes landowners who move out to Hill Country from larger towns or cities don’t prepare their land for things like floods and fires, even though they are both real threats to this part of Texas. “It’s another example of humans becoming even more disconnected, and rather than living in sync with Mother Nature, they’re just fighting it,” she said.

When it comes to managing brush to prevent wildfires, there appears to be two options for wildlife exempt plots and rangeland alike — graze it or burn it.

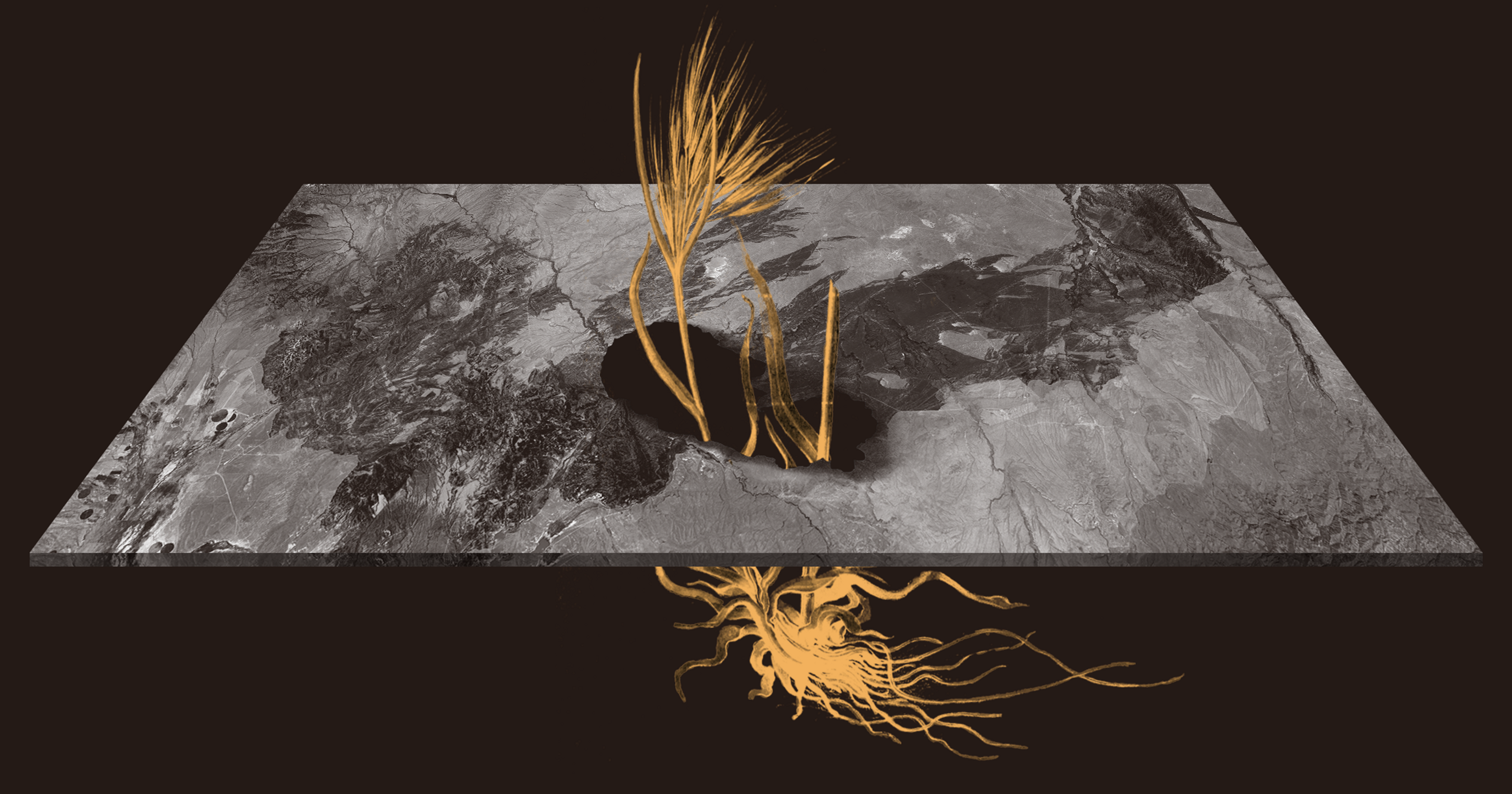

Treadwell also made the point that fire is not only a native to Texas Hill Country, but it also plays a crucial role in maintaining soil health and plant biodiversity that conservationists and ranchers both depend on.

“If I can graze it, I can burn it, and then I can graze it again — it’s a really cool cycle that inevitably benefits [ranchers’] bottom line.”

“I think there’s lots of reasons why we should look to inject fire into every place that evolved with fire — after that reset, it’s incredible the amount of diversity that’s released on every trophic level,” said Treadwell.

Although many people who run cattle on their land have an incredible understanding of what it takes to keep their grass healthy, many really “put the brakes on” — as Treadwell put it — when it comes to fire. “Few producers really embody that synergistic process of the more you burn, the more grass you have, the more brush and trees you suppress, and the less they are choking your grasses out,” she said. “If I can graze it, I can burn it, and then I can graze it again — it’s a really cool cycle that inevitably benefits their bottom line.”

And she would know — her family is the fifth generation on their ranch just north of Hill Country, where they’ve been using a combination of prescribed fire and grazing to manage their land for decades.

So while the number of wildfires per year has steadily risen, in Texas and across the United States, a fear of fire might only fuel the ones that are out of our control.

Conservation of Texas grasslands may call for lighter grazing than in decades past, but swinging the pendulum in the opposite direction makes the land unmanaged — perfect kindling for an unmanageable wildfire when the conditions arise. Striking a balance between prescribed burning, grazing, and giving the land time to rest between management styles is what will likely move Texas ranching, conservation, and wildfire prevention forward more than any one of these alone.