Louisiana crawfish farmers took a massive loss from drought this year. As climate change continues to disrupt the industry, will they be able to adapt?

Tucked inland of the Gulf of Mexico and a stone’s throw from the Tabasco hot sauce factory in South Louisiana, Vermillion Parish is crawfish and rice country. Adler Stelly, a farmer in the parish, operates approximately 3,000 acres of crawfish and rice fields — a symbiotic pair of crops — with his brother. All told, it’s the staggering equivalent to 3,000 football fields, or 1,200 full city blocks.

Read Next

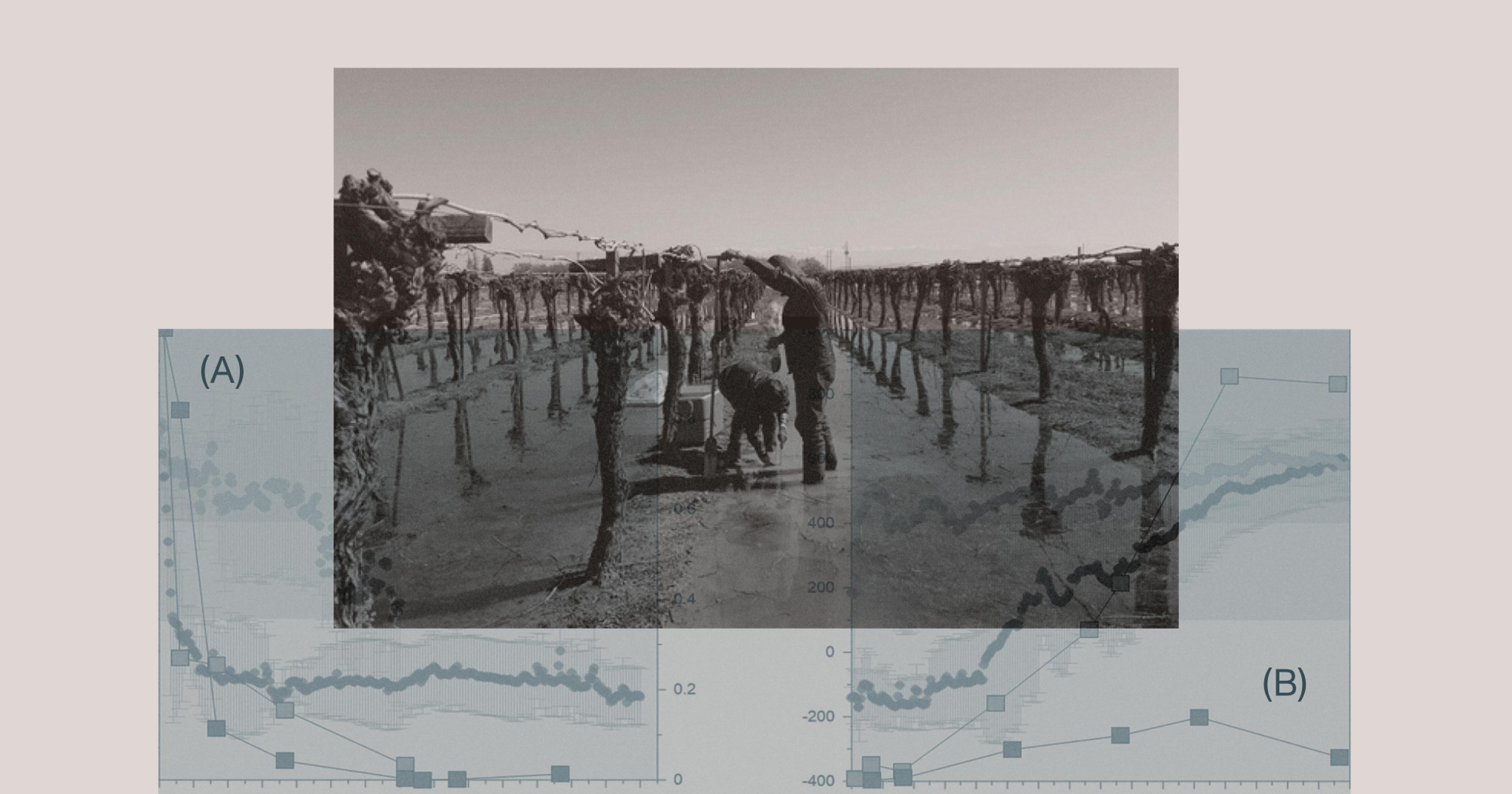

Farmland flooding could help with both extreme weather and depleted aquifers. But will it contaminate drinking water?

After a crippling drought, California has enough water to grow rice this year. Its troubles aren’t over.

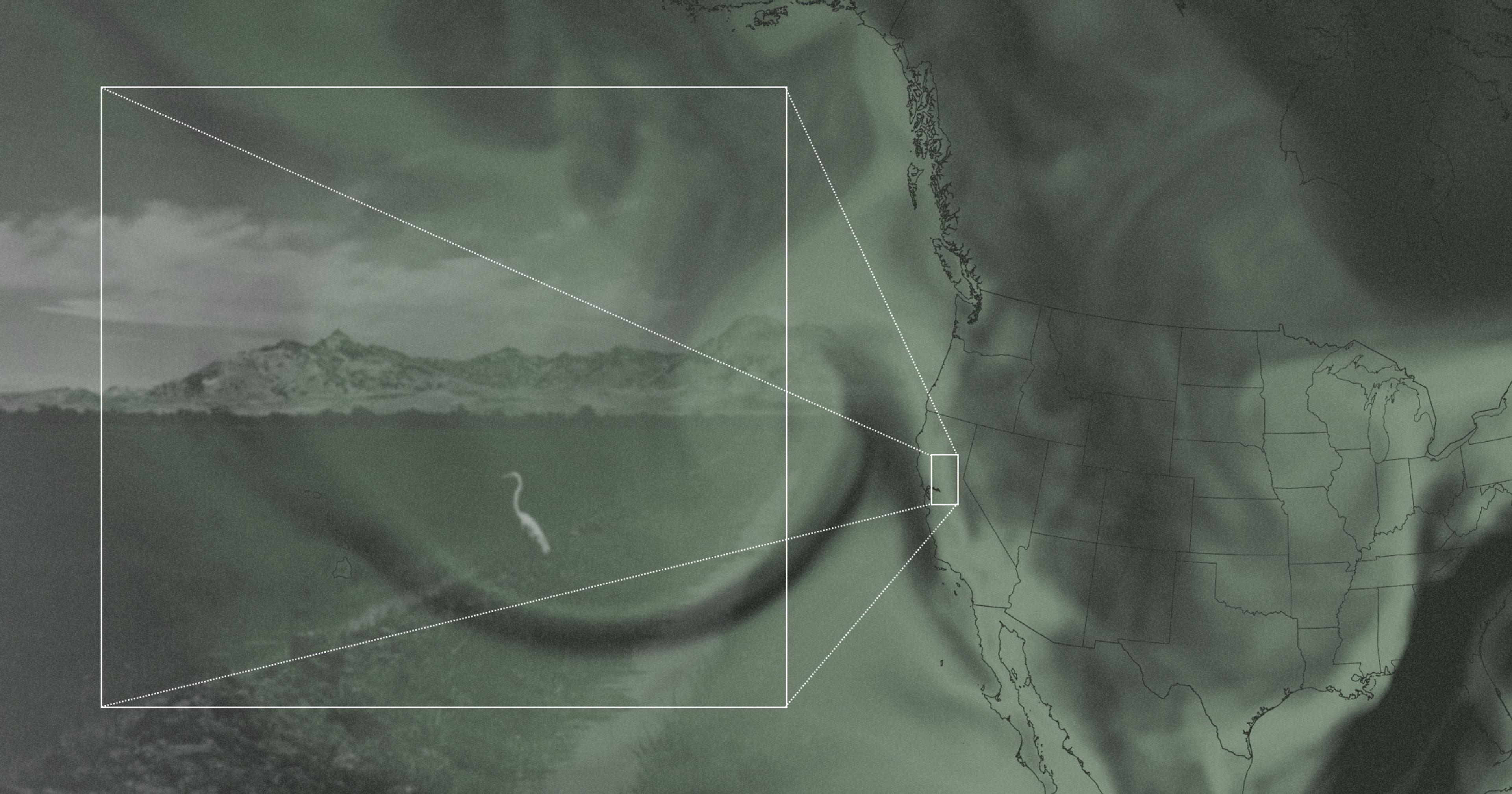

One of the World’s Strangest — and Most Critical — Fisheries Is in Serious Danger

Normally, the abundance of crawfish throughout the parish means that the price can drift as high as $3.50 and as low as $1 a pound throughout the season. But over the past year, virtually every single acre of Stelly’s land was impacted by last summer’s historic drought, which torpedoed crawfish availability and caused available crawfish to double and triple in price.

In an area where farmers can expect to yield 450 pounds of crawfish per acre, that monumental loss reverberated. For Stelly, it meant that from late November to mid-June, traditionally crawfish harvesting season, a local workforce wasn’t employed. Agricultural farmworkers from Mexico could not come north for seasonal work. Many, many acres did not produce any crawfish at all.

“A lot of these crawfish died in the drought when they were buried up in the off-season,” he said. “It’s a part of their life cycle, and how they reproduce. The ground dried up entirely too much, which dried up their hole. So a lot of those crawfish died in the ground, and I never saw them at all.”

Due to the impact of a quarter-billion dollar industry going nearly belly-up in the first quarter of the year, the Louisiana Commissioner of Agriculture and Forestry, Mike Strain, issued a request in February for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to provide monetary relief to crawfish farmers. By March, the governor followed suit with a disaster declaration.

Strain said that about 100,000 acres of crawfish production were lost throughout the state due to the drought, nearly one-third of the 320 to 340 thousand acres dispersed across the state. A drought of that magnitude, he said, hadn’t occurred since 1942, and before that, 1924.

The stakes are getting even higher as average daily temperatures, especially throughout the summertime, continue to break national and global records. As the fourth-hottest state in the country, politicians, researchers, and farmers themselves are eyeing the sky across South Louisiana, trying to determine the best ways to bounce back not just from this past drought, but the next that may be right around the corner.

The Managed Ecosystem

There are two types of crawfish in Louisiana that only deviate based on how they’re harvested: wild-caught and farm-raised. Wild-caught crawfish are the domain of fisherman who, similar to crabbers, take off into the Atchafalaya Basin and drop traps into deeper waters than the managed rice fields. From there, they report their yield to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. According to estimates by the Louisiana State University (LSU) AgCenter, wild-caught crawfish constitute just 20% of the state’s crawfish industry.

Todd Fontenot, an LSU Extension agent, said that the farm-raised crawfish crop starts, at the core, with rice. The two crops are symbiotic because the timeline of flooding, draining, and harvesting rice fields coincides with the ebbs and flows of crawfish production. In the wild, crawfish grow without the presence of rice. But to manage a harvest, the crops are complementary.

“Once the rice is growing and has an irrigation flood on it, which means the irrigation water is at a good depth and the rice plants are growing strong, it’s late April or May, and these rice fields are intended for crawfish production in late fall and into the spring,” Fontenot said.

In springtime, crawfish are seeded into growing rice crops in watery, flooded fields lined with mud levees. In Stelly’s case, many fields are covered by wide roofs to protect workers from rain and heat as they stomp through the mud in rubber boots and gloves. The fields are drained in the summertime and harvested for their rice. In the meantime, crawfish burrow into the mud levees along the perimeters of the field. They stay underground until October when the fields are flooded again and all of a sudden, they’re rife with the crawfish that dug out of their mud burrows and are fished from around November into June.

Some crawfish farmers opt to let the fields rest for a year in between crawfish crops while others alternate between two working fields. Another option is maintaining a permanent crawfish field, which requires seeding rice back into the fields as soon as farmers curb crawfish harvesting in early spring.

“[If you’re seeding] 200 pounds of crawfish per acre that are $2.30 a pound, that’s a heavy investment for that farmer to make, not knowing the weather conditions in the future.”

No matter the format, many farmers opt to supplement their crawfish fields with seed, or more live crawfish, to ensure there’s a healthy stock in the coming season. Seeding crawfish can be done in one of two ways: Mudbugs can be raised in a holding pond nearby and introduced into flooded rice fields, or live crawfish can be bought on the market and used as seed.

“The intention of stocking improves production by far,” Stelly said. “We were trying to [seed this spring], but with the shortage of crawfish and higher prices, we didn’t get out what we wanted to get out,” he says. “Farmers are putting in everything they can get their hands on and afford at the same time.”

Stelly cited another major cost that cropped up in the past year: water. Since his fields did not receive adequate rainfall and many areas with flooded surface water dried up, he had to pump in more groundwater to make up the difference — it still wasn’t enough. What were supposed to be humid, flooded fields dried up, which killed all of the crawfish that burrowed because the mud was far too brittle for them to crawl back out.

But experts still don’t know if the massive crawfish shortage stemmed from them trying to crawl out of their burrows and failing to do so. Another theory, Fontenot said, is that crawfish could have stayed in their burrow longer than normal because without good, soaking rain or flooding the fields in lieu of it, crawfish don’t know exactly when to exit hibernation. In such a situation, crawfish will eat their young to survive since their eggs continue hatching, even while they’re in their burrow.

“It all depends on the weather from here on,” said Fontenot. In the case that the weather takes a turn away from wet, soaking summer rains, he said that farmers are going to have to try a few tactics to prepare for the future.

Preventing Disaster

One option farmers can utilize in the coming years to recover their crawfish is simple: stock heavier. The downside is that this requires a gamble because it’s expensive, and a risk against the weather.

“[If you’re seeding] 200 pounds of crawfish per acre that are $2.30 a pound, that’s a heavy investment for that farmer to make, not knowing the weather conditions in the future,” Strain said.

Another option is to flush crawfish ponds with extra water to keep them very moist and deeper than usual, but the problem with that is that crawfish may emerge from their burrows too early if the ponds are soaked too much. It’s also extremely expensive if a farm isn’t located near an abundant freshwater source.

“You don’t want crawfish emerging in late August and September, even if the [rice] fields are harvested,” said Fontenot. “[If you] flush or wet the fields, [crawfish can] emerge too soon and not be able to survive … We’re concerned. We’re definitely concerned.”

Another type of disaster that Fontenot sees with overseeding crawfish is an overabundance of product in the next year or two. While that may seem like good news and indicate market recovery, it also means that prices for crawfish stock will fall, and ultimately hurt farmers.

“Farmers are putting in everything they can get their hands on and afford at the same time.”

“If we end up with too much crawfish, that causes depressed prices,” he said. “Right now, [I fear that] more than the weather situation.”

From Ag Commissioner Strain’s perspective, the number one move that crawfish farmers must make to become more sustainable and resilient in the years ahead, no matter drought or heat, is making sure that fields are adjacent to an aquifer with plenty of fresh — not salt — water.

“If you don’t have freshwater or are in an area where the aquifer is depleted, you may not be able to raise crawfish there,” he said. The cost of flooding the fields in an emergency, he added, is enormous if there is not a natural source of water nearby. Over time, fields that are far from natural water sources may need to be shuttered.

Strain isn’t concerned about prices falling from too much local crawfish on the market, but he does worry about the importation of crawfish from China that occurs when local supply cannot meet demand.

Even so, he is optimistic. Even if farmers may have to be flexible and shift some crawfish ponds in the coming years due to a lack of water, he doesn’t see the combination of rice and crawfish failing on a long-term basis.

“We’re in a transition phase,” Strain concluded.