Consumers went crazy for dry beans during the pandemic. Now, a group of Cornell researchers wants to help more farmers cash in on the trendy crop.

Once relegated to the back of the pantry, dry beans are back in a big way — and farmers want in on the craze.

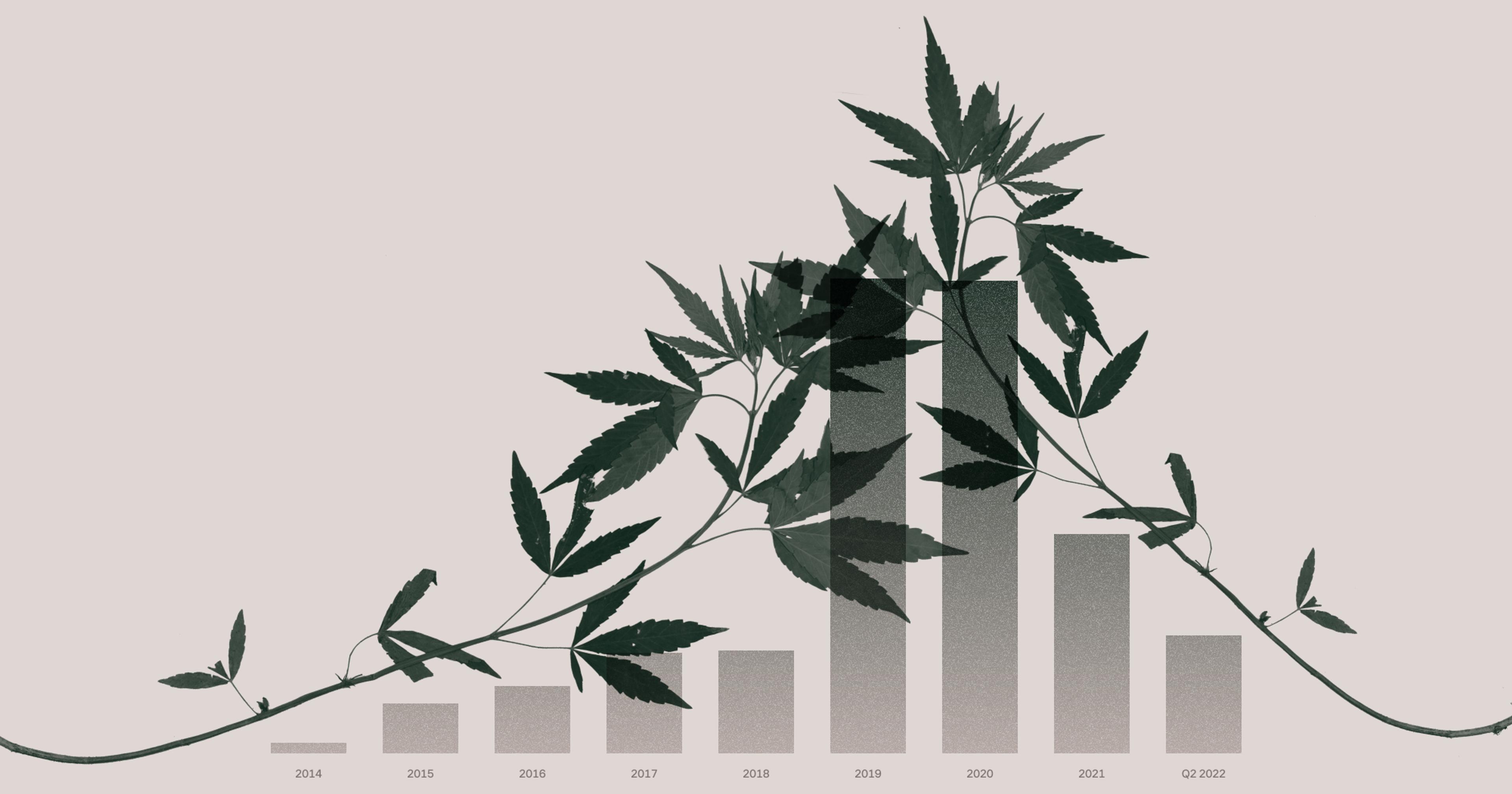

The chaotic availability of food during the pandemic, coupled with a growing interest in plant-based nutrition and home cooking, helped boost bean sales by as much as 400 percent in 2020. But even before the novel coronavirus started making headlines that March, causing people to panic-purchase shelf-stable grocery staples like beans, flour, and yeast, consumers were revealing a budding obsession with the humble legume.

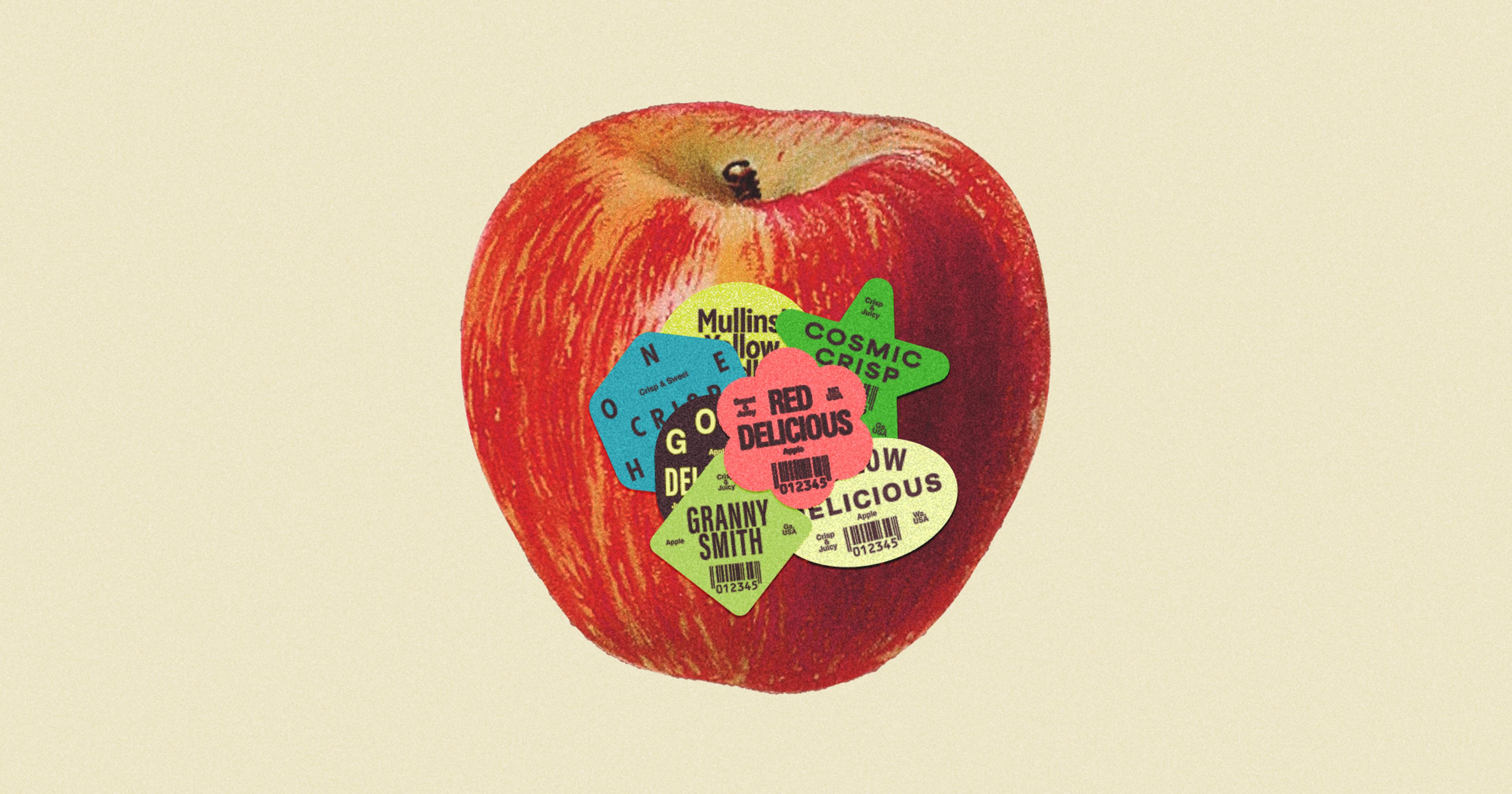

It’s impossible to talk about the American dry bean revival without mentioning Rancho Gordo. Since launching in 2001, the Napa-based company has played a pivotal role in leading a revival of interest in heirloom bean varieties such as Rio Zape, Ayocote Blanco, and Mayocoba — going from selling 200 pounds of beans in 2003 to more than half a million in 2018. People wait years for a coveted spot in the Rancho Gordo Bean Club, a curated quarterly shipment of dry heirloom beans grown in Central California, Oregon, Washington, and New Mexico.

Now, researchers are working to help farmers in other regions capitalize on the big bean boom. As rising fuel prices continue to affect the cost of transporting goods, building localized supply chains is not just important, it’s necessary. If the dry bean yield in North Dakota significantly drops due to drought or other weather conditions — as it did in 2021 — researchers want to build a broad, resilient range of sources. Plus, farmers are always seeking out more valuable crops to add to their rotation.

Bolstering the local bean economy in Northeastern states like New York, Vermont, and Maine is the focus of a new $3 million bean project led by Cornell University. As recently as 1965, nearly half the dry beans produced in the United States came from central Michigan and western New York, where the first ration of dry beans for retail sale in the U.S. were sold in 1836. These days, the Empire State plays but a minor role in the bean industry, producing an estimated 2% of the nation’s dry edible bean crop.

North Dakota currently leads the way in dry bean production, followed by Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Idaho. The large majority of beans grown in those states are farmed conventionally, according to the project’s lead researcher Sarah Pethybridge, associate professor of plant pathology and plant microbe biology at Cornell AgriTech. “Whereas the niche market in the Northeast seems to be organic [demand] driving production,” she said.

Over the next four years, Pethybridge will lead a team of researchers who aim to build a sustainable organic dry bean industry in the Northeast and upper Midwest, where citydwellers are hungry for local bean sources. “There’s a general push toward increasing the frequency of pulses and legumes within people’s diets, and especially towards more of the heirloom varieties,” said Pethybridge. Similar to the heirloom tomato craze, heirloom beans are beloved for their rich flavor and texture, which devotees argue are superior to their mass-produced cousins. “You’re seeing a lot of organic dry beans at farmers’ markets, which we didn’t really see several years ago,” Pethybridge said.

“The biggest challenge that organic bean producers deal with is weed management.”

Beyond the excited bean crowds at the farmers’ market, researchers are excited about the potential for pulses (a category that includes chickpeas, lentils, dry peas and beans) in urban school cafeterias. Starting July 1 of this year, New York City agencies are required to have at least one serving of plant-based entrees per week. “The [city] wants to source a lot of their protein locally and organically, so there’s certainly market opportunities for organic dry bean growers that are close to those big city institutional locations,” said Pethybridge.

Before they can meet that demand, farmers must first overcome a host of challenges. When the Cornell researchers surveyed growers, 72% of them expressed an interest in increasing their production of dry beans but lacked proven strategies to effectively manage disease and environmental stresses.

“Certainly the biggest challenge that organic bean producers deal with is weed management,” said farmer and plant breeder Kristen Loria, who grows half a dozen different varieties of dry beans every year in Danby, New York. Most conventional bean growers rely heavily on soil tillage, turning over the soil mechanically, to manage weeds and diseases. But a major goal of the Cornell research project is to drastically reduce tillage in dry bean production in an effort to boost soil health.

Another major issue for farmers is the multi-step harvesting process most bean varieties require. “Harvesting dry beans, in general, is trickier than with some other crops,” said Loria. “[It] requires special equipment and more knowledge to be successful.”

“Harvesting dry beans is trickier than some other crops. It requires special equipment and more knowledge.”

The traditional two-step bean harvesting process involves an involved process of pulling and windrowing plants prior to combining. “You cut them off at the base, then you put them in a pile to dry on the field, and then come back with a combine to separate the plant residues from the dry beans,” explained Pethybridge. That requires a lot of time and labor — something prospective bean growers might not have a lot of.

To overcome those hurdles, the Cornell researchers are focused on breeding bean varieties that can be directly harvested by a single pass through the field with a combine. “That’s going to be a major factor in influencing the profitability of organic dry bean production,” said Pethybridge.

If the biggest challenges can be mitigated, the future for Northeastern bean growers looks bright. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index, the price of dried beans has steadily grown over the last 25 years. At the end of 2022, the average price (including organic and non-organic) was $1.70 per pound, up from $0.67 per pound during the same time in 1995. When you consider the nearly 3 billion pounds of edible beans the U.S. grew last year, that profit difference is impactful to farmers.

Farmers like Loria are committed to reviving New York’s storied bean industry. In 2021, she and two other growers joined together to launch a local bean collective called Buttermilk Bean, which, similar to Rancho Gordo, showcases a diverse array of dry beans in a seasonal bean club — except these are all organically grown in the Finger Lakes. (Two years after launching, there are now five farmers growing beans for the club.) In addition to marketing their product together, the self-proclaimed group of “bean nerds” shares equipment, too, helping to lower each other’s barrier to entry.

“There is such an amazing history of bean-growing in the Northeast,” said Loria. “It’s something that we lost a lot of, so rebuilding all of those nodes is something we have to do largely from scratch.”