The Ukraine-driven spike in wheat prices comes on the heels of major supply chain disruptions.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has driven a global spike in wheat prices, both in futures and regular markets. However, global food prices were already trending upward, driven by the omni-crisis of COVID-19, drought, and a resultant cascade in supply chain issues. Even in the unlikely event of a quick resolution to the war in Ukraine, the background factors that drove wheat prices up will continue to shape global and American markets.

One way to assess these global background factors is to look at the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) tracking of food prices pre-Ukraine crisis. This data source tracks the aggregate food price index based on all the other food indices, so it’s useful for getting an overall sense where food prices globally are headed.

Founded in 1945 under the United Nations (UN), the FAO manages the UN’s agriculture-related initiatives to reduce hunger and increase global agricultural productivity, including teaching farmers about soil productivity and dealing with the impacts of desertification. To track global food prices, the FAO maintains indices that track a basket of food prices such as cereal, vegetable oil, dairy, meat, and sugar. These prices are aggregated into a master food price index, with each part weighted slightly differently. To actually construct the indices, the FAO tracks multiple prices for a given commodity, and uses a Laspeyres index with the set of collected prices to construct a new index for a given year. To track if prices go up or down, the FAO sets a “base year” price of 100 for comparison with the current year.

The price of wheat has skyrocketed from supply chain issues and drought driven by climate change. In 2020, the price index for wheat was 103.1. In 2021, it jumped to 131.1, a 27% increase.

Increases in the price of food in the U.S. have become a major political issue, with new records in food inflation at home driving consumer frustration. In December 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) tracked a 6.3% yearly increase in prices. But the problem has largely been driven by global adjustments to COVID-19. The FAO tracked a South Korean food price increase from 103.39 in January 2021 to 109.10 in January 2022. In India, food inflation rose 4.05% in December 2021.

In the U.S., the BLS and the Department of Agriculture (USDA) both measure food prices. These food price baskets are created from data collected on families and households, which are then aggregated and weighed based on importance. Sub-indices based on the data collected are created for categories from residency in a rural or urban area, to specific population groups.

Food prices were already spiking globally for multiple interconnected reasons. Increases in oil prices make it more expensive to produce food, leading to costs being passed directly to the consumer via increased food costs. Despite high prices, farmers are concerned about their bottom line; in a February 14-18 poll from the CME Group and Purdue University, 47% of farmers polled said high input costs were their biggest worry. Droughts, including in wheat-growing areas of Russia, are contributing to an increase in food prices as well.

In the United States, wheat prices skyrocketed as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has sharply constricted supply. The invasion poses a global problem because of the EU’s heavy reliance on Ukrainian food production; in 2020, Ukraine was the fourth largest supplier of food to Europe. Prices will likely continue to spike as the war continues.

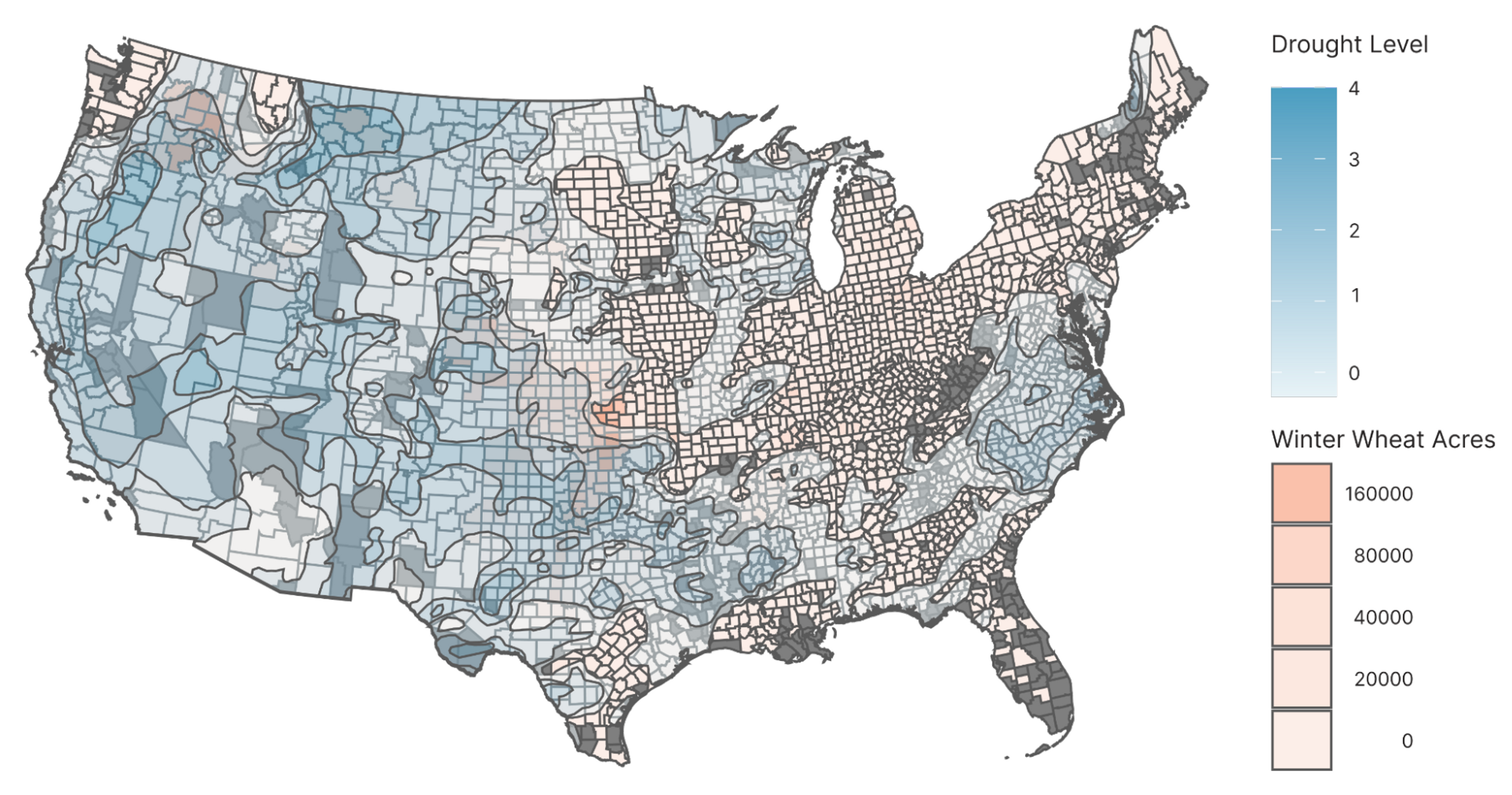

But even before the war, drought and COVID-19 effects were driving prices up. At the end of 2021, severe droughts and pests caused a poor harvest in spring wheat. It did not help that the cost of various goods to produce wheat, such as fertilizer, have gone up as well over the past decade. The most recent spring wheat planting had record lows in bushels harvested. A 2022 USDA report notes that drought is currently affecting wheat production in the United States: American wheat exports have reached a six-year low and a near-record low due to droughts in the Northern Plains and Pacific Northwest.

American wheat supply isn’t going to suddenly collapse; the United States exported some 810 million bushels of wheat for 2021/2022. But 2021 was the second lowest year for total American wheat exports since the 1970’s. 55% of spring wheat, including 78% of Durum wheat in 2020, was farmed in a region with drought.

The increasing global volatility in food prices mirrors what happened during the 2008 financial crisis, when food costs only went up in tandem with global increases in unemployment. Since all major food groups except sugar tracked by the FAO face price increases, it is challenging for consumers to reduce food spending by engaging in consumption substitution. As COVID-19 recedes and supply chains stabilize, prices should slowly come down. But this latest bout of food inflation tells us that our globalized food price regime is quite unstable, and consumers will feel pain in their wallets for some time yet.