As wine regions grapple with labor shortages, rising temperatures, wildfires, and drought, some winemakers are betting on a future that’s dependent on smart technology. Others are less convinced.

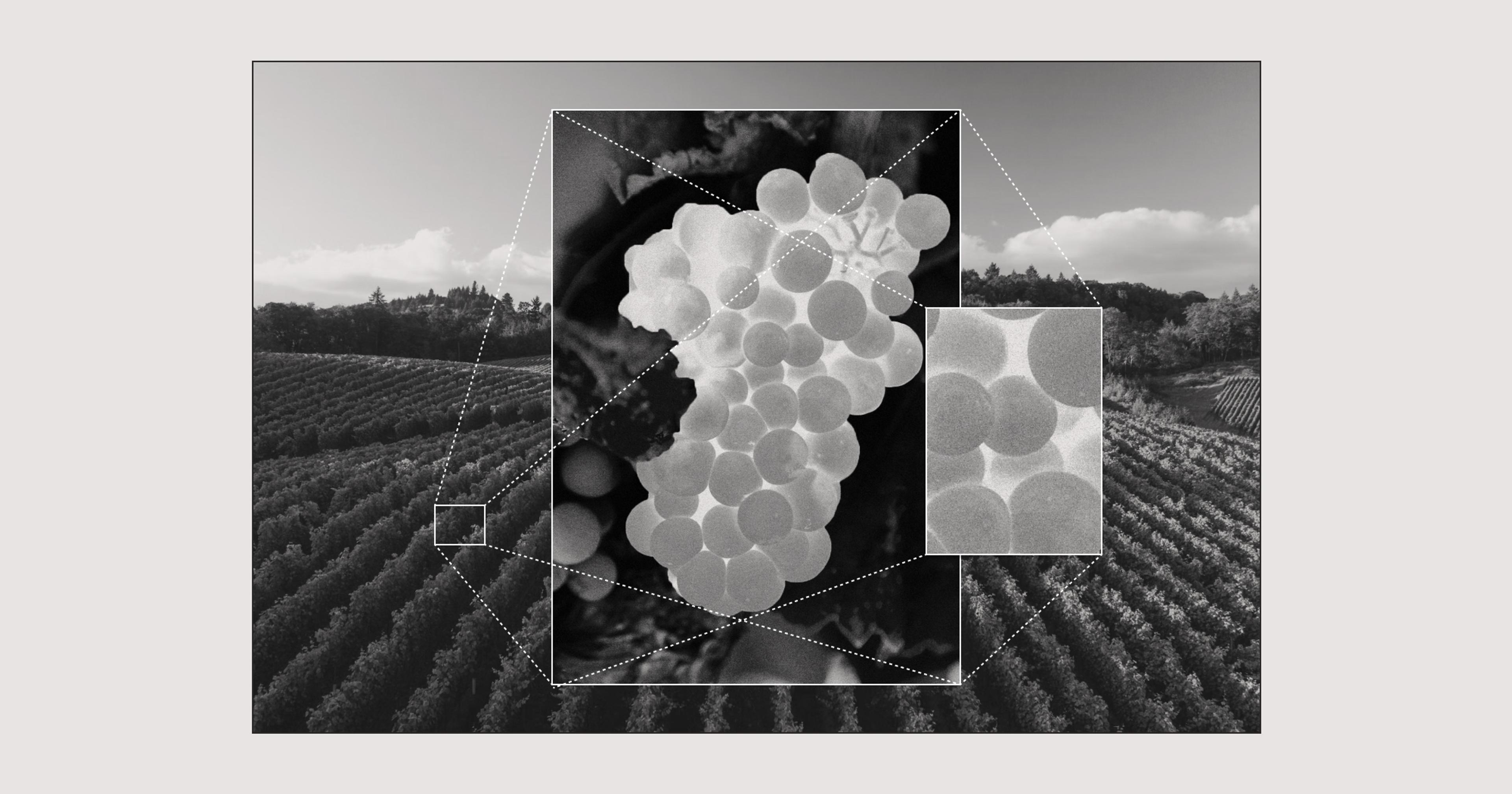

Many people have a romantic ideal of how wine is made. Perhaps they’ve visited a winery for an afternoon tasting, where they’ve gazed out upon lush vines planted on picturesque slopes, sipping pensively from their glassware. If they came during harvest season, they might have seen a crew of workers handpicking the grapes, gently tossing the bunches into bins to be carted off to the winery for pressing.

It’s an idyllic image, and one that you’re likely to witness at many vineyards around the world — for now, that is. As renowned wine regions such as California’s Napa Valley and Oregon’s Willamette Valley continue to grapple with mounting labor shortages, rising temperatures, extreme drought, and wildfire, many wineries are counting on the latest advancements in technology to modernize this centuries-old industry.

Compared to other crops, the stakes are especially high for wine grapes, the highest value fruit crop in the U.S. This crop is high reward, but high risk — unlike corn, wheat, or soybeans, grapes are not subsidized. If there’s a bad year, such as when a late frost kills all the grapevine’s buds, or wildfire wipes out an entire vineyard, that year’s grapes could be a total loss. Even if crop insurance — which is growing increasingly more expensive — covers the cost of the grapes, it means that no wine gets made that year.

In California, where 85% of American wine is made, there are a total of 4,795 producers, covering nearly 90,000 acres of vineyards. The Golden State’s wine industry generates more than $88 billion per year in total economic activity, according to a recent economic impact study from the National Association of American Wineries. It is also responsible for more than 513,000 jobs across many sectors: farming, banking, packaging, and transportation. And when you consider a bottle of Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon sells for anywhere between $75 and $5,000, it’s easy to see how much wineries have to lose if they don’t adapt to modern challenges.

After all, most oenophiles won’t find a robot grape harvester romantic.

Wineries have long relied on some elements of technology to make great wine, such as tank sensors to provide real-time data for oxygen, temperature measurements, and brix (the sugar content of a liquid solution). This has helped winemakers refine their fermentations, improve a wine’s aromas, flavors and textures, and get a better grasp on its aging potential. This sort of technology, once new and novel, is arguably what helped put the U.S. on the global wine map. But while wine production technology has been embraced, normalized even, vineyard practices have been slower to modernize — after all, most oenophiles won’t find a robot grape harvester romantic.

“As farmers have done for centuries, the work was about walking your vines, and looking at your canopies and seeing what blocks need water, what the soil looks like, what is happening based on what you could see,” said Chris Kajani, winemaker and general manager of Napa’s Bouchaine Vineyards.

Now, vintners are finally recognizing that A.I. and modern hardware can be helpful when dealing with the effects of climate change, labor shortages, and other challenges. But installing all that new technology requires a big investment — one that some wineries aren’t sure will ever pay off.

Vineyard Precision

Despite being resilient and robust perennials, grapevines can be finicky creatures, especially in a warming climate. They grow best in soil that has good ventilation and drainage, but the soil must also have good water retention. They like environments with a large temperature difference between day and night, which is when they accumulate nutrients. They need enough sun to produce the right levels of acid, sugar, and pH, but not so much that they burn and shrivel into raisins. When those levels are just right, it’s time for harvest, the moment that winemakers and grape growers patiently await each year, making daily vineyard visits in the leadup to harvest — and sometimes multiple times a day — to taste and run analysis on the berries. Pick too soon, or too late, and that decision can have a cascading effect on the quality of the wine.

To assist these delicate plants on their journey, a host of players has been busy researching and unveiling new agricultural innovation. Much of the progress is being made in wine regions in and around the Bay Area, the epicenter of tech innovation and experimentation. Ambitious startups and established technology giants alike are working to develop products that meet the needs of grape growers and wineries, who contend with a unique set of challenges that differ from other agricultural sectors.

“The ability to put data behind all the things that we were already looking at, but literally just looking at it with our eyeballs — it’s been a really wild ride.”

The industry has seen many advancements in grape-harvesting machines, which do a much better job of picking grapes than in the past, and with less damage to the vines. And to better understand their vineyards through data, wineries are installing weather stations, soil moisture and temperature sensors, and flying drones with infrared technology to get a sense of how healthy their vines are (the more red, the more drought-stressed they are). This has helped viticulturists significantly cut down on irrigation, especially in drought-ridden regions in the West.

During the 2020 pandemic lockdown, Bouchaine Vineyards began working with Cisco — the tech company known best for its computer networking products — to create virtual tasting experiences. At the time, Cisco’s IoT division was rolling out new weather sensors and asked Bouchaine if they could use their vineyards “as a sort of living lab,” said Kajani. She welcomed experimental equipment that would measure temperature, humidity, wind speed, and soil moisture in the 87 acres of vineyards she oversees. “The ability to put data behind all the things that we were already looking at, but literally just looking at it with our eyeballs — it’s been a really wild ride.”

Part of what made the new system so appealing was having access to a dashboard that digests and stores all the data gathered from multiple sites and vintages, which can be accessed from any location — not just while Kajani or her team stood in the vineyard. “It’s going to continue to upgrade our grape-growing and what we decide to do based on what Mother Nature throws at you year-to-year,” she said. Winemakers having such rich records of data could someday come in handy if and when they decide to sell their vineyards — which is happening more now than ever before.

Beyond John Deere

Tom Gamble, a third-generation farmer and proprietor of Gamble Family Vineyards in Oakville, California, who has witnessed Napa Valley’s decades-long transformation into a prestige winegrowing region, believes that tech will be key to Napa’s future success. He’s especially excited for what may be the buzziest toy in wine country right now, which is neither a drone nor a robot. It’s the Monarch Tractor, an electric, self-driving tractor that’s equipped with geofencing technology and an array of sensors and cameras that monitor each vine as it moves through the rows, looking for leaf discoloration or other damage, which can be signs of ill health or a pest infestation.

“It’s going to be able to tell you that there’s something up that you can’t see yet on a vine-by-vine basis. That could be super important for vine health reasons, such as detecting a virus or bacterial infection going through the vineyard so you can get on top of it,” said Gamble. “And just like in people, early detection is always better.”

Last year, John Deere announced the release of the first fully autonomous version of its 8R tractor. But the company focused mostly on equipment that would benefit row crops, which make up the majority of America’s farm acreage. Unfortunately, the size and width of John Deere’s 8R tractor is no match for narrow vine rows. Monarch Tractor’s MK-V model, on the other hand, was designed with the wine industry in mind. It’s smaller than your typical Deere tractor (so it can fit down those narrow vine rows) but larger than a driveable lawn mower. It’s also more affordable — $68,000 compared to John Deere’s starting price of $272,000 for its autonomous tractor.

“How can I afford to not do this? We’ve got to replace tractors all the time. So we’ll do this, and we’ll live and learn.”

“I fully expect it to be like the iPhone 1.0. There’s going to be updated versions, but going electric is going to be super important,” said Gamble, who’s excited to order one when the time comes. “How can I afford to not do this? We’ve got to replace tractors all the time. So we’ll do this, and we’ll live and learn.”

There’s only one problem: Autonomous tractors are currently banned in California. In June, California’s Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board ruled against the use of driver-optional tractors. Critics of Monarch’s driverless tractor say the company has yet to prove that they’re safe enough to be operated without a human operator.

That hasn’t stopped Monarch from testing their pilot series at Wente Vineyards and Crocker & Starr Winery under a temporary experimental license. The company has also been taking orders from some of the largest wine companies in the world, including Constellation Brands, which plans to put the tractors to work in one of California’s most esteemed vineyards. “It’s often that the bigger companies are the first adopters of labor-saving technology,” said Gamble. Earlier this month, as the first production units of the Monarch Tractor MK-V model rolled off the assembly line at the company’s headquarters in Livermore, California, the company was still petitioning to update the state’s agricultural equipment regulations.

Outside Napa

It might seem like younger, less-established wine regions — such as Virginia, New Jersey, and the Finger Lakes in New York — would rely more heavily on technology to catch up to their bigger, more established counterparts. But as Mike Beneduce, winemaker and vineyard manager at Beneduce Vineyards in Pittstown, New Jersey, points out: “Most of the vineyards on the East Coast are too small-scale to benefit from some of the more prevalent A.I. and automated technologies. The price point on some of that stuff is hard to justify unless you’re managing like 1,000 acres.” Instead, it’s the larger conglomerates out West that have more to lose if they don’t take advantage of all technology has to offer them, and more to gain if they do.

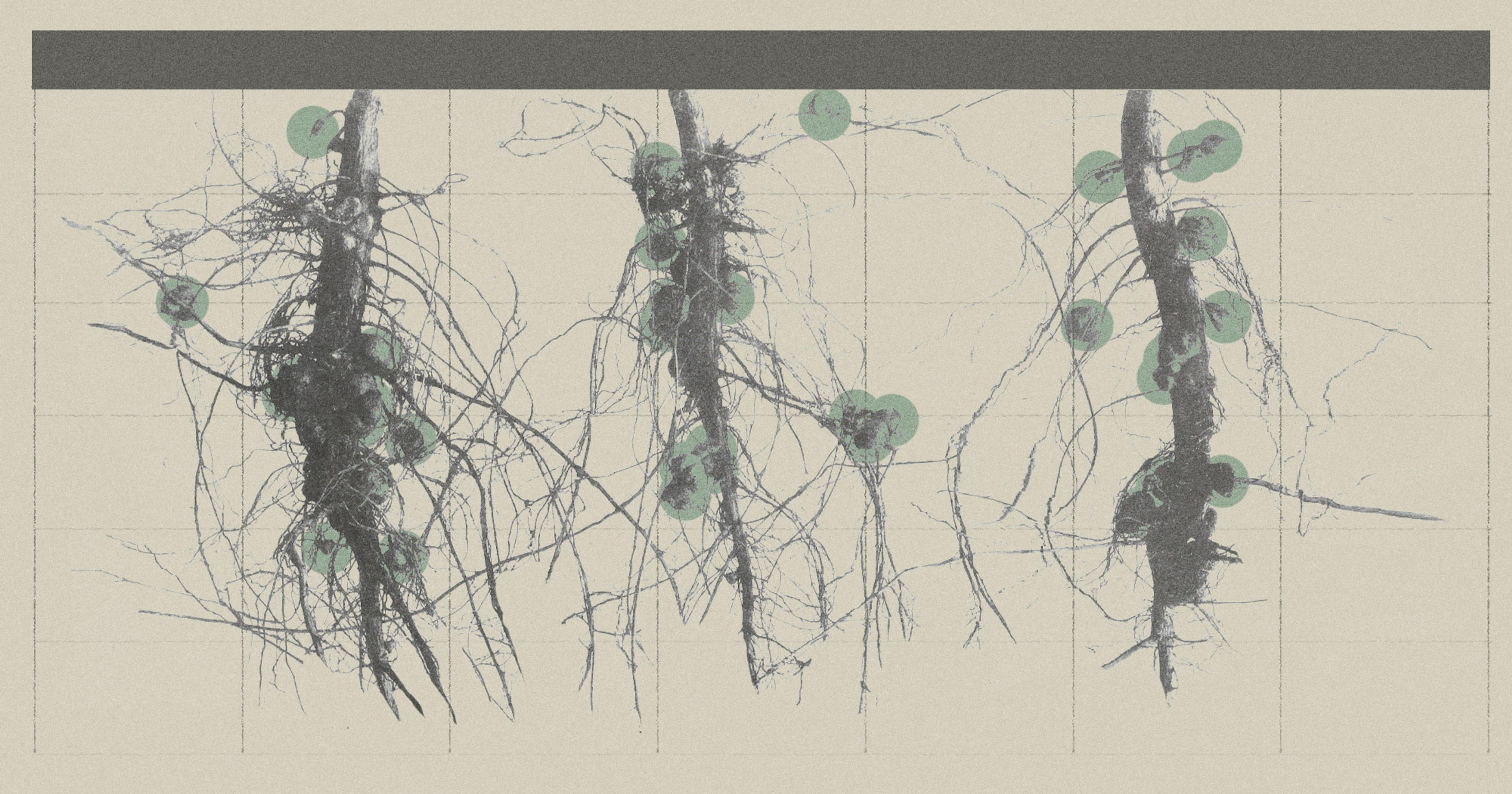

That hasn’t kept researchers from seeing how robots and A.I. can help vineyards in other parts of the country. A new project led by Cornell researchers aims to combine plant pathology, computer vision, A.I., and robotics to help New York grape growers better understand their vineyards and modernize their agriculture practices. Applied roboticist Yu Jiang is in the process of developing an autonomous robot that can roll through vineyards, using cameras and sensors to evaluate the vines, leaf by leaf. That data would then be used to detect grapevine diseases, determine ways to reduce their applications of fungicides, and help develop new cultivars. “The whole purpose is that we want to reduce the use of any chemicals so that we can provide both economic and environmental benefits,” said Jiang.

“The price point on some of that stuff is hard to justify unless you’re managing like 1,000 acres.”

The rise of automation in agriculture has fed into worries over robots and computers taking our jobs. But we’re not there yet. When Jiang brought his robot to Fox Run Vineyards in New York’s Finger Lakes region, co-owner Scott Osborn wanted to believe in its potential. But he found it wasn’t built to operate in his region’s rocky terrain. “The equipment may work on a beautifully trimmed smooth vineyard in California, but once you get into the reality of most vineyards in the U.S., the equipment is not effective,” he said.

So is technology going to be the great salvation for wine grape growers? It depends on who you ask.

“Technology is a tool to improve your craft,” said Gamble. “So far, there’s no all-in-one Swiss Army knife app that does everything … and I don’t think there’s anything that replaces walking the vineyard, but with data, your experience and judgment can make even more informed decisions.”

Kajani, who installed more Cisco monitoring systems after the experimentation phase ended, sees it as simply another important tool in her winemaking toolbox. “Technology is incredibly helpful. It’s not going to replace a person, but that doesn’t mean it’s not insanely helpful,” said Kajani.

Beneduce is less convinced. “Time will tell. My sense is that some of the technologies will be a good fit for our industry and others won’t,” he said. “It’s pretty hard to beat an experienced grower that spends a lot of time in the vineyard.”