On a frigid, remote island that used to import 100% of its fresh vegetables, one American chef set out to keep it local.

Just over 800 miles from the North Pole lies the world’s northernmost settlement, the town of Longyearbyen on the Svalbard archipelago. With average summer temperatures of 3 to 7 degrees Celsius, and more than three months of complete darkness, surrounded by freezing fjords and glaciers, the town is not what most people would think of as hospitable.

None of Longyearbyen’s 2,000 residents was born there — they include researchers, scientists, adventurers, chefs, miners, students, expert trekkers, businesspeople, and others from more than 50 nations who traveled to this remote Norwegian outpost in search of adventure and an extraordinary life. Most people spend an average of seven years in Longyearbyen before moving on.

Situated on Spitsbergen, the largest island on the archipelago, about 900 km (559 miles) north of Norway in the Arctic Ocean, Longyearben gets about four months of complete sunlight and four months of total darkness. The harsh climate and periods of irregular sunshine make traditional agriculture all-but-impossible. Almost 100% of the food in Longyearbyen is imported, and costs about 20% more than food on the mainland.

“The imported food we get in Longyearbyen is not such good quality and we see a lot of rotten vegetables in supermarkets.”

“The imported food we get in Longyearbyen is not such good quality and we see a lot of rotten vegetables in supermarkets,” said Polina Wilmann, a Russian native who spent two years living in Longyearbyen in the years before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Flying goods into the Arctic is an expensive proposition — and one that leaves behind a huge carbon footprint. If Longyearbyen were a country, it would top the list of CO₂ emissions per capita, with emissions higher than Qatar.

Classically trained American chef Benjamin Vidmar, who lived in Longyearbyen for around 13 years, first moved to Svalbard in 2008, when he got a job as a chef at the Radisson Blu Polar Hotel. He soon realized that the quality of produce and other ingredients — all brought in from mainland Norway, potentially after being shipped there from other parts of the globe — weren’t up to his standards.

“We would pay a lot of money but the imported stuff wasn’t very high quality, and a lot of it would go bad before it got to us,” said Vidmar.

Growing Food on Svalbard

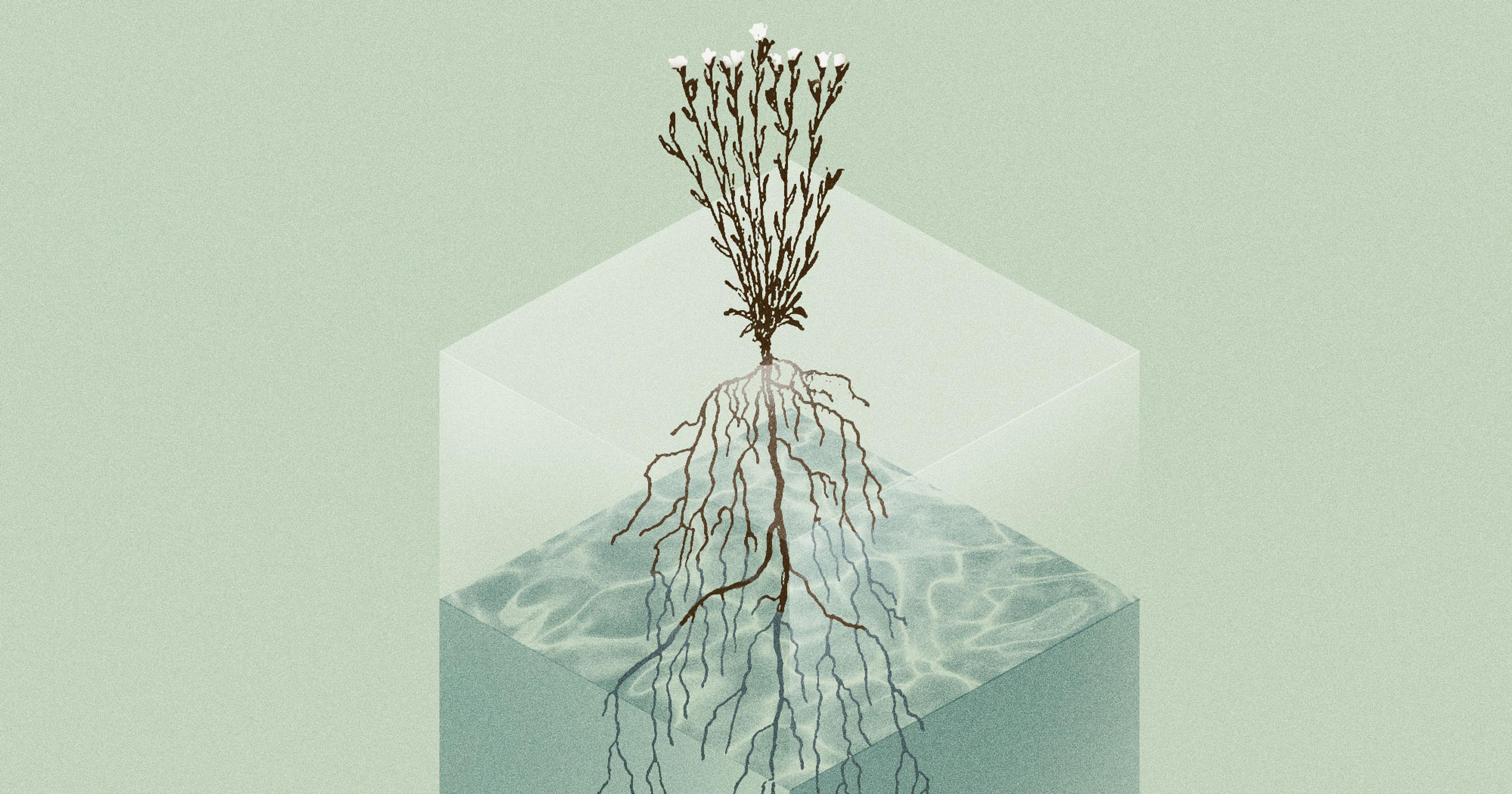

At the base of Plateau Mountain, one of Longyearbyen’s most popular hikes, Vidmar set up the town’s first and only “farm” — a purple greenhouse dome, about 100 square feet in area. This was where he grew tomatoes, cucumbers, potatoes, lettuce, herbs, leafy greens, microgreens, edible flowers, and mushrooms, at various points, to supply to the town’s restaurants and supermarket. Supplementing this was an indoor lab where he used a controlled temperature, along with imported seeds, soil, and fertilizer, to grow a variety of fresh produce and greens.

Seeds were first sprouted in the indoor lab facilities with the support of LED lighting and aquaponics, and eventually moved to the greenhouse. During winter, spanning those many months of constant darkness, most of the greens would remain indoors in the lab.

“It was super-challenging to operate in winter because in Svalbard they have three months of total darkness. So you have to use a lot of energy to try and heat [the greenhouse],” said Vidmar. “But that is also the slowest part of the year, and people don’t need as many vegetables then. So we decided to basically only use [the greenhouse] in the summer,” he added.

Neelu Singh, a vegetarian environmental researcher in Longyearbyen, said people back home in India ask how she makes do in the Arctic without eating meat. “I just laugh and say you can get everything there except a few specific vegetables [to cook with],” she said.

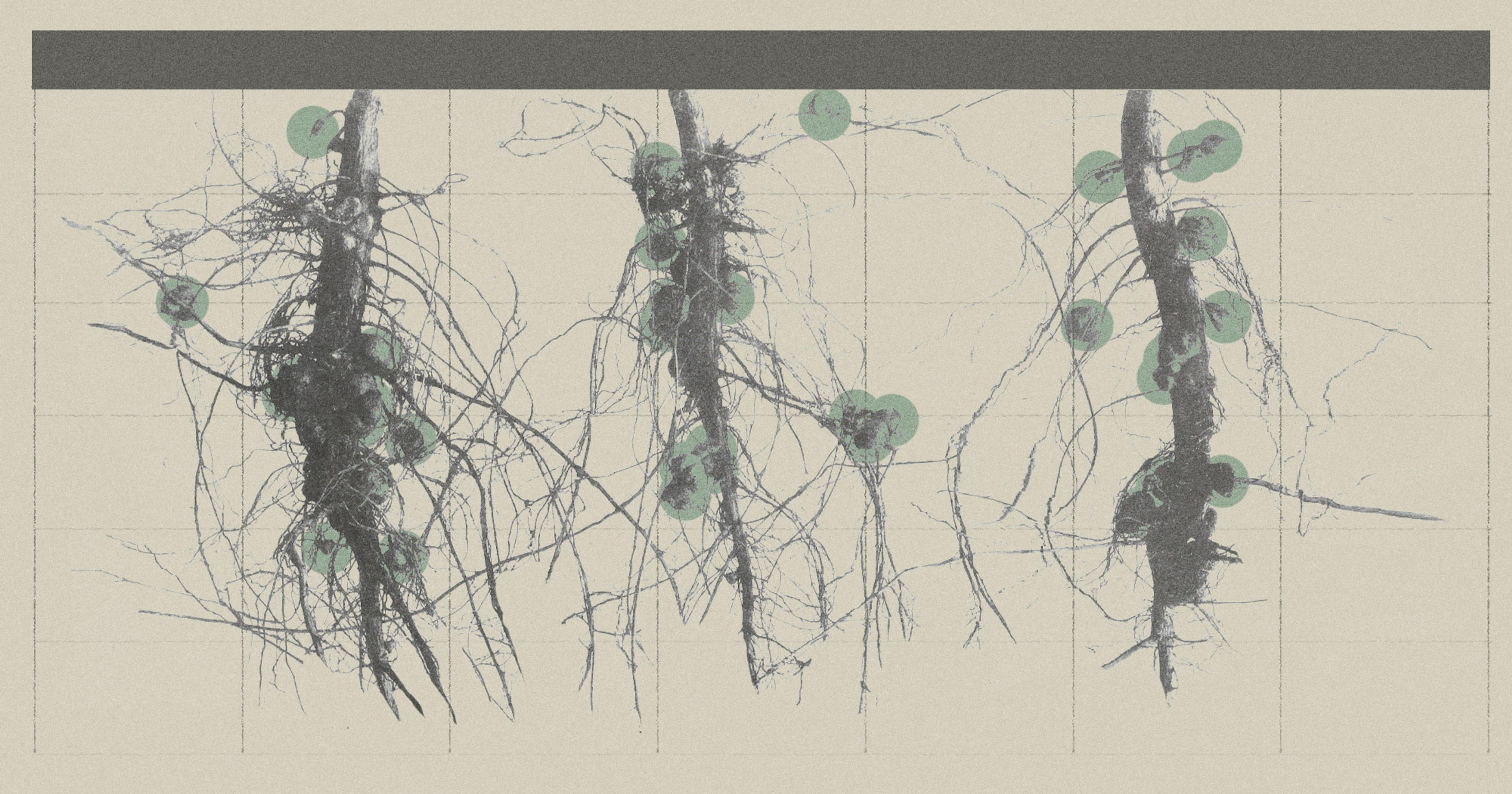

At its peak, Vidmar’s company was producing about 15 to 20 trays of microgreens per week, along with a mix of other vegetables — to be supplied to local restaurants and the town’s only supermarket.

Prior to Vidmar’s bold initiative, there were practically no documented attempts to grow food on Svalbard. While the harsh climate and soil conditions play some role in this, the transient nature of the community and the lack of a business incentive were also major contributors.

“Weather conditions on Svalbard are not conducive to large-scale agriculture. Historically the North depended on hunting and gathering and raising livestock for its food (for instance, reindeer farming in Lapland),” said Adrian Unc, a Polar agriculture expert based in northeastern Canada.

“Agriculture on small, protected plots is not culturally local but rather an activity brought here by the southern colonists,” he added. Accelerated warming of the poles has now made the area more conducive to farming than it was decades ago.

Carbon Footprint Reduction and Financial Viability

Polar Permaculture tries to be as zero-waste as possible, composting their own food scraps, and collecting waste from restaurants to compost; before Vidmar’s initiative, waste on Longyearbyen used to be piped into the sea, or exported to Sweden or Norway.

“Everything was shipped here at a huge premium, and then all of the solid waste was shipped back to Norway and they processed it on the mainland,” said Vidmar.

The carbon footprint of importing food and other essentials to Longyearben is significant; moreover, much of the food rots before it can be consumed and has to be thrown away. Logistical challenges in transporting goods to a region with few flights, and delays caused by unexpected events such as the Covid-19 pandemic, mean that the food supply chain is inherently unreliable on Svalbard.

“If I could grow food in one of the most challenging and remote locations in the world, I can do it anywhere.”

Growing produce locally uses 32% less energy than importing vegetables in the winter, and 50% more in the summer (according to a local feasibility study), but also uses up waste as compost. This waste would otherwise have to be imported, another significant wastage of energy.

“Removing, or lowering the amount of imported food also lowers the pressure on southern food systems, a benefit to all. Agriculture based on improvement of marginal soils is key to carbon-smart northern agriculture,” said Unc.

He added that the use of locally grown and adapted crops is essential to keeping this method sustainable. “Growing local plants is only one step removed from harvesting wild produce.”

Climate Change and Growing Food in the Arctic

The world warming by 0.18 degrees Celsius a decade (and the Arctic warming two to four times faster) has made agriculture possible in many places it wasn’t before. “Global warming will increase the size and abundance of agriculturally favorable pockets, by both increasing the average temperature and increase the length of the season,” said Unc.

He added that “a slow creep of the northern edge of the current agricultural regions” has been noted, especially in central Canada and Siberia.

“We all felt [climate change] there — but for a farmer that’s a good thing,” said Vidmar. “And that’s why many people around the Arctic are now starting to grow their own food — I’ve noticed this in Alaska, the Arctic regions of Canada and Greenland and Russia. That’s kind of what inspired me.”

In addition to growing and selling produce, the majority of Polar Permaculture’s business came from the food experiences and bus tours they conducted, where tourists were served meals made with produce fresh from the greenhouse. But during Covid-19 lockdowns, a drop in tourism and a lack of support by the local administration, which only helped Norwegian-owned businesses get back on their feet, Polar Permaculture had to shut down operations indefinitely.

However, Vidmar’s initiative continues to benefit the town of Longyearbyen in many ways. Inspired by Ben’s zero-waste approach to composting, the Longyearbyen government initiated a campaign trying to make a circular economy, the local airport is now trying to create biogas out of waste, and a local brewery in Longyearbyen is trying to grow produce in a similar fashion.

“My objective now is to use my experience and what I learned there and help set up projects in other places,” said Vidmar. “If I could [grow food] in one of the most challenging and remote locations in the world, I can do it anywhere.”