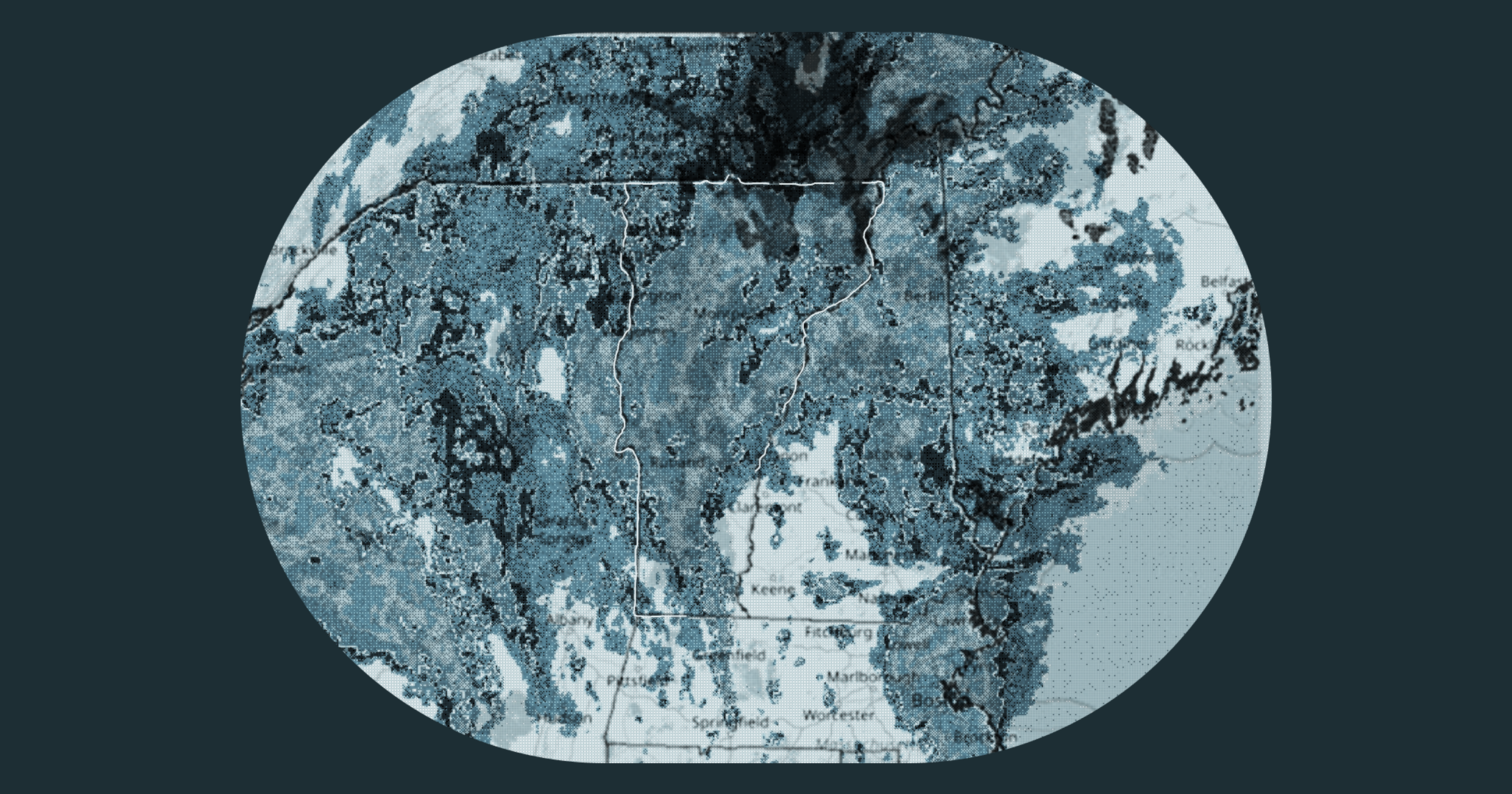

Before Vermont’s devastating July floods there was drought, flash freeze, and wildfire smoke, leaving farmers to ponder what resilience is possible in the face of chaos.

Three weeks after the Great Vermont Flood of 2023 dumped nine inches of rain in 48 hours on parts of the state, Rachel and Jim Bigelow stood under the eaves of their farmstand shed and watched black clouds muscle in between green hills. Rachel had just pointed out the lettuces she’d replanted to replace a sodden crop lost to those earlier storms; Jim wondered aloud whether the ground was finally sufficiently dry to cut his overgrown alfalfa, clover, and timothy for hay. Seconds later, the clouds loosed a new torrent of rain over already-soggy fields. This summer, “It just feels like you’re doing twice as much work to get half as much crop,” Rachel Bigelow said.

July’s disastrous and unprecedented rains caused an estimated $12 million worth of damage to the agriculture sector in Vermont — a state thought to be relatively protected from the intensifying effects of climate change. But listening to local farmers rattle off a litany of challenges besides rain (after the hottest month ever recorded on Earth, no less), it’s obvious agriculture here is vulnerable. Vermont farmers know they need to bolster their operations. But unpredictable weather makes for planning uncertainty. How do you prepare for the possibility of everything?

On the Bigelows’ 190 White River-abutting acres in South Royalton, Rachel reported her most difficult year growing vegetables and flowers. “Early on in the season, it was really, really [hot and] dry so there was very uneven germination,” she said. This, on top of previous years’ dry conditions, had been serious enough that she’d considered installing irrigation. But after an unusual late-May frost that necessitated covering plants in an unheated hoop house with frost blankets, came “lots of rain,” Rachel said. “You can’t really get in there with the tractor to cultivate when it’s so wet, so there’s horrible weeds. Now that the soil’s so wet, it’s just like cement. And there hasn’t been that much sun, so things aren’t growing well.”

Another component to the low-sun equation: smoke drifting in from wildfires in Canada, the particulate matter from which means “there’s nothing [for plants] to photosynthesize,” said state representative David Durfee, a Democrat and chair of the state’s House Committee on Agriculture, Food Resiliency, and Forestry. There’s “an enormous scope of potential issues that we’re still trying to wrap our heads around.”

Still, the Bigelows consider themselves lucky this year. They have some remaining produce, chicken, and duck eggs, beef raised by Jim and his brother, and value-added products like rhubarb chutney to sell to a steady stream of farmstand customers. And they have 10 CSA customers who won’t complain about boxes overstuffed with one surplus veg or under-representing some seasonal favorite. This is in contrast to other area farmers whose acreage was completely submerged by river waters, who experienced such extensive crop loss and damage that they have little or nothing to sell.

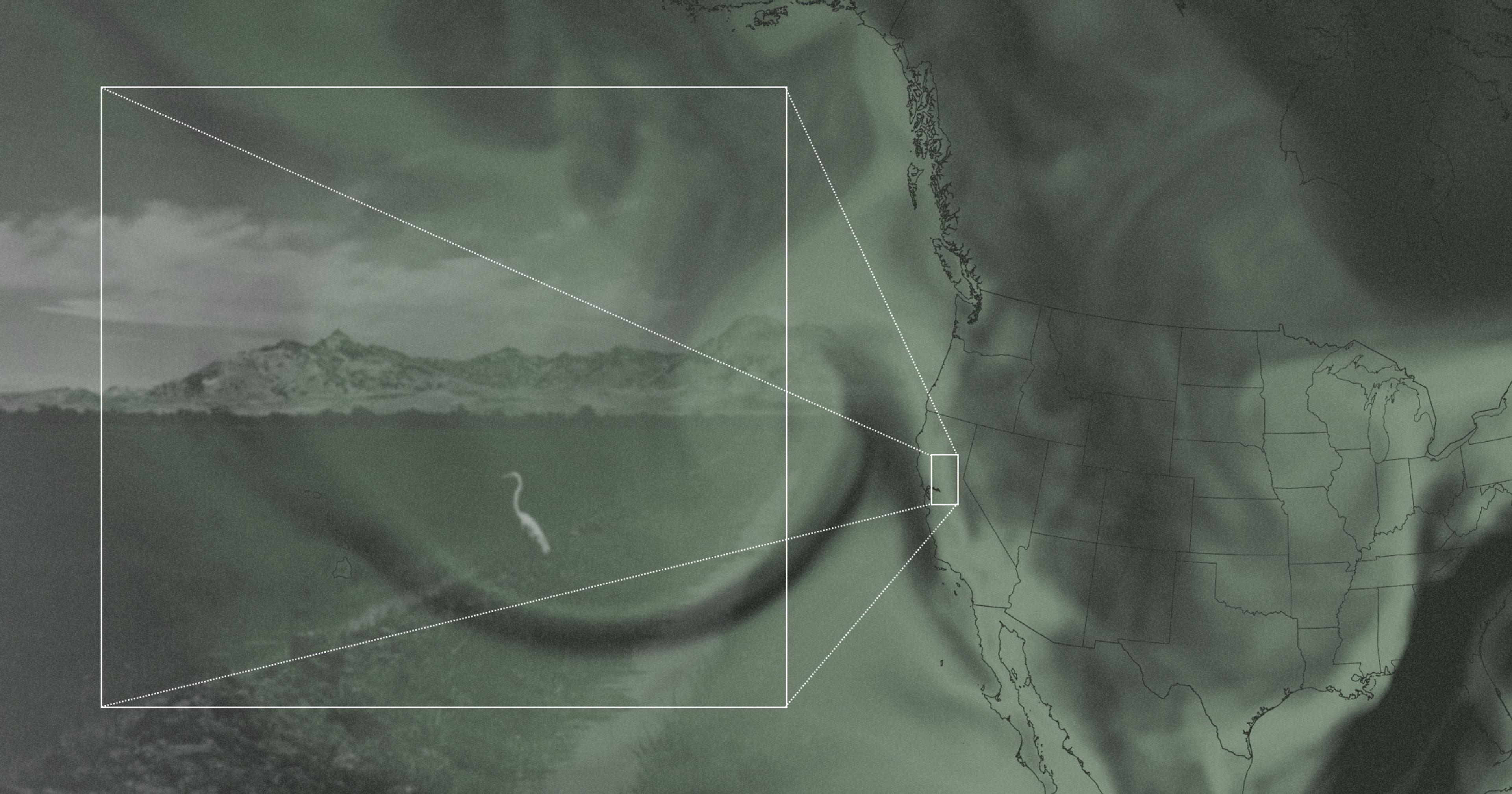

Floodwaters from the Winooski River rose in the Intervale — an 870-acre fertile floodplain in Burlington — higher in late July than they ever have in the past. That includes back in 2011 when Hurricane Irene hit, according to David Zuckerman, Vermont’s lieutenant governor who just so happens to be a diversified organic crop farmer.

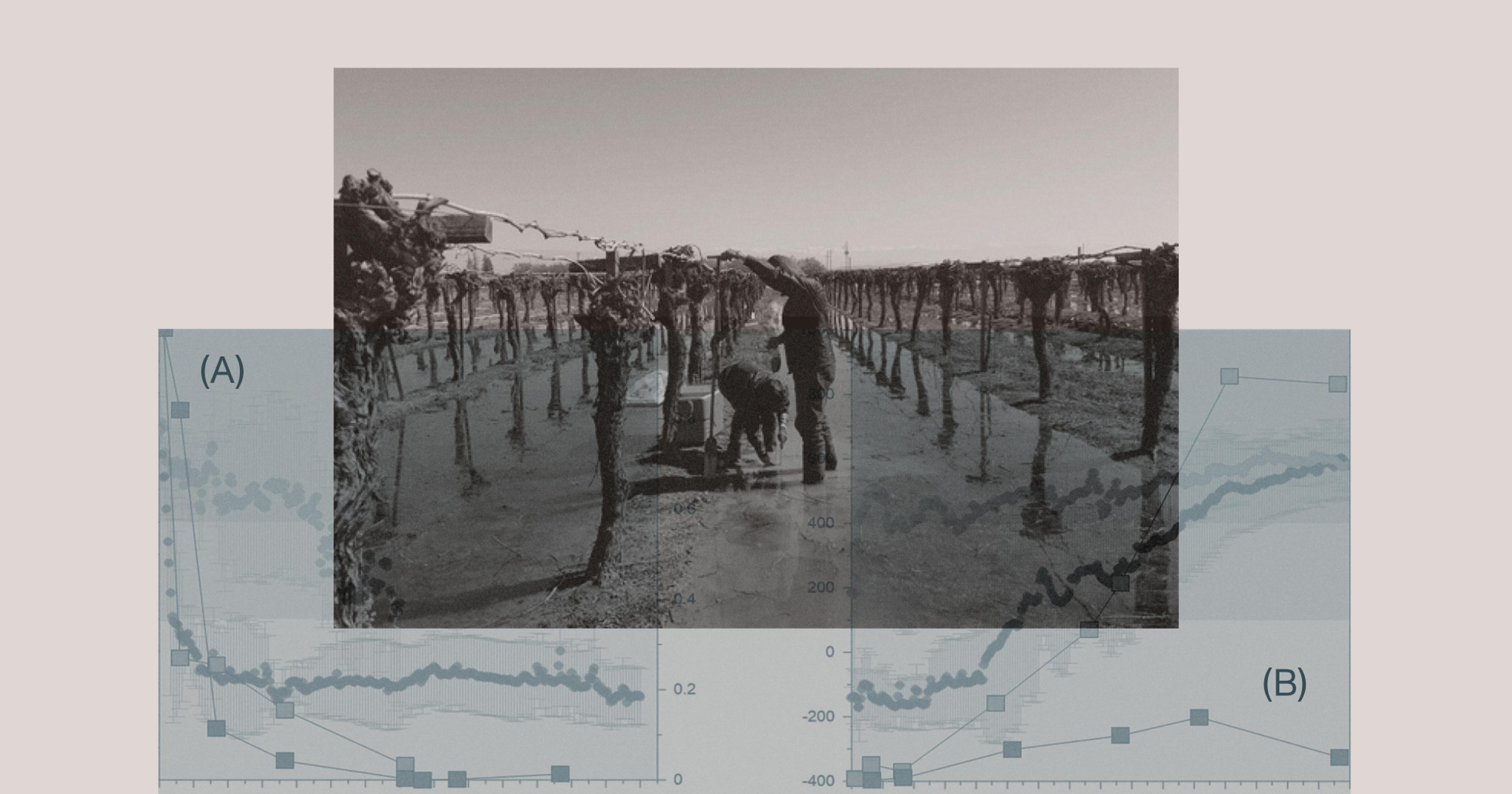

Federal law stipulates that crops that have come in contact with floodwaters, which might be contaminated with pesticides and/or bacteria from livestock operations and sewers, are unfit for human or animal consumption — an increasing problem in California and elsewhere across the country. River-flooded farmland requires a resting period of at least 30 days so that bacteria in the soil have a chance to die off. (Although health concerns around crops that have experienced flooding also include contamination from metals and toxic chemicals, “which actually linger longer,” Zuckerman said.)

How do you prepare for the possibility of everything?

What was devastating about the flooding was the timing. It was late enough in the season that “squash are forming on the winter squash vines and sweet potatoes are vining out a lot and … [farmers] were just getting the Walla Walla [onions] out” of the ground, Zuckerman said. “Fall harvests are slightly possible; people are gonna be able to grow some greens, depending on soil [contamination] and where they are in Vermont. But honestly, both ends of the season just got wiped.”

Bill Cavanaugh, farm business advisor at the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA)-VT, said over 200 Vermont farmers had been impacted by weather events. “Sure, there was that acute flooding event in July,” he said in mid-August, “but it really hasn’t stopped raining; it’s absolutely pouring right now.”

The hay Jim Bigelow hadn’t been able to cut and which he sells to “horse people and cattle people … just lays right down [in the field] when it rains hard,” making it susceptible to mold, “so who knows what kind of quality it will be,” he said.

“Some of my farming friends who have heavier soils said they went out to pick what looked like beautiful carrots and an inch below the surface they were mush,” Zuckerman said. “In our fields [in Hinesburg], we’ve never had this kind of problem in our watermelons … as far as diseases and loss of fruit. And we haven’t harvested lettuce or spinach or arugula or any small leafy greens in weeks because in our sandier soil, all the water-soluble nutrients have leached to a much deeper level far out of reach of the roots of the plants, so we have very yellow or terrible-tasting plants.”

Some aid has been made available. The state of Vermont has made a “relatively modest” $1 million available to farmers, “to replace documentable losses of equipment or structures, but not to replace the loss of revenue,” said Durfee. “It’s very easy to imagine that disappearing very quickly and there being much more demand than there is money.” And the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced that it would offer a variety of “flexibilities” to flood-impacted farmers. Although, “It’s a hard process to navigate and one thing we’re seeing now with this crisis is a real lack of crop insurance,” said Cavanaugh. “It doesn’t pay out well at all for small specialty crop producers. If they can get anything at all it’s frequently pennies on the dollar.”

And the question still remains: Even with money to rebuild and rebound, how can farmers protect themselves against future crises? The Bigelows learned some lessons from Irene. “I had applied for a grant for this greenhouse and the location that we put it was weather-related, because [Jim’s] brother wanted us to put it” in a lower field, said Rachel. “That’s where the river had flooded during Irene.”

“To feed everyone … we need to shift our mindset on how and where we grow our food. And we’ve got to have that conversation immediately.”

“Farmers are really looking for technical expertise in overall land management — thinking through how to irrigate [when it’s dry] or how to design systems,” said Cavanaugh. “We’re really lucky up here, we’ve got really good technical experts [from the University of Vermont and through NRCS] in those realms, but not enough of those people to go around to consult on bigger issues.”

Cavanaugh said NOFA-VT had been concentrating its efforts on offering up to $2,500 resilience grants. He said a lot of grants went toward building community farmstands, to help with food access when town groceries get flooded out but farms are still generating food. This year’s grants also awarded money for building high tunnels and hoop houses to protect against extreme weather events; adding rotational grazing to improve soil fertility; adding a permaculture corridor on land not suitable for crops; and generally diversifying the types of crops grown.

Other than that, “There’s been a lot of talk about water, both getting more of it and getting rid of too much of it,“ Cavanaugh said. ”A lot of folks are having to dig new wells or dig deeper on existing wells, because prior to this year, every year [for] the last few years we’ve had a drought. Then some farms have been putting in drainage ditches and swales to stay ahead of water events“ like this year’s. One farmer, he said, got a resiliency grant a few years back “just to do landscape shaping to try to avoid flooding; it sounds like it worked perfectly in this event.”

Landscaping is on Zuckerman’s mind, too. “With our rolling hills, how can we grow in a more terraced way?” he asked. “It’s a way of managing water flow so you can grow on moderate hillsides without having it all washed away with a heavy downpour, which we’re expecting more of as climate change happens.” He also mused over ideas like vertical and indoor farming as possible future strategies; the possibility of extending the growing season due to warmer winters; and relocation efforts.

“The larger mitigation question is not only for farmers, but for anyone in low lying areas, where we see a lot of lower-valued properties like manufactured homes,” Zuckerman said. After Irene, Vermont bought some of those out and relocated them, restoring the land beneath to floodplain. Irene was also one of the first times the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) “got pushed to reimburse states for, not just replacing what was there, but rebuilding to be more resilient. We built a lot of culverts larger, built a lot of bridge abutments wider, to allow the water to not get blocked up … and flood. Vermont is looking to do more of that now. But to feed everyone … we need to shift our mindset on how and where we grow our food. And we’ve got to have that conversation immediately.”